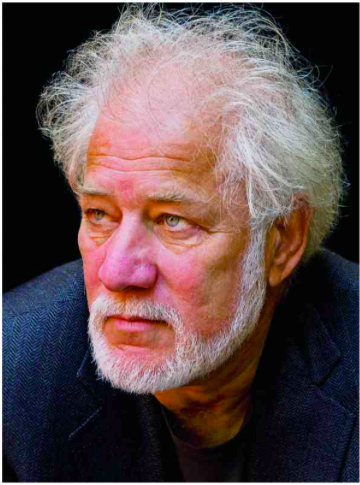

“‘In 1945, our parents went away and left us in the care of two men who may have been criminals.’ I had no idea where I was going after I wrote that first sentence,” admitted Michael Ondaatje as the audience burst into laughter. Ondaatje, the Sri Lanka-born author of seven novels and 13 poetry collections, visited the Seminary Co-Op this past Thursday to discuss his latest novel Warlight. He was joined in conversation by Sonali Thakkar, Assistant Professor of English at the University of Chicago. Included on Barack Obama’s 2018 summer reading list, the book delves into the nature of war, memory, and family.

Warlight follows 14-year-old Nathaniel and his older sister Rachel after they are abandoned by their parents and left in the care of the Moth, named after his quiet and secretive demeanor, and the Darter, a smuggler of racing dogs. After months of silence, their mother returns without their father, explaining nothing. The children’s story of parental separation and eventual reunion is a trope associated with fairy tales. Ondaatje plays with this idea, speaking through Nathaniel: “Whenever my sister and I recalled this story, it felt like part of a fairy tale we did not quite understand. Our mother told us about it without drama…the way things happen in twice-told tales.” The novel itself is such a twice-told tale, delivered in two parts, spanning over a decade. In the second part, an adult Nathaniel embarks on a painful journey of retelling and reconstructing his mother’s story, and by extension, his own. “It is like clarifying a fable, about our parents, about Rachel and myself…there are traditions and tropes in stories like this.” But as old secrets unravel and the family breaks apart once again, the prospects for a happy ending are grim. For survivors of war, it seems, the past never stays in the past.

The novel challenges the notion that the destruction that came about because of World War II ended in 1945. The word “warlight” refers to the dim ambient light that people and ships in London had to rely on to navigate the city at night, since blackouts were mandated to prevent enemy aircraft from using the city lights to identify targets. Ondaatje recounts, “When I was finding a title for the book, ‘warlight’ was apt because it was a reflection of war, a reflection that continued on like light on a cloud.” Thakkar added to his point, “It seems in a way like we’re still living in warlight. The emergency lights are still on and the bright illumination never quite returned.”

“It’s not romantic,” said Ondaatje about his experience in post-war London, which informed his writing of Warlight. “The version of England that I have [is] a place where whatever you were born into, you became that, simply. When I was in school there was no sense that you were going to suddenly become something unusual like a rock star or a writer. If you were from a family of laundromats you became a laundromat.”

Despite this, Ondaatje has managed to become one of Canada’s most renowned authors, where he relocated in 1962 to attend university. Over the course of the talk, he offered insight into his writing process, which could best be described as spontaneous.

“When some people write novels, they have all the research done, and then they can write the book,” he said. “But for me I have a tendency to do the research simultaneously.” He emphasized that he does not force his characters into molds, but rather lets them emerge organically.

“I never base characters on people I know because then I would be limited to what I know about them, and I know that person is much more interesting than [that],” said Ondaatje. His characters largely write themselves, and none of them turn out quite the way he planned. Still, others were not planned at all— “I wasn’t expecting the Darter to be in the book until he was there in the living room when [Nathaniel and Rachel] came back from school. Often some of the most interesting characters are the ones who turn up uninvited.”

Michael Ondaatje’s foray into a deeply scarred England is incredibly powerful. Although the novel’s ambiguous characters and melancholy progression land far from its fairy tale roots, Ondaatje hints that “there is more hope than you might think.”