I recently visited the Special Collections Research Center at the Regenstein Library to see the exhibition Discovery, Collection, Memory, in celebration of the Oriental Institute’s centennial. Students on their way to and from long midday study sessions bustled around me as I stood in front of 100-year-old archival photographs of an archeological excavation. Beyond the clear glass doors, the campus seemed to be focused on the future, teeming with new ideas and developments. Inside the Special Collections Research Center, however, I took a step into the past—though not quite as far into the past as one might think.

Among 3,000-year-old ancient Egyptian coffins and Persian monuments lies a collection of objects from a more recent past, one that tells the story of the Oriental Institute as a museum and institution. The research archives give another dimension to the museum collection, showcasing the discovery of ancient history. With over 40,000 square feet of photographs, excavation materials, and documents, the research archives are not usually open to the public, but according to Anne Flannery, the director of the Oriental Institute archives and the curator of the Special Collections exhibit, “the institutional history of the museum is important to understanding what it took to get us to this point—it lays the groundwork for the collection and enhances visitors’ understanding of the objects.”

Upon arrival, visitors are greeted by a carefully laid out arrangement of glass display cases that trace a path through the room, starting with the founding of the Institute and meandering its way through the expeditions and acquisitions of the early 20th century. The exhibit finishes with a pair of archival films that include footage from the groundbreaking of the museum in 1938, allowing visitors a glimpse not only into the history of the Oriental Institute, but also into the formation of the University’s campus as it appears today. Although both the archival exhibit and the main collection can certainly be viewed separately, the former is certainly worth a visit.

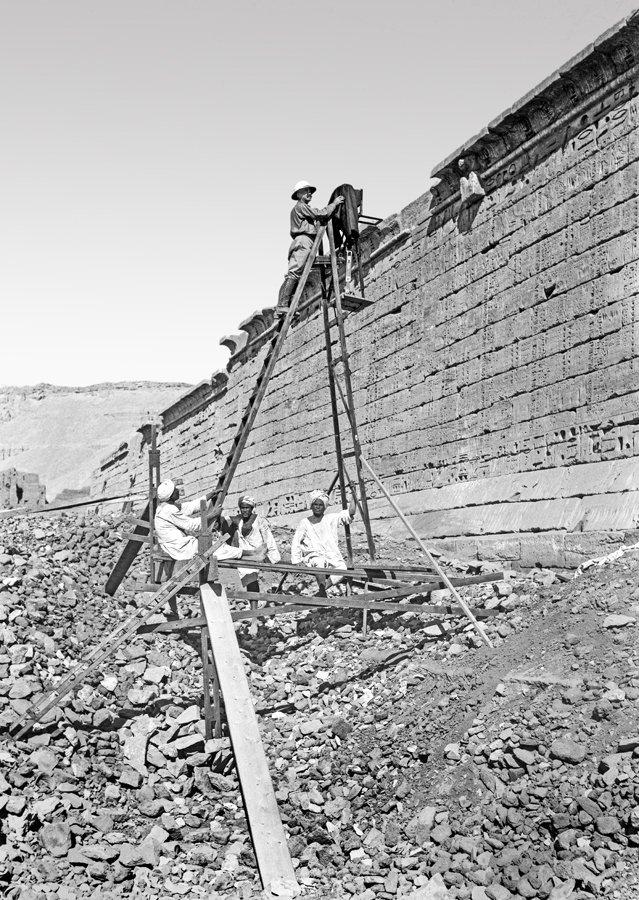

The highlight of the exhibit uncovers the story of the museum’s two largest artifacts: a massive human-headed winged bull statue in the Assyrian gallery, and the monumental depiction of King Tutankhamun that greets visitors entering the Egyptian gallery. Seeing these sculptures at the museum, their permanency is striking—it’s almost impossible to imagine that either of them have ever been moved from their pedestals, much less halfway around the world. This perception is challenged, however, upon seeing the archival footage of lifts and destroyed walls; the statues devolve into fragments in the photographs, forcing a new perspective on their life. For objects originally designed with the intent of permanency, they have been changed, moved, disassembled, assembled again, giving them a history beyond ancient history and a new meaning in the present.

Taken from their original location, the objects in the Oriental Institute travelled thousands of miles to find a spot in a museum in Chicago; confronted with this fact through archival photographs, the complicated colonialist history of the Institute comes to a head. There is no mention of this history in this Special Collections exhibit, as the curator wished to provide these complicated topics with “exhibits in their own right,” rather than devote only one small display case to such a complicated history. And while there may not be room to showcase this topic in a small exhibit, the Institute may wish to reflect on its past while looking to its future during its 100th anniversary.