Following the University’s announcement on March 12 that spring quarter would be conducted remotely, students were given 10 days to vacate campus. For most, the closing of campus meant vacating campus and returning to their family homes. For low-income students, there were barriers at every step of the transition. Some say these barriers will continue through remote learning.

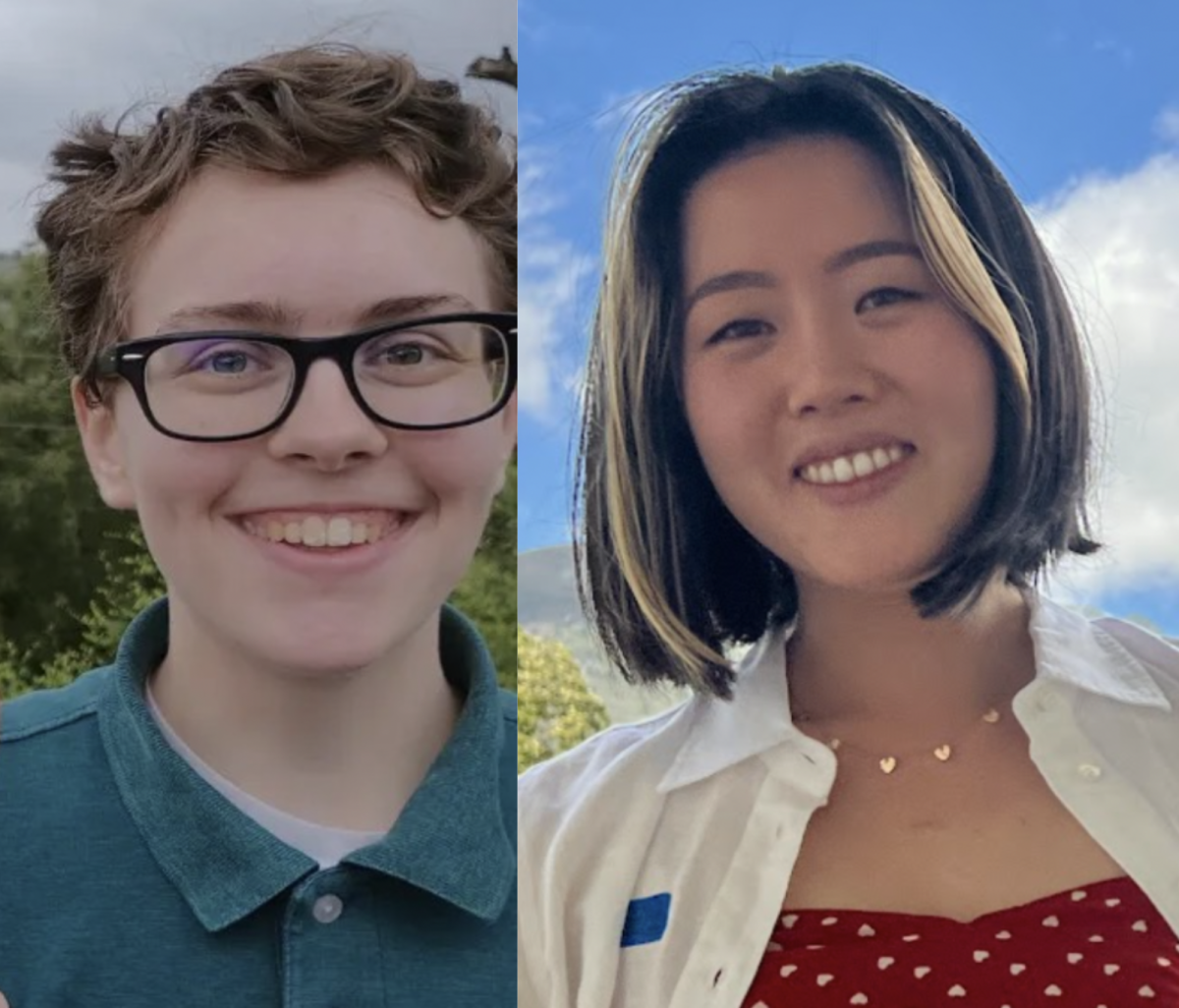

Second-year Yuri Sugano, an organizer for UChicago Mutual Aid, said that the transition to the stay-at-home order was complicated by economic factors. “When the news came out it was unexpected. And, of course, I considered going back home but then it’s a matter of, ‘How am I going to afford plane tickets? How am I going to afford storage?’ It’s just problems added to problems,” Sugano said.

*The Maroon* also spoke with third-years Naa Asheley Ashitey and Kiana Hobbs, the president and vice president of UChicago’s QuestBridge Scholars, who provided commentary, independent of the QuestBridge organization, on their experience as low-income students.

Hobbs said that the decision to transition to remote learning left low-income students “scattered.” According to Hobbs, most low-income students don’t travel home for spring break because of the high costs, so last-minute flights home were expensive. Furthermore, many low-income students are financially independent, relying on financial aid and campus jobs to support themselves, so the unforeseen economic burdens of the transition left many students’ financial stability threatened.

“Disposable income is not a term known to many low-income students. It’s not a thing that happens. If some students are lucky, they can have an emergency savings but many students are supporting their families with that or they have to pay for food and all of these other costs. So, there’s not much leeway for lost income or surprising unexpected circumstances, such as this,” Hobbs said.

With the closing of campus, students are losing on-campus resources such as food security, reliable technology and internet access, fitness centers, and libraries. Ashitey used the importance of Hutchinson Commons’ Saturday night meal program as an example of low-income students’ dependence on these resources. According to Ashitey, before the meal program was created, students who could not afford to dine out would starve when the dining halls closed on Saturday nights.

Unique challenges faced by low-income students range from obtaining reliable internet and devices to attending classes and keeping up with schoolwork when fielding additional responsibilities. Ashitey was fortunate enough to have an emergency fund she could put toward supporting her father in Ghana, but has lost the savings which she planned to use toward graduate school. She shared that finals week was particularly difficult for her as she balanced all these challenges, resulting in her turning in an assignment past the due date for the first time in her college career.

Ashitey and Hobbs explained that the low-income experience is characterized by responsibility and uncertainty, which complicate their already tenuous economic situation. Many low-income students are returning home to domestic responsibility and economic instability. One student came to Sugano through Mutual Aid seeking advice on how to support his family, which he typically sends half his quarterly stipend to, now that he had lost his on-campus job.

According to Sugano, in the worst cases, first-generation low-income students must return to domestic violence. “It’s sad that no one is thinking about these problems, but they do exist,” Sugano said.

Under these conditions, the University has been taking steps to accommodate students and smooth the transition to remote learning. According to Sugano, although the University was delayed and disorganized providing relief, almost all missing campus resources have been accounted for. The University has committed to honoring financial aid this quarter and also agreed to increase financial aid for students who demonstrate need for greater support at this time. The Office of Career Advancement is offering Micro-Metcalf opportunities to alleviate the impact of lost campus jobs. Sugano said that Odyssey Scholars received advance quarterly stipends and that, personally, he has found the University’s technology grants helpful in securing reliable internet access for his spring quarter classes.

However, financial support does not fully compensate for the academic challenges faced by low-income students under the present circumstances. To address the issue, the University put in place an opt-in pass/fail grading system for the quarter. While Ashitey was pleased that this pass/fail option was more accessible than expected, she still believes that a universal A system would be more accommodating to low-income students because it would prevent academic failure altogether.

Ashitey said she is more concerned with the lack of commentary from graduate schools on whether they will accept alternative grades and if they will treat students impacted by these circumstances with academic leniency.

“It’s hard to comment on pass/fail because in a lot of instances it’s not just undergraduate dependent. It really is dependent on where students want to go in the future. And there needs to be a responsibility that law schools, grad schools, medical schools take in saying, ‘Hey, it’s okay if you do pass/fail this time. We’re gonna take it.’”

Despite the importance of higher education and the resources it offers low-income students, Ashitey disagreed with the way college has been portrayed as a “great equalizer” in recent discussions about the impact of coronavirus on first-generation low-income students. She believes the term ignores the remaining inequality on campuses. Hobbs explained that low-income students have been “playing catch up” in the classroom coming from public schools that lack funding and resources.

“You can eat at the same dining hall, you can live in the same dorm, but when you’re a low-income student, you’re a first-generation student. For example, if you’re a Black student, and you’re a part of all those, or you’re a queer-identifying student, the steps you take on the sidewalk going to class…will forever be different than someone else’s,” Ashitey said. “Classes are not taught in a way that is completely accessible to students like me.”

However, Hobbs and Ashitey agreed that the loss of on-campus resources through remote learning threatens to exacerbate the inequalities for low-income students that already exist in higher education.

“When you come back home, those differences are now even more escalated because you’re going back to a place where you’re trying to be that same university student in a place where you don’t have the same access to the resources you did have while you were on campus.”

That “doesn’t mean that it’s easier for low-income students on campus, because the fact of the matter is it isn’t. But at least [low-income students] could get to those resources on campus. Now they can’t. So, everything just gets added more and more,” Ashitey said.