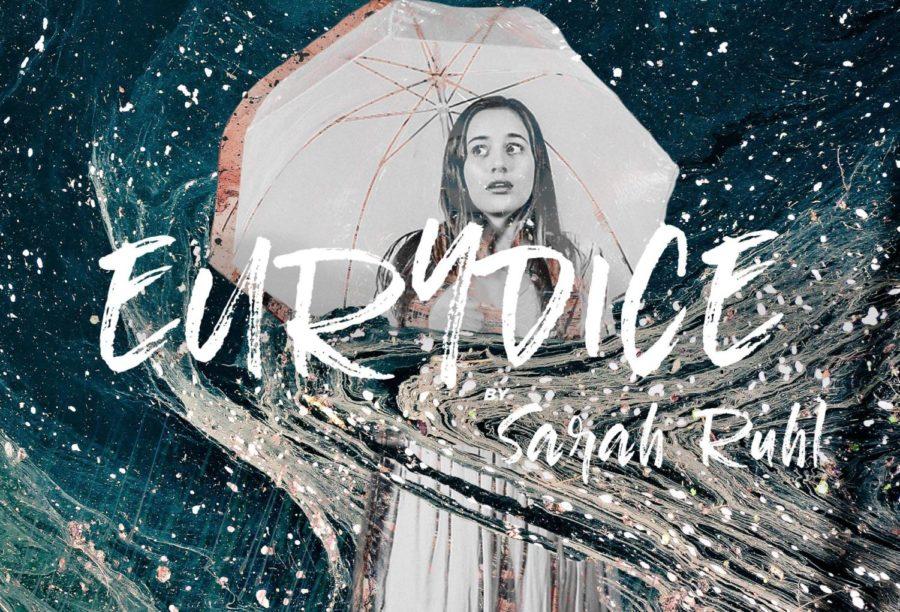

The myth of Orpheus and Eurydice is among the most persisting legacies of Greek antiquity. It has been told and retold by Virgil, Ovid, and even Plato. This time, it finds itself reincarnated in Sarah Ruhl’s 2003 Eurydice, which supplants the myth’s conventional protagonist with his eponymous paramour. The play revels in the power of language to transform people and puncture the thin gossamer veil between life and death. Running from Thursday, February 22 to Saturday, February 24, the University Theater (UT) production of Eurydice was directed by Megan Philippi and played at viewers’ heartstrings with a melody at once delightful and devastating.

The traditional narrative centers around Orpheus: how he loved Eurydice, how he lost her to a viper, how he braved the gates of Hades to retrieve her, and how he fatally turned to look at her as they were leaving towards the living world, breaching the one condition of her liberation and dooming her forever. In Ruhl’s play, Eurydice is granted far more agency and is developed as a real, three-dimensional character as opposed to one of her husband’s instruments. In the final few scenes, it is she who calls out Orpheus’s name, causing him to turn. Additionally, countering Orpheus’s perhaps unhealthy musical obsessions is Eurydice’s own passion: reading. Books and letters are used as plot devices through which Ruhl explores the relationship between language and memory. After dying, Eurydice’s memory is wiped when she is dipped in the River Lethe; her father restores her recollections, in a sense resurrecting her by teaching her how to read and write.

The play is humorous in two senses of the term: With oddball lines and quirky settings, it encourages viewers to laugh at their tragedies, and Ruhl’s presentation of emotion is a medieval, pre-Freudian one of the five humors. Caught in a fervor, it is not always clear why the characters do the things they do–why Eurydice calls Orpheus’s name or why the father consummately wades through the river. That said, Eurydice is not concerned with locating the motivations behind certain actions as much as engaging viewers in a poignant emotional dialogue.

Playing the titular character and her father were second-years Faith Shepherd and Leonardo Ferreira Guilhoto, respectively. Shepherd’s performance is nymph-like: She played Eurydice with a vivacious passion and a zeal for words and stories. However, just as the tide of her zest captivated viewers, so too did its ebb, revealing her deep vulnerability and even naiveté. Ruhl’s Eurydice breaks the ancient mold with her clumsiness and disharmonious singing, and Shepherd does the role justice, acting out the part more endearingly than boisterously. Guilhoto portrays the father as a tragically hopeful man who cherishes reading and writing as his only lifeline to his memories, but ultimately realizes the profound pain of nostalgia. In a particularly moving scene, he begins to slowly and mournfully disassemble the room of string he had built for his daughter; winding the thread around his forearm, he watches as his gentle tugs erase the feeble structure, leaving an emptiness both onstage and in his eyes.

Opening with a scene on the beach, water dominates the play in many respects, flowing through metaphors. Under third-year scenic designer Sydney Purdue and fourth-year props master Charlotte Rieder, Ruhl’s raining elevator, dripping sounds, water pump, and River of Forgetfulness are augmented with ripples painted on the floor, bubbles that rain upon the actors, and a real-life pool acting as the river. First-year costume designer Ashby deButts reincarnated the chorus of Stones as algae-adorned formations with crowns of coral woken from their slumber on the seabed; they are a cranky, blue-faced lot that serve as a modernized Greek chorus. Transitions between water and land, between life and death, are completed by lighting designer Eric Karsten. The set is plunged underwater by a melancholy blue light and resurfaces with much warmer yellow lighting. These changes underscore the vast distance between the underworld and the world above—between Eurydice and Orpheus.

Ruhl’s original script allows adaptors of the play a considerable amount of creative leeway. UT’s production handles that freedom effectively: Their stylistic choices and additions are emphatic and significant rather than cosmetic. Whether it is the costume designers or the actors, the whole production’s efforts show through in conveying the tearful tale of Eurydice and her husband Orpheus.