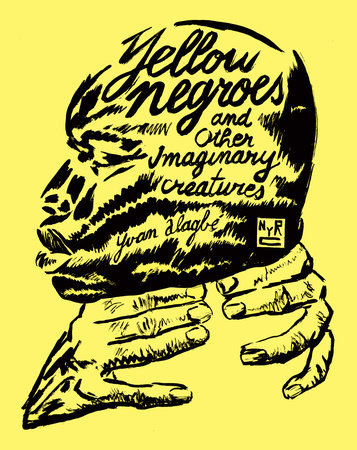

On November 18, French author Yvan Alagbé appeared at the Seminary Co-Op for a book reading and discussion of his acclaimed comic, Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures. Recently translated into English, Alagbé’s story explores the intersections of race, love, immigration, and politics in France.

Alagbé was born in Paris but spent his early years in West Africa and is well-versed in the struggles of the immigrant experience in France. The selection he read, in French and English, was about an immigrant cab driver. As he put it, he wanted to “bring you in the head of an African cab driver who works at night, who’s just driving and driving and driving.” His comic puts a unique twist on the stream of consciousness style; the panels focus on the thoughts that pass by the cab driver’s mind instead of the scenes that pass by his window. Alagbé stressed the importance of honesty in portraying the cab driver’s thoughts.

Moreover, Alagbé spoke of the social reality of many immigrants of color in France, citing the often-false perception people tend to have of them. Not many people, he noted, are fully aware of the hardships of being an illegal immigrant. For example, he talked about how many Black immigrants spend decades in France, and even have the appropriate documentation, but still might not be considered citizens. By contrast, Polish immigrants are often accepted by French society after living there for only a year or two.

According to Alagbé, Yellow Negroes is a blend of fiction and reality, and as he blatantly proclaimed, “he is all the characters.” A deeply personal account of his experiences, the comic serves as a way to enrich the immigrant’s narrative as it currently stands formed by mainstream news outlets. Even the title itself is supposed to be disconcerting; Alagbé discussed how he considered calling it by another, more derogatory name to reflect the shock he felt at the historical context of such slurs. Alagbé’s goal with the book, it seems, is to challenge the widely accepted portrayal of immigrant France.

The comic, which is an anthology of short stories, was written between 1994 and 2017. Many other comics at the time of Yellow Negroes’s inception were rooted in the superhero paradigm. Alagbé challenged the genre by grounding his story in a deeply political plot and setting.

Working as his own publisher, Alagbé was able to have total control over his book. Through veiled criticism, he discussed the role money plays in large publishing companies. The integrity of a story can be compromised by what publishers think will make the most money. Alagbé wanted to “serve” his book, not just exploit it for economic purposes.

Alagbé also emphasized that he considers himself a writer rather than a painter; for the innovative author, images can be used to enrich the story he is telling. On his aesthetic choice, Alagbé recalled that while the pictures are captured in black and white, he did not want that to entirely reflect the race of his characters. In other words, characters drawn with black ink are not necessarily Black.

In reference to contemporary French politics, Alagbé explained how “even the good guy is kind of mean, actually,” referring to French politicians. The rise of far-right political ideologies targets immigrants not only in the U.S., but in France as well. Alagbé expressed his concern for the strength of the far-right’s influence in conversations about immigration, and the shallow perception of immigrants by those in the political world. Citizens and politicians alike fail to take into consideration the hardships that lead people to leave their home country in the first place.

Although Alagbé spoke grimly on the political state of affairs, he had bright eyes when he described the new wave of politically and socially inspired comics and graphic novels. This new wave of storytelling can be used to give voice to experiences which have been hidden away by oppressive and overpowering structures. Now, Alagbé believes, those stories can be heard.