This Saturday, social workers and activists discussed interpersonal violence at the Phoenix Survivors Alliance’s (PSA) second symposium of the year. The symposium, held in the Reynolds Club, aimed to spread awareness of activism around sexual assault happening in Chicago universities.

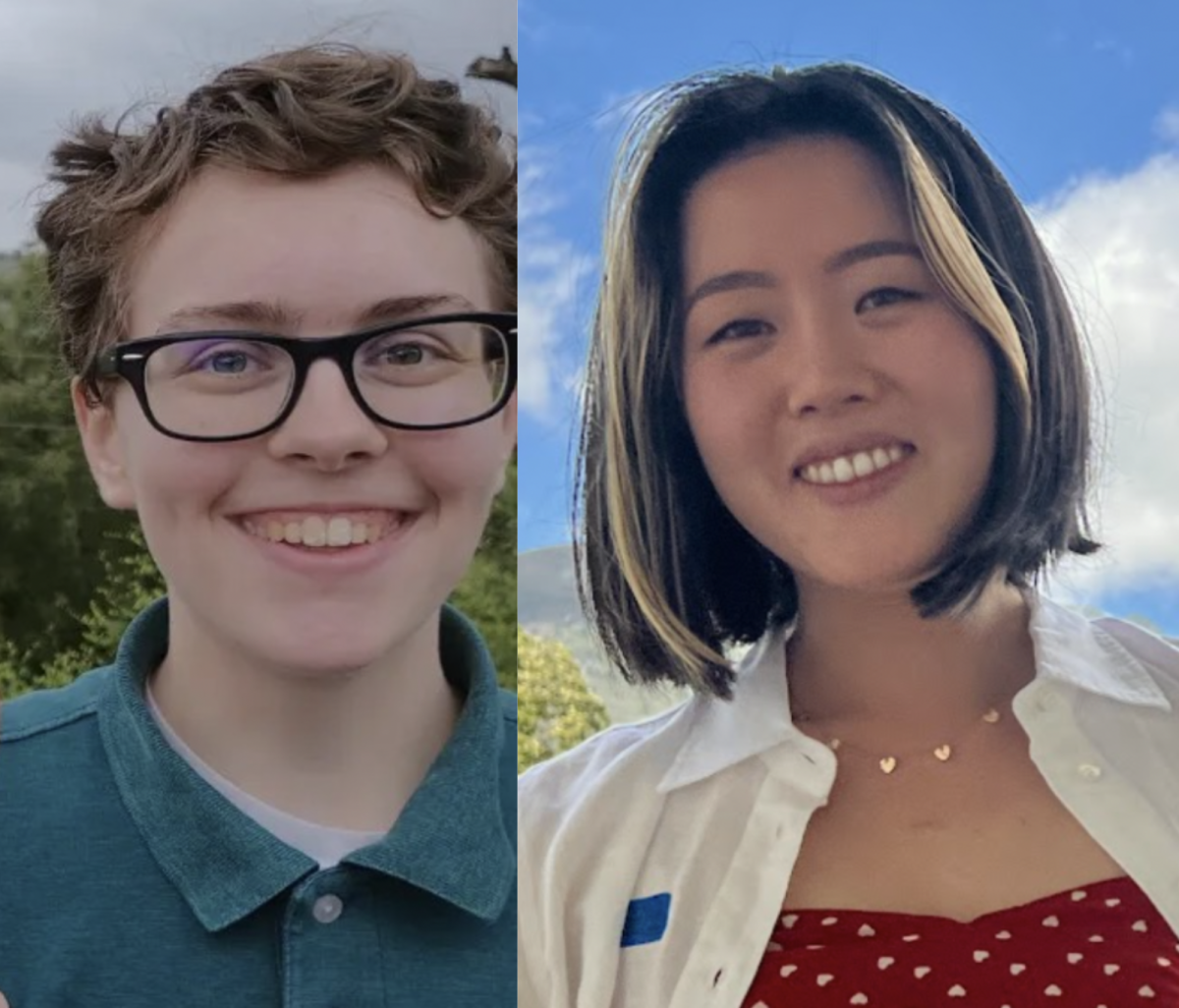

Saturday’s theme was interpersonal violence, which speakers defined as sexual, physical, and emotional violence enacted by a romantic partner, family member, or other intimate relation. PSA invited Danielle Boachie and Emma Gonzalez, both Chicago social workers, and Fabiana Diaz, an activist.

Boachie argued that patriarchy and capitalist profit have led to the development of a relationship between government, capitalism, and social organizations that control and derail anti-establishment, grassroots activist movements which she called the “nonprofit industrial complex.”

As a social worker themself, Boachie has experienced the disconnect between services provided by industrial nonprofits and the needs of marginalized victims of interpersonal violence.

“I think most importantly for me is [the nonprofit industrial complex’s] redirect of activist energies into career-based modes of organizing, instead of mass-based modes of organizing capable of actually transforming society. So, how does this look in practice? In Chicago, we have agencies that appropriate activist sentiments while relying on carceral practices to address gender-based violence,” Boachie said.

Since interpersonal violence is often waged through manipulation and coercion, it is uniquely perpetuated by these systems which uphold harmful power dynamics, Boachie said. They outlined the ways in which the police and district attorney institutionalize interpersonal violence by criminalizing victims who acted in their own self-defense. Furthermore, they identified a pipeline for marginalized groups between surviving violence and being incarcerated.

Patrick Johnson and Tewkunzi Green are two examples of this pipeline. Johnson was convicted under the state’s accountability theory law because he was present when his abusive boyfriend committed murder. Green is a mother who killed her partner in an act of self-defense, when he threatened her life while she was holding their child. Activists from grassroots organization Love & Protect are raising awareness of these cases at the state level.

Boachie used Love & Protect as an example of productive, anti-institutional activism. “Approaches taken on the social justice level, as opposed to through the institutions, are collective, action-oriented, coordinated, holistic, transformative, restorative, and centers [on] those most impacted by social violence,” Boachie said.

Emma Gonzalez, whose work focuses on prison abolition and decriminalization of victims, echoed Boachie’s message. “Obstruction can be as little as not laughing at a joke that is at the expense of survivors, or as grand as bystander intervention and protests on your local college campus,” Gonzalez said.

She stressed the importance of education and storytelling to work against the marginalizing forces that silence victims’ stories and fostering understanding and solidarity within and outside the movement. Amplifying survivor stories, like those of Johnson and Green, can also prevent further criminalization of victims, she said. “A survivor does not fit the image of a perfect victim, but instead of a woman or girl that shatters this nonexistent reality by surviving their abuse and interpersonal violence,” Gonzalez said.

Speaker Fabiana Diaz became an activist in college after being raped. She extended her activism to politics, sharing her story as a survivor since then and using it to empower herself and other survivors.

Because she was raped on her second day of college, Diaz never got to experience college without the backdrop of her assault. She recalled herself in the hospital afterwards. “I could see my poor immigrant parents’ hearts breaking. My mom just kept saying, ‘How could this happen?’ But what she meant was, How could this happen here, in the U.S., in a country that was supposed to provide her daughters opportunities?” Diaz said.

Diaz remembers feeling like she was constantly losing—institutional forces made it so that she had to alter her life to avoid her rapist: She was the one who had to rearrange her class schedule and move dorms when placed in environments with her rapist.

In protest, Diaz completed her first act of activism. Inspired by a student who carried her mattress with her through campus until her rapist was held accountable by their university, Diaz did the same.

“That was the first time I fully embraced the identity of a survivor, something that took me many years to unpack and fully understand: how does it fit with all my other identities; how at times it felt like my only identity,” Diaz said. “I became a survivor publicly. I didn’t realize it then, but my activism started to save me. The more I shared my story, the more survivors I met, the more power I reclaimed, the more agency I felt.”

Through her activism, Diaz found camaraderie and connection with other survivors. “Sharing your story is a privilege,” Diaz said. Many survivors struggle to speak of their trauma as stigma around sexual assault persists. Diaz experienced this with her own family in Venezuela, whom she had not told her story to until appearing at the Oscars. Both Boachie and Gonzalez agreed that storytelling is an important healing mechanism for victims and is also a necessary tool to raise awareness for interpersonal violence and combat survivor stigma.