Last Monday night in the Doc lobby: Dozens had lined up for the A24-sponsored advance screening of Gaspar Noé’s latest release, Climax. Some people were grooving along to the soundtrack being played at the table outside of the screening room, others were theorizing about what the movie would be like, and others still were debating how good the movie would actually be. When the doors opened, I followed as an excited crowd hurried into the theater. After 98 minutes of dancing, disco music, and drug-induced delirium, the lights came back on. Whatever was left of the audience let out a collective “What the ACTUAL fuck?” and offered no applause. This was a very fair response to *Climax*; given Noé’s canon, perhaps it was even expected. All films have their ups and downs, but none that I have ever seen have as drastic extremes as this one. Gaspar Noé—what?

The first third of the movie was perfect. From the very first shot, Noé reminds us that he is a master of the free-moving, omniscient camera that so defines his cinematic style. He subverts traditional cinematic rules by diving into a full credits scene, which elicited audible “huh”s of confusion from those around me. Midway through the credits sequence, he notes that *Climax* is based on the true story of a French dance troupe in the ’90s. Noé’s opener, front-loaded credits, and subsequent character introductions are ingenious. On a retro-looking TV, the film’s dancers are interviewed one by one about their lives, their relationship to dance, and their dreams of success and an American tour. The TV is flanked by the movies and books from which Noé draws inspiration, such as Suspiria and a work by Fritz Lang. Though somewhat heavy-handed, these nods to classics of the genre actually came off as wholesome and lovingly nostalgic. The film then launches into one of the best dance sequences in cinematic history: a blend of hip-hop, vogueing, and the classic French tecktonik set to a remix of Cerrone’s powerhouse of a song, “Supernature.” Shooting all of this in one long take—which then continues for minutes after the performance ends—demonstrates restraint and maturity in Noé’s often-flashy form of almost free-floating cinematography. Then comes the sangria, and with it the film’s rapid decline in quality. An unknown character slips large amounts of LSD into the dancers’ drinks, resulting in an uncomfortable and upsetting hallucinogenic trip that comprises the second half of the film. If Noé had tinged this with black humor, it could have worked in the film’s favor. Instead, however, the film is inundated with extended talk and graphic depictions of sexual assault, incest, forced miscarriages, murder, suicide, and group hysteria. Everyone who didn’t walk out of the screening seemed to constantly alternate between hiding in their chair, leaning forward with mouth agape, or just shaking their head.

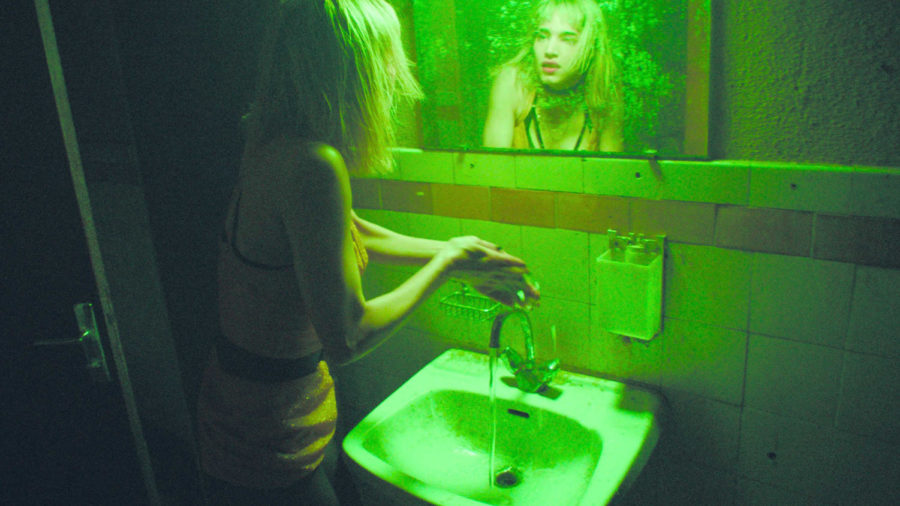

After an hour of evil and depravity, Noé’s filmic talents became tiresome and lost all redemptive qualities. The Dutch angles he would often use became off-putting, and the saturated red lights went beyond the giallo-inspired camp and just came off as tacky. The only thing I could stomach by the end was the energetic soundtrack, curated in part by Thomas Bangalter, one-half of electro-pop duo Daft Punk. Even this I could only manage to appreciate if I closed my eyes and consciously blocked out the dialogue and cries on screen. Gaspar Noé loves to shock and disgust with his art, but this was too far, and it rendered his film devoid of any artistic qualities.

Rife with intertitles, Climax oozed pretentiousness. Noé opened the dance sequence with the statement that his is a French film and that he is proud of that (“presentent un film français et fier de l’être”). Arrogant, especially when shown to an American audience? Sure. But not only is this statement a lie, it also exposes Noé’s deep hypocrisy. Firstly, the subtitles censor and make a lot of the dialogue more palatable, especially around conversations about assaulting men and women. If he were proud of his French identity, why alter the basic language itself? Secondly, there’s nothing in the movie itself that is quintessentially French, except perhaps for the cigarettes and tecktonik dance. Even the music heavily featured American musicians.

One could say that Climax is to ABBA on LSD as Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless is to jazz—there is a clear reference to the father of the French New Wave’s use of fast music to pace the cuts, plot, and overall aesthetic quality of the film. Yet, that in no way makes up for all the terrible, pretentious, and incredibly problematic features of Noé’s movie. In the end, it seems more that Noé and his team presentent un film terrible et fier de l’être. That was the most people I had ever seen walk out of a movie, let alone a free advance screening. I will admit, however, that I cannot stop listening to the soundtrack (please blast Cerrone’s “Supernature” on repeat at your next party).

To borrow a final quote from a fellow audience member: “Jesus Christ, I never want to do drugs after seeing this.” So, thanks for that, I guess, Mr. Noé.