English professor and member of the faculty senate Elaine Hadley remembers a meeting when the University of Chicago’s faculty governing body was tasked with selecting fonts for the school’s letterhead. Those were simpler times.

These days, the faculty senate is in the thick of a complicated debate as it tries to decide how and when disruptive conduct will be punished at the University of Chicago. The upper administration in Levi Hall is eager for the University to establish a disciplinary system that could be used to sanction individuals who engage in speaker silencing, obstructive protest, and the like. It can't create that system unilaterally, however, because the University’s statutes give the faculty senate jurisdiction to create rules pertaining to discipline for disruption.

The senate is nearing a May vote on a measure that would create a disciplinary system to respond to incidents of disruptive conduct. Levi Hall is now adding pressure by indicating to the senate that if the vote fails, the administration will instead revive a convoluted disciplinary system for disruptive conduct that hasn’t been invoked since 1974. This is according to several members of the faculty senate. A spokesperson said he would prefer not to speculate on what would happen in this scenario.

It is an ultimatum of sorts.

The Maroon spoke to a half-dozen senate members for this story—none of them were excited about the possibility of this outcome. Even the Provost’s office has indicated that it thinks the 1970s system, the “All-University Disciplinary System,” is flawed.

Last June, the Provost initiated this senate debate by charging a faculty committee to produce a report on how to “revise or replace the disciplinary procedures and standards set forth in the All-University Disciplinary System,” which “has seen little use due in part to cumbersome procedures.”

That committee issued its report last month, with Appendix V attached. Appendix V is a proposed new disciplinary system for disruptive conduct, which is what’s now moving through the faculty senate. The man who chaired the committee, Law School professor Randal Picker, is also the spokesperson for a seven person sub-committee of the faculty senate that meets more regularly. That makes Picker the highest-ranking professor in faculty governance.

Picker does not claim to be the leading expert on the University’s statutes (though he says he now has them saved on his iPad). But he thinks it is somewhat unusual that the statutes give the faculty senate the power to create this disciplinary system. The senate generally does not have jurisdiction over other areas of discipline. In fact, it’s relatively uncommon that the senate votes on any matter of University policy.

For those reasons, this is all very unfamiliar to the faculty senate. There appears to be a relatively strong consensus among members of the senate that the University ought to respond to disruption in a centralized, uniform manner and that the current disposition in which disruption is handled at the divisional level is unsuitably disjointed.

But the diverse senate body, which is composed of professors selected by most of the faculty at-large, has a range of opinions on how exactly a centralized system should function. Some of the most staunchly opposed members say they’d rather the 1970s system be revived than vote yes on the system that has been put forth in Appendix V, barring substantial revisions.

Hadley, who described herself as a vocal voice of dissent to the report, said she’d prefer the 1970s procedures—even though they’re not “gorgeous”—because she feels the proposed system is too punitive.

History professor Jane Dailey, who served on the Committee that produced the report, dismisses this criticism. “We were charged with writing a disciplinary report, so by definition it was going to be punitive.” The goal, she said, is to avoid the prospect of students being disciplined by setting a clear and consistent line for what behavior will be punished.

The Picker report—as some members of the faculty senate are calling it—invokes the Board of Trustees in addition to the faculty senate because it recommends changes to Statute 21, which defines disruptive conduct, and only the trustees have jurisdiction to amend the statutes. The Board will convene for its quarterly meeting in May.

The committee that drafted the report is currently taking feedback on the system it proposed in Appendix V. The report was presented at the senate’s March 28 meeting. There will be time for discussion at a meeting near the end of the month. On May 23, the Senate will have an up-or-down vote on a potentially amended version of Appendix V.

A vote was at one point slated for April, but the timing was pushed back when a member of the senate requested more time for discussion.

1969–1970

As Hadley indicated, the faculty senate has laid low for much of its history. Most students have probably never heard of the body—officially named “The Council of the University Senate.”

Charles Wegener, who served on the Council from 1964–67, wrote in a 1969 edition of The Maroon: “Month after month would go by in which there was nothing on the agenda other than routine ‘reports’ generally remarkable only by their dullness, and perhaps a few honorary degrees. On occasion it was difficult to believe that a quorum was in fact present. I cannot now recall why I went to the meetings and in fact I simply forgot a few.”

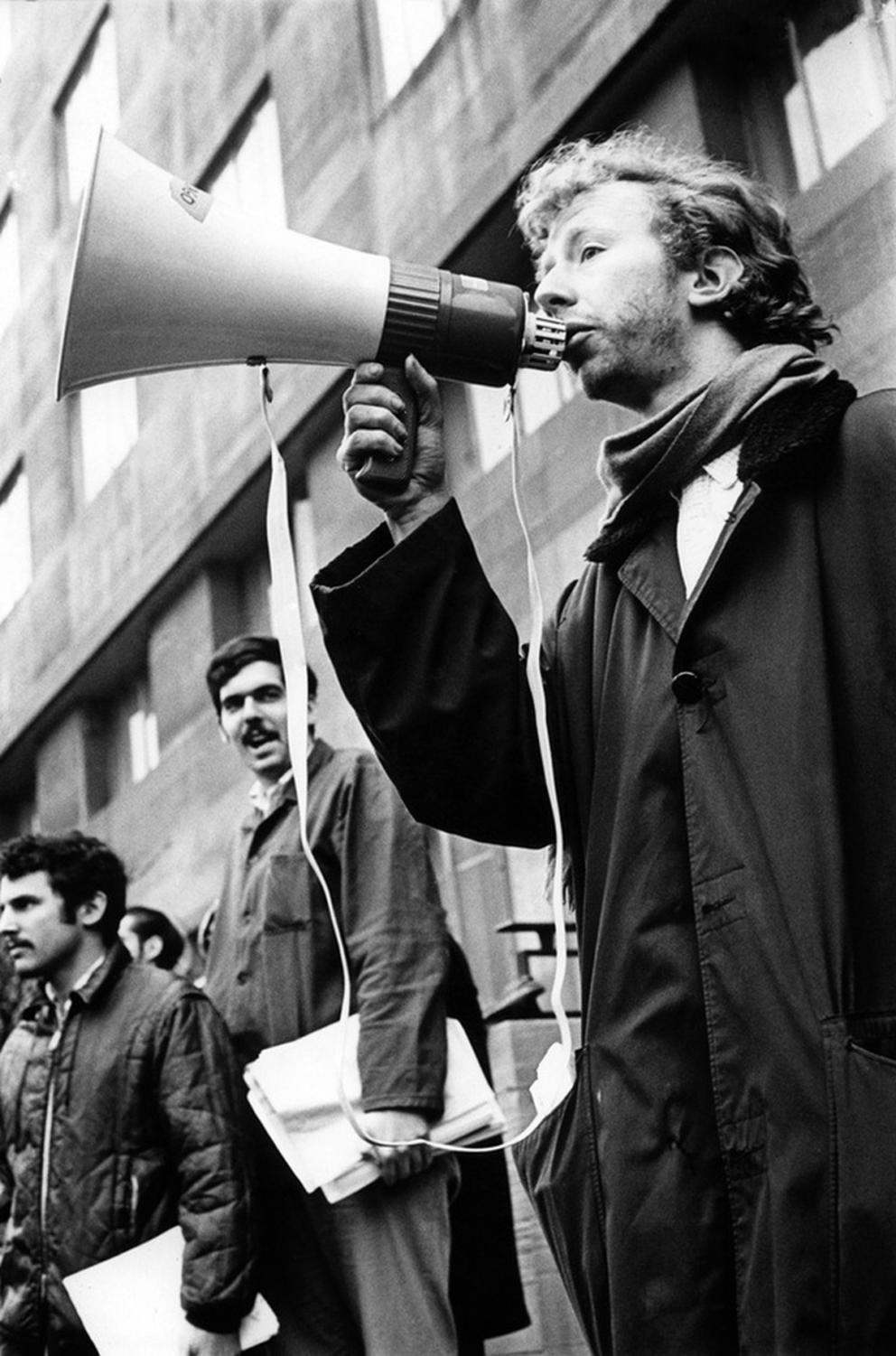

He wrote this reflection amid a highly tumultuous time for the senate in the aftermath of a two-week occupation of Levi Hall by more than 400 students that led to more than 60 expulsions. The process of expelling those students stretched out over months. At one protest of the disciplinary process, a student kicked in the door of the president’s house and pinned a message on the inside. At another, Julian Levi, an urban studies professor and the brother of the University’s president, responded to protesters chanting “sixty-one”—the number of students then facing disciplinary action—by pointing at one protester after another and counting up: “sixty-two,” “sixty-three,” “sixty-four.”

The protests spilled into the deliberations of the disciplinary committees themselves. Within a week of the end of the sit-in, 200 protesters blocked one disciplinary committee in a Law School courtroom for two and a half hours. The stand-off ended when 20 law students and security guards rushed past students guarding the doors, allowing the disciplinary committee to leave through a basement exit.

Call that the worst-case scenario. In the aftermath, the administration thought it would be prudent to get the faculty senate involved to “decentralize” the decision-making process.

The faculty senate sprang into action. It passed resolutions, held regular meetings (which demonstrators tried to protest too), issued statements, created committees, and asked for reports. The majority of the faculty senate ultimately came out in support of the disciplinary actions the University took against the protestors, but it called for a committee to conduct a larger review of the University’s disciplinary response to disruptive conduct.

A few months later, the “Subcommittee on Disciplinary Procedures” had issued its report. It recommended the creation of a new disciplinary system to address disruptive conduct. In May 1970, the faculty senate voted in favor of the disciplinary system. The resolution it passed also recommended a change to the Statutes of the University that, when approved by the Board of Trustees, put jurisdiction over rules regarding discipline for disruptive conduct in the hands of the Senate. The “All-University Disciplinary System” is this system, although it was amended in 1976.

Now, in the wake of much smaller-scale occupations of Levi Hall last year and other incidents of disruptive protests on campus, the faculty senate is again at the center of the debate about disciplinary response.

The charge

Last June, then-Provost Eric Isaacs sent an e-mail officially announcing the creation of the “Faculty Committee on University Discipline for Disruptive Conduct.”

The charge to the committee states, “Given the increase in disruptive conduct at the University as defined by Statute 21, it is important that an improved system be developed and approved.”

The committee was tasked with revising or replacing the 1970s system, addressing the range of disciplinary sanctions for disruptive protest, issuing suggestions for in-the-moment response to speaker disruption, considering how to respond to disruption by non-students, and giving advice for educational programming on free expression.

It was at the request of committee chair Randal Picker that the educational element was included in the Provost’s charge.

“They were focused on creating a disciplinary regime for [disruptive conduct]. I said ‘That’s great, we should do that, but I also want to create an educational regime,” Picker said in an interview last Friday. “Discipline is a small part of what we do; education is a huge part of what we do. So the charge was reformulated to put that into it.”

Asked for clarity on his use of the word “they,” Picker turned to the window in his north-facing office on the sixth floor of the Law School and pointed to the administration building, Levi Hall.

The context

The administration’s charge to the committee referenced an uptick in disruptive behavior last year, but a list of incidents was not included. That meant the committee had to do research.

“We put together a list of what we thought of were situations that might be within the ambit of this that occurred on campus in the past couple years. The truth is the people who were appointed—it is faculty members—we didn’t necessarily know anything about this,” Picker said. “I gotta say—we looked at The Maroon a lot.”

Picker said the committee identified two different types of disruptive situations. The first is “speech-speech” conflict. In this category, he said, is the incident last February when the state’s attorney, Anita Alvarez, was shouted down at the Institute of Politics by Black Lives Matter protesters. Clashes between Israeli-affiliated groups and Students for Justice in Palestine that are common across the country may also fall into this category, he said.

“On the one hand you might say—‘Well, that was free speech by those individuals.’ On the other hand, you had a group of people who had come to hear Alvarez; Alvarez herself wanted to speak; she left; and the group that wanted to hear her couldn’t hear her.”

Picker sees another category of disruptive speech that does not directly interfere with the speech of others, but instead interferes with the activities of the University. Two incidents last year when protesters occupied Levi Hall fall into this category of speech, he said.

“The people taking over the building would say they’re engaging in an act of protest and, in that sense, speech,” he said. “In one situation quite clearly the elevators were blocked and that creates safety hazard issues. So that can’t happen.”

The committee also studied incidents on campus when protesters were able to communicate a message without escalating to disruption. He cited a silent protest last April by members of the Armenian Students Organization.

The committee kept track of protests this year. Picker said he stood out in the cold for an hour in February to observe the protest outside an IOP event with Corey Lewandowski.

Senate member and comparative literature professor Haun Saussy also attended the Lewandowski protest, but as a participant. Saussy, who pointed to a “Fuck white supremacy” sign in his Wieboldt office as he talked about his political ideology and his opposition to the current White House, said that he and other members of the senate are concerned about a more “heavy-handed” response to protest from the University.

The Senate met with dozens of members of the University of Chicago community with a range of ideological views. A list of those people—attached to the report—includes administrators who work closely with discipline, campus police, deans, faculty, and community members. In terms of students, the committee held an open forum in October, and it solicited feedback directly from Student Government leaders, activists, and the president of College Republicans (CR).

Picker and Dailey said the main item of feedback the committee gathered from students was interest in more clarity from the school on what is and what is not punishable disruption.

“While incidents obviously can differ on a case by case basis, it is very important to have a basic set of expectations for all students when we arrive on campus,” third-year CR President Matthew Foldi said.

Student Government President Eric Holmberg also confirmed that this was a “prominent” point expressed by students, but he noted that a range of issues was discussed.

The committee studied the University’s most recent reports on related subjects—the Stone report and the Strauss report—and strengthened its understanding of the various layers of jurisdiction.

Three branches

The Council of the University Senate, the Board of Trustees, and the administration each have jurisdiction to implement parts of the Picker report. The educational and administrative recommendations in the report can be implemented without a vote from the senate or the trustees.

This includes recommendations in the report pertaining to changes to event management intended to reduce speaker silencing. The report calls for deans-on-call trained in responding to disruption and for educational programming by the Office of Campus and Student Life on “the rights and responsibilities of participating in the free-speech commons at the University.”

Statute 21

The Board of Trustees has jurisdiction over proposed revisions to Statute 21. As presented in the report, additions are bolded and deletions are struck-through:

Disruptive conduct is conduct by an individual or by a group of individuals

member of the University communitythat substantially obstructs, impairs, or interferes with: (i) teaching, study, research, or administration of the University, including UCMC’s clinical mission; (ii) the authorized and other permissible use of University facilities, including meetings of University students, faculty, staff, administrators and/or guests; or (iii) the rights and privileges of other members of the University community. Substantiality may be judged based on a single incident or on an aggregation across incidents. Anyonemember of the University communitywho engages in disruptive conduct, whether individually or as part of a group, will be subject to disciplinary action. Disruptive conduct includes but is not limited to: (1) obstruction, impairment, or interference with University-sponsored or -authorized activities or facilities in a manner that is likely to or does deprive others of the benefit or enjoyment of the activity or facility and (2) use or threatened use of force against any member of the University community or his or her family that substantially and directly bears upon the member’s functions within the University.

The faculty senate could potentially vote on whether to recommend the Statute 21 revisions to the trustees. It was unclear to several members of the senate—Picker included—if that would definitely happen.

Vice President and Secretary of the University Darren Reisberg has been helping the senate navigate procedural questions. Reisberg directed a request for comment to the University’s press office. The University issued a general statement in response to The Maroon’s request for comment, but had no comment on the process in the senate because it is ongoing.

A biology professor on the faculty senate, Erin Adams, said that a recommendation from the majority of the faculty senate could carry a lot of weight with the Board of Trustees, even though it would not be binding. Adams, who is a member of the seven person sub-committee, believes it’s critical that protesters do not obstruct the rights of others to express themselves, and she generally spoke in support of the Picker report.

Other members of the senate raised concerns that the definition of disruptive conduct in Statute 21 encompasses legitimate protest.

Math professor and faculty senate member Denis R. Hirschfeldt pointed to an article about the report by John K. Wilson on the Academe Blog. Wilson criticizes the definition of disruption in Statute 21, and he is skeptical that the proposed revisions will improve it.

“Any rule that says ‘includes but is not limited to’ is completely unlimited. The University can literally say that anything is disruptive conduct,” he writes. “And it definitely should not be defined to include ‘enjoyment of the activity or facility.’ … A protest almost always affects the enjoyment people have at an event. It can annoy and inconvenience people. But being annoying shouldn’t be punishable behavior.”

Picker, however, says that the committee was not tasked with reinventing Statute 21. “You’re given a point, and you should stay in the neighborhood of that,” he said regarding the charge from the administration.

Though he did not write it, Picker defended parts of the language in the statute and contested some of the criticisms in Wilson’s blog post. “There was a definition of disruptive conduct there. The first part of Statute 21 is that definition.” Picker added that ‘included but is not limited to’ is common language in law and contracts.

Hirschfeldt raised another point that Wilson’s blog makes about the new sentence in Statute 21 regarding aggregation of repeat incidents. “If a single incident does not justify punishment, then repetition of it at different events should not be punished,” Wilson wrote.

Picker did not entirely dismiss this argument. “We’re hearing feedback; we’re going to iterate. And maybe we’ll say, ‘Oh, that didn’t work.’”

Wilson also blasted the proposed revision to include the word “group” in the statute. He argued that it seems to open up the possibility that a member of a group could be disciplined for group behavior even if the individual did nothing wrong. Picker said that is not the intent behind this proposed language revision. He said the intent is to reflect the reality that oftentimes disruption is not the act of a single individual, citing the incident at Berkeley this year.

Inside the senate debate

Section 12.5.3.5 of the University’s statutes gives the faculty senate jurisdiction to determine the University’s rules pertaining to Statute 21. That means the senate is responsible for figuring out how the principles in Statute 21 are enforced in practice.

After the massive sit-ins at the University of Chicago in the late 1960s, the faculty senate instituted in 1970 the All-University Disciplinary System for disruptive behavior.

At the start of each fall quarter, the president of the University was to appoint five faculty members to a standing “University Disciplinary Committee.” A panel of 15 students (five undergrads and 10 graduate students) was to be appointed by Student Government and the graduate school student bodies. From this pool of students, two would be selected to join the standing faculty committee to hear a particular case.

The accused individuals could choose if the hearings were conducted in public or in private and they could call witnesses to testify or submit written statements. Notably, the disciplinary committee “ignores any previous history of disciplinary action with respect to the student charged.”

Possible sanctions include disciplinary probation, suspension, and expulsion.

Picker confirmed what senate faculty member Na’ama Rokem first told The Maroon—that the administration will use the 1970s procedures if the senate does not pass a version of what’s proposed in the Picker report. Asked what happens if the measure fails, Picker said, “Well, the answer to that—according to the University—is the 1970s procedures will be applied on a going-forward basis.”

Picker said that’s not necessarily a nightmare scenario, but it’s not ideal, either.

“The thing that I think one should be concerned about about the 1970 procedures [is] there seems to be no statutory or rule-based path for an informal resolution. Once you sort of get on the train, I think the train runs forward. I don’t think that’s good. I think you want to have the chance to make an assessment, and then say ‘OK, we don’t have to go through a full blown hearing.’ And I think there’s a concern that the disciplinary results aren’t as flexible as you’d like.”

In addition to suspension and expulsion, the Picker system would equip disciplinary committees with a range of lesser sanctions: warnings on students’ educational records, probation status that would have to be considered if a student were to be summoned to another hearing during the probation period, loss of certain University privileges, and discretionary sanctions that “may require the completion of additional academic work, community service, or restitution/fines by a given deadline.”

Section IV of Appendix V outlines an informal complaint resolution process that would give the Associate Dean of Students in the University for Disciplinary Affairs the ability to resolve alleged violations of Statute 21 without a hearing. The respondent would be able to accept the informal resolution or request a hearing by a committee.

There are a number of other substantial differences between the procedures in the Picker report and the 1970s procedures. Under Appendix V, disciplinary committees would be composed of three faculty members, one staff member, and one student. The report says that the committee will be drawn from a larger pool of individuals appointed by the Provost. Appendix V, however, does not say who will select these people.

Several members of the faculty senate object to a system in which the administration is responsible for appointing the members of disciplinary committees. Hadley said she worries that a future administration could use appointment power to “stack the committee.” Hirschfeldt raised the concern of partiality in the case of a protest that is directed at, for example, a trustee.

Presented with this criticism, Picker seemed open to revision. “We should think about that. Certainly our intention was not to stack the deck.… It sounds like we need to fix that. I don’t know what that fix looks like exactly. I’ve heard the idea of a vote suggested. That’s a pretty cumbersome mechanism, but it sounds like we need more clarity there.”

Picker did not totally dismiss the viability of a random, jury-style selection process. “I don’t know if that’s crazy—not at all,” he said. “My understanding, unsurprisingly, is that actually getting people to do this turns out to be hard. That’s true in sexual misconduct [proceedings], it’s true in other disciplinary proceedings, as I understand it.”

After the 1969 sit-in, the idea of random selection was considered. Noting the technological difficulties of creating a random system for selecting disciplinary committee members, Harry V. Roberts, a University statistician wrote, “In principle, [randomization] might be achieved by mechanical mixing or other gambling-type devices, by use of published tables or random numbers, or by use of computer procedures for generation of psuedo-random numbers.”

Roberts, whose paper advocated for randomization to prevent the administration from “load[ing] the dice,” acknowledged that randomization was unlikely to be adopted. “In candor I must report that I am reasonably confident that the proposal will not be adopted by the University of Chicago,” he writes. “Many feel, for example, that only people with a certain combination of sensitivity, judicial temperament, tough-mindedness, compassion, coolness under fire, and the like, should be considered for a job that is arduous, frustrating, and even hazardous.”

Picker’s committee modeled much of its Appendix V system after the University’s disciplinary system for sexual misconduct. A couple of faculty senate members were confused as to why the committee chose to do so. Hirschfeldt noted that there is a very high degree of confidentiality in the Picker system as both disciplinary proceedings and disciplinary outcomes are to remain confidential.

Appendix V reads: “All parties and witnesses involved in an investigation or proceeding under this disciplinary system are prohibited from disclosing, at any time and through any medium (including social media), the identity of the parties and witnesses, and any details or information regarding an incident, investigation, or proceeding.” Although there are some exceptions to this rule, in this respect, Appendix V is in stark contrast to the 1970s procedures which allow for public hearings.

Picker said that the committee looked toward the sexual misconduct disciplinary system as a starting point because it is the most recent University disciplinary system: “You try not to reinvent the wheel.” And, because that system has seen use, he said the committee could get “a sense of what is working and what is not working.”

Picker said that his aim with regard to confidentiality was to create the least burdensome rules possible “consistent with FERPA and consistent with proceedings that actually work.” FERPA is a federal privacy law pertaining to educational records. Although there are confidentiality rules in the University-wide Disciplinary System, Appendix V is even stricter. For example, participants in sexual misconduct proceedings can share the outcomes of hearings and facts about incidents that they knew prior to the proceedings—Appendix V does not have these exceptions.

The confidentiality rules that go beyond FERPA are intended to make the hearings function smoothly, he said. “Try this—if someone was livestreaming a hearing, would that work? I doubt it.”

This all may seem technical, but confidentiality rules could matter, for example, in the case of a leader of a sit-in wants to tell his story to the New York Times.

Other points of debate in the senate concern the role lawyers should be allowed to play in the hearings and whether accused students should be able to call witnesses—as the the 1970s procedures provide—or merely “suggest” witnesses be called, as Appendix V proposes.

Unlike the 1970s procedure which ignore student’s previous disciplinary records, Appendix V has a procedure for a dean to notify disciplinary committee’s of prior Statute 21 violation allegations against the student in question.

Anyone can initiate a complaint under the Picker system, which diverges somewhat from the 1970s procedures which leave more of this responsibility to deans. “In SJP-Israeli conflicts, I could see either side doing that,” Picker said. “In the IOP situations, maybe it would be IOP.” It could also be the administration, and he stressed that deans would be able to initiate complaints.

The “logical or illogical conclusion”

All this comes at a time when the president of the University of Chicago Robert J. Zimmer is making a stir by weighing in on the national dialogue on how colleges should respond when campus groups invite provocative speakers like Milo Yiannopoulos, Charles Murray, and Richard Spencer.

Zimmer’s position, which is bolstered by the Picker report, is that campus groups should be allowed to invite anyone to speak to them. This means the administration plays no role in approving speakers, and it means that the University of Chicago thinks members of the University community and people outside that community should not be able to prevent those people from speaking—exercising what is sometimes called a heckler’s veto.

The corollary to that is the possibility for a scenario in which a deeply controversial speaker comes to campus and the University is responsible for shielding that speaker from disruptive protest, even if the speaker is spreading a message that is antithetical to the mission or values of the University.

Picker said it’s the best of bad options. “I’ll say ‘yes.’ This is one of these things where you announce some principles, and then you take them to their logical or illogical conclusion, and that’s I think where you end up,” he said. “I don’t want Richard Spencer on campus. I’ve watched him on YouTube for two minutes. I’ve seen enough. I don’t need more. But if someone invites him to campus, we’re stuck.”

After talking about how much time the committee has spent on the report, and how sometimes he’ll sit back in his chair to stare at the ceiling to brainstorm ideas, and how he’s had to wrestle with and try to make sense of feedback from a community member who invoked a Foucauldian opposition to discipline for protest, Picker mused about how hard the debate is and how the country has struggled over time to get it right.

“We’re wrestling intensely with this on university campuses,” he said. “And wow—if we can’t get this right, who can?”