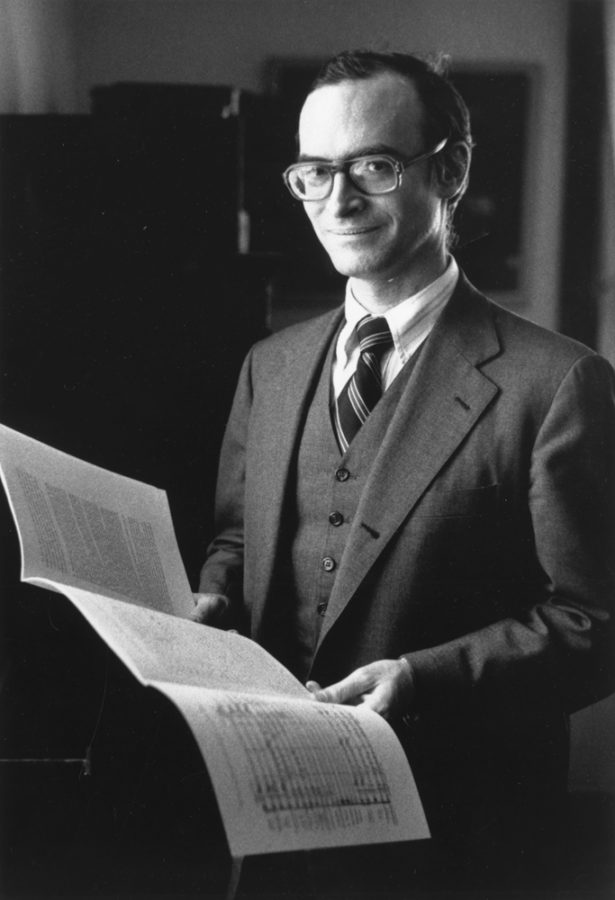

On June 13, Philip Gossett, former dean of the humanities (1989–99) and Robert W. Reneker distinguished service professor emeritus, passed away at his home in Hyde Park at the age of 75 after a lengthy battle with progressive supranuclear palsy.

Gossett was known on campus as a passionate, opinionated, and energetic scholar in the Department of Music, where he taught from 1968–2010. During his stint as dean, he oversaw the foundation of the Franke Institute for the Humanities, as well as the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality.

Beyond the quad, Gossett was internationally revered as an authority on 19th-century Italian opera. His pioneering research on the operas of Rossini and Verdi transformed the field, and he spearheaded the editing and compilation of the first critical editions of the composers’ complete works. Editorial work on the Rossini edition remains centered at the Centro Italo-Americano per l’Opera (CIAO), or the Center for Italian Opera Studies, on 5720 South Woodlawn Avenue, which opened in 2006.

An unlikely path

Gossett was born on September 27, 1941, in New York City. According to the preface to his Laing Prize–winning book, Divas and Scholars: Performing Italian Opera, his zeal for opera can be traced back to weekly Metropolitan Opera broadcasts—to which he sang along “with gusto”—and dedicated attendance at Saturday performances, usually in the standing-room section.

He matriculated at Amherst College in 1958, lugging a reel-to-reel tape recorder to his freshman dorm. Gossett initially studied math and physics, but graduated summa cum laude in 1963 with a degree in music.

Later, as a graduate student at Princeton University, his decision to write his dissertation on Rossini raised eyebrows. Italian opera, especially bel canto, was considered beyond the realm of “serious” study. Save for a handful of “revised and corrected” editions, 19th-century Italian opera had been denied the same scholarly rigor afforded to the Austro-German repertoire.

Gossett confronted these gaping holes firsthand during his Fulbright research in Paris. He found that over time, each performance of Rossini’s operas inevitably spawned new versions with tweaks and inserted pyrotechnics, making it almost impossible to pin down an “original” version.

Filling this void would become Gossett’s work of thirty years and his lifelong raison d’etre. After completing his foundational dissertation “The Operas of Rossini: Problems of Textual Criticism in Nineteenth Century Opera,” he went on to become general editor of the Works of Giuseppe Verdi and the Works of Gioachino Rossini. For his research, Gossett was awarded the Italian government’s highest civilian honor, the Cavaliere di Gran Croce, in 1998. At home, Gossett won numerous accolades from the American Musicological Society (AMS), which he led as president from 1994–1996. He was also the first musicologist to receive the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s Distinguished Achievement Award.

From the ivory tower to the opera house

But Gossett was not content to rest on his academic laurels. Contrary to the University of Chicago’s famous quip that theory trumps practice, he viewed his scholarship as symbiotic with the stage. Over the years, he worked with the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Teatro alla Scala, and Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, among others, and collaborated with the likes of Renée Fleming, Cecilia Bartoli, Joyce DiDonato, Samuel Ramey, Juan Diego Flórez, and Marilyn Horne.

Riccardo Muti—currently music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) and a staunch advocate for como è scritto (“as written”) performance—regularly collaborated with Gossett, singling him out in the audience for praise in a 2015 visit to campus.

During his talk, Muti referenced an example from the last act of Rigoletto which underscored the importance of a well-researched critical edition. In the commonly-used version of the scene, the Duke of Mantua enters a tavern and asks for “una stanza, e del vino” (“a room and some wine”), cuing Rigoletto, inexplicably, to grumble about the Duke’s foul habits.

“It didn’t make any sense,” Muti said.

Gossett and his team, however, found out censors had edited out the original line: “tua sorella, e del vino”—”your sister and some wine.”

“Finally, I could sleep at night doing Rigoletto,” Muti joked.

Muti repeated the anecdote in an obituary for Gossett which ran in The New York Times, adding that the critical editions were “a blessing for the conductors that wanted, really, to bring back a certain dignity to the scores, to bring back the original ideas of the composers.” Last month, he dedicated the CSO’s final subscription concerts of the season—coincidentally, of Italian opera masterworks—to Gossett’s memory.

Other luminaries echoed the profundity of Gossett’s loss, including Anthony Freud, general director of Lyric Opera of Chicago.

“All of us at Lyric and throughout the opera world are deeply saddened by the news of Phillip Gossett's death,” Freud wrote in a statement to The Maroon. “Throughout his distinguished career, Phillip brought many neglected works to light while also bringing new insights to pieces we thought we knew well…. All of us who had the privilege of knowing him and learning from him have been given a great and lasting gift.”

Addio, del passato

Gossett’s death was announced to the music department via email by Anne Walters Robertson, Claire Dux Swift distinguished service professor of music and current dean of the Humanities.

“Philip was a generous, gregarious, vociferous, and highly supportive dean, known for writing penetrating notes to colleagues about their most recent books and for going toe to toe with the administration,” she wrote.

Faculty members in the department echoed Robertson’s summation. Martha Feldman, Mabel Greene Myers professor in the department of music and current AMS president, remembered Gossett as “the most conscientious and energetic colleague one could possibly imagine.”

“As [Humanities] dean, he was legendary for reading all the new books published by faculty from every department. Not only did he digest them cover to cover, he dashed off letters about them to each and every author,” Feldman wrote to The Maroon.

Many remembrances of Gossett mention his responsiveness to queries large and small. Beth Parker, a vocal coach at Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts and CIAO coordinator from 2011–2015, remembers an artistic director asking her to email Gossett to settle, once and for all, whether fortepiano or harpsichord ought to be used to accompany recitatives for a Mozart opera. “I will believe whatever that man tells me,” the director declared.

“Within 15 minutes I received a most gentlemanly and courteous answer that…the last harpsichords were made in Italy in 1811, and that certainly the theaters in Mozart’s time were no longer using them in the 1780s,” Parker said.

Later, while attending a lecture in Chicago in 2010, Gossett remembered Parker, and came on board as CIAO Coordinator within a few months.

“Later I learned that many of our editors on both the Rossini and Verdi editions had similar ‘origin stories,’” Parker said. “He had an instinct for drawing people to him who were not only capable scholars, but fine human beings as well.”

In fact, Gossett drew young scholars to Chicago from all over the globe. In an email, Claudio Vellutini (Ph.D.’15), who lived and studied in Italy, said that Gossett was “a decisive reason for me to join the doctoral program in musicology [at the University of Chicago].” He worked with Gossett as both his advisee and research assistant at CIAO.

“We always took pleasure in teasing each other's taste, fully aware that our love for opera was not only a matter of intellect, but also something visceral,” Vellutini wrote. “As he once told me, ‘there is no way you can make a rational argument when you feel something viscerally.’”

Like Vellutini, Miriam Tripaldi, a Ph.D. candidate in the music department, credited Gossett for her decision to pursue a doctorate at the University of Chicago. As Gossett’s last advisee, Tripaldi said the older scholar was “like a father” to her, and she had been planning to surprise him with the news that her double PhD had been approved at the departmental and divisional levels the day after he died.

“He taught me something to the very end: never wait to tell someone about something, because it might be too late otherwise,” she said.

Tripaldi recalled that Gossett always insisted on lecturing with a piano so he could play and sing examples. As his former student Ellen T. Harris (Ph.D. ’76), former AMS president and professor emerita at MIT, wrote in his official obituary, “He regularly would run to the nearest piano and play his own examples from the manuscript scores with verve and great finesse [and sing] with equal verve and less finesse.”

According to Harris, Gossett’s will bequeathed his “complete music collection of more than 2,000 items” to the Juilliard School for use by future researchers and performers.

“People wonder what will befall Italian opera scholarship now that Philip Gossett is gone, but I can tell you that he has trained an army: two generations of scholars and musicians who will continue along the trail he blazed for us,” Parker said.

Though in demand all over the world, as Gossett wrote in Divas and Scholars, there was a reason he chose to remain in Hyde Park, at the University of Chicago.

“Among institutions, the University of Chicago must take pride of place. I… have long felt that no other institution could have offered me such an intellectually stimulating environment in which to grow, nor such tangible and intangible support of my efforts.”

Gossett is survived by his wife Suzanne Gossett, professor emerita of English at Loyola University Chicago, his sons David and Jeffrey, and five granddaughters.

In lieu of flowers, the Gossett family requests that donations be made to the University of Chicago Music Department (5235 South Harper Court) or to a charity of your choice.