“The University has used the Kalven Report as a kind of shield and hasn’t really engaged as much as it might in these things. To invoke it as this absolute principle is not, I think, what they had in mind. It’s important that these be real conversations, and that the University not just reflexively hold up the Kalven Report as the Holy Grail.”

That’s Jamie Kalven, the son of 1967 Kalven Report Committee Chairman Harry Kalven. He believes that the University is using the Kalven Report in a less flexible way than its writers had intended, and that this application is to its detriment as an institution.

As protests against the Vietnam War reached their peak, Harry Kalven, the Harry A. Bigelow Professor of Law at the time, and several colleagues sat down to articulate what they believed the University of Chicago’s role should be in conversations about moral and political controversies.

In the half-century since 1967, the resulting statement—known as the Kalven Report—has guided the University’s response to a host of societal issues. Kalven and his colleagues determined that while the University is the home and sponsor of critics from every side of a debate, the institution itself should not take a position on any controversy not of “paramount value” to the University as an institution.

Jamie Kalven pointed out how situations at the edges of acceptable free speech tend to bring the Kalven Report into the discussion, necessitating an ongoing conversation about its scope.

After his father’s death, Jamie Kalven spent 10 years finishing the book about the First Amendment his father was working on when he died. As such, he has a unique insight into Harry Kalven’s views on the limits of free speech and how these could factor into a document like the Kalven Report.

“My father’s position was that the First Amendment is almost an absolute, but everything hinges on that ‘almost.’ We have to be prepared to have that argument again and again in those types of situations, and that’s a good thing,” Jamie Kalven said. “If it’s an absolute, people just sort of apply it reflexively, thoughtlessly, and don’t really grapple generation to generation with the nature of the principle.”

The question, then, is what constitutes an issue “of paramount value” for the University.

“What falls within that exception of paramount values? Does the Vietnam War, does South Africa, does climate change? Didn’t the University express formally and publicly as the University against the Muslim ban? The way the University handled the Muslim ban was an example, and an honorable one, of how the University might respond in such circumstances,” Kalven said.

Is it of paramount value to the University if a far-right organization uses posters to name students and faculty members as anti-Israeli terrorists? Dean of the College John Boyer referenced his own children and grandchildren, one of whom is about to start college, in response to the question.

“If I were a parent, I would want the University to help, and to not have it be seen as a geopolitical thing,” he said. “Universities need to do what they think is the right thing.”

The University has taken a position on some of the current presidential administration’s decisions, including the rollback of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and the travel ban that limited entry to the U.S. for citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries. However, the University addresses these issues on an as-needed basis in determining what is of “paramount value,” which Kalven believes appropriate.

A good university, according to the Kalven Report, is a controversial one.

The mission of any institution of higher education, the report says, is to discover and disseminate new knowledge. The report stipulates that the University must remain open to the whole of society, not closing itself off to any one viewpoint or criticizing one cultural norm while praising another.

If the University took a position on the prominent social conversations of the day—be it Vietnam, the South African Apartheid system, or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—the conditions for maximum academic freedom might be jeopardized.

The report writers also concluded that students and faculty members’ right to protest complemented this principle, and that limiting the speech of the University as an institution would safeguard the speech of every member of its community.

Some people on UChicago’s campus feel that some community members’ speech is more accepted than others’, however.

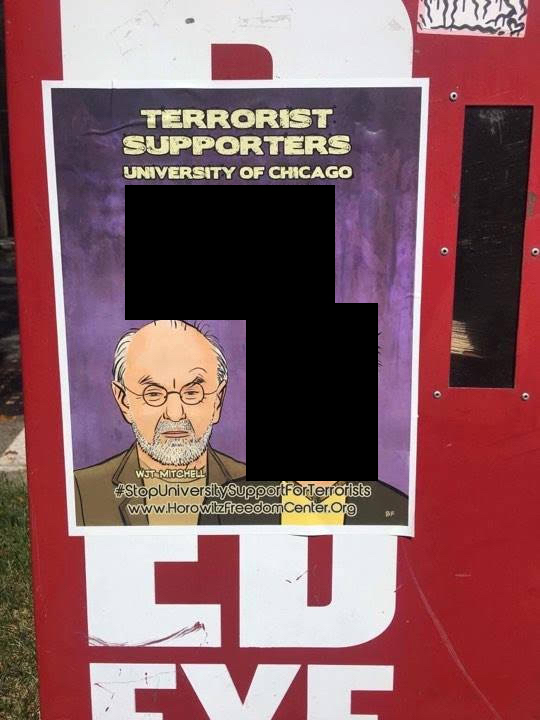

Shortly after the start of this past fall quarter, unauthorized posters accusing students and faculty of terrorism appeared around UChicago’s campus. Facilities Services immediately removed the posters, which listed 25 student names and the images of two faculty members. The people listed on the posters were associated with Registered Student Organizations supporting Palestinian rights, such as Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), Jewish Voice for Peace, or other student campaigns surrounding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The posters, Dean of Students Michelle Rasmussen wrote in an e-mail to students, violated University guidelines on appropriate posting.

“The university’s policies and public statements have made it clear that unauthorized postings are not permitted on campus. We have not contacted outside groups,” Rasmussen said.

The University reached out to targeted students afterwards to offer them emotional support, though it has not taken any further action. The University had condemned a similar set of Horowitz postings from last academic year, and sent out an e-mail discussing the most recent set, though some activists and targeted students did not feel it was specific enough, as the note did not name Horowitz or the action.

Horowitz took responsibility for the posters on one of his websites, which is part of his far-right network of organizations, the David Horowitz Freedom Center (DHFC), which has been classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Horowitz frequently targets the University, which has seen a wave of pro-Palestinian activism in recent years.

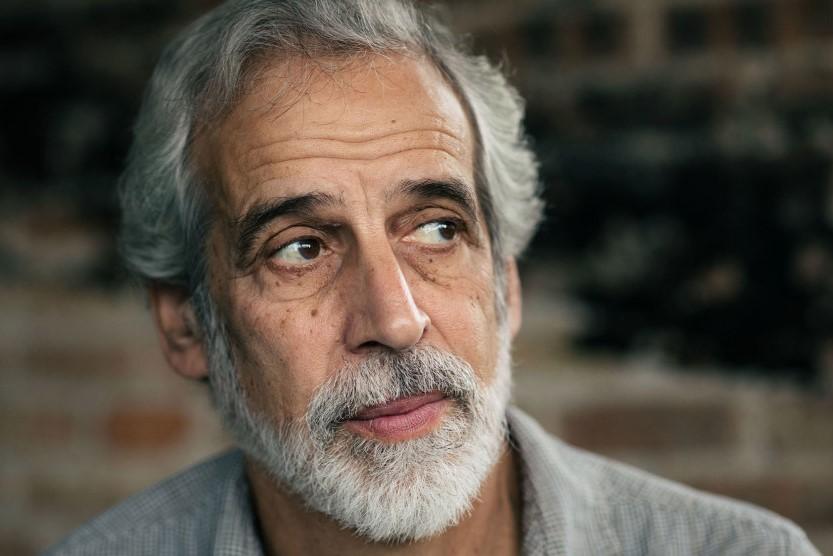

W. J. T. Mitchell, a professor of art history and English, was one of two faculty members targeted on the posters, which called Mitchell and the other targets “supporters of terrorism.”

Mitchell did not take this lightly.

“To claim…that I am a supporter of terrorism is more than just hyperbole. It’s really defamatory. If someone said that in 1975, terrorism didn’t mean then what it does now,” Mitchell said. “To be called a terrorist is very much equal to being called a Nazi, an anti-Semite…. It’s a very serious accusation.”

Mitchell noted that the DHFC likely collaborated with another far-right, pro-Israeli organization called Canary Mission. Canary profiles students and faculty nationwide whom it believes to be threatening to campus attitudes toward Jews, the United States, Israel, or Jewish presence in higher education.

However, Mitchell also noted that he is a tenured professor and therefore much safer than those most adversely affected by Canary Mission postings, which have targeted University students as well.

“I have a long public record. If someone wants to attack me, bring it on,” he said. “But for students to be labeled this way can be a killer to [their] career prospects, and this is more true today than it was then, because of social media.”

Mitchell and other targets have demanded that the University release a “cease and desist” letter telling Horowitz to stop coming to campus, that the University assist students in their reputation management, and that it collaborate with the other universities on the “Top Ten Worst Schools that Support Terrorists” list to coordinate a response to the DHFC as a group.

Law professor and former provost of the University Geoffrey Stone said that the content of the posters—which Mitchell had classified as defamation—gave no grounds for legal action.

“[Defamation] entails a factually false statement about an individual that defames their reputation, but it has to be factually false. The use of the word ‘terrorist,’ which I gather is part of the problematic issue, is hyperbole. It is not a factual statement, and it is understood obviously in that context,” he said. “You could not sue someone for libel in this situation, the same way you couldn’t sue someone for libel if you had an abortion and they called you a baby-killer.”

Stone, a First Amendment scholar, clarified that Horowitz’s actions cannot qualify as hate speech, because the concept of “hate speech” does not exist in United States’s legal terminology.

“The very concept of hate speech is so vague and ill-defined that nobody knows what it is. Neither the First Amendment nor University policy recognizes a category of hate speech that is not protected by the First Amendment or by the University’s principles on free speech,” Stone said.

Stone also chaired a committee to investigate the current state of free speech and students and faculty member’s right to it in July 2014, which culminated in the release of the “Stone Report.”

The Stone Report is the most recent in a series of University-commissioned reports which reaffirm the core principle of the Kalven Report, which has dictated the University’s response to the Horowitz issue, as well as many other political controversies on this campus—namely, an unerring commitment to maximum freedom of speech.

Today’s Stone Report raises a 1932 incident in which communist presidential candidate William Foster spoke to students at the request of a campus communist group. This invitation elicited alarm from onlookers and locals who viewed the University as a hotbed of left-wing radicalism. However, University President Robert Hutchins reaffirmed that the University’s students had the right to discuss any controversy they pleased, which included their right to hear from Foster.

Third-year anthropology Ph.D. candidate Alex Shams, a target of the Horowitz posters, found the University’s response to the posters confusing in the context of its free speech policy. Instead of prioritizing the free speech of all community members, he sees the University as prioritizing the rights of outside speakers over those of students.

He thinks that the University fears that condemning Horowitz by name would be construed as a pro-Palestinian political statement in favor of one side of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“I don’t think anyone has asked them to take a position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I’m afraid that…a big reason for the inaction around the targeting of SJP is that people consider our political views to be controversial,” Shams said.

To Shams, the free speech principles of the Kalven Report do not factor into the University’s possible response to Horowitz.

“I think the Kalven Report is [not] relevant to this situation unless we believe that anti-Muslim hate speech is normal politics. The only way the Kalven Report is related to the situation is if the University thinks an outside hate group is a normal political opinion to have,” he said.

Dean Boyer said that the Kalven and Stone Reports only derive their power from a community that holds them up and stands by them.

“The reports are only as good as the community behind them—they’re pieces of paper! What do your students believe in? What are your principles?” Boyer said.