“Decolonize your mind!” reads a lovely, lilac-colored infographic on the Instagram story of a fellow first-year. The ostensibly Canva-created post implores us to forget historical narratives that center whiteness, likening the act of unlearning or pursuing an anti-racist education to the act of decolonization. But decolonization is not simply a set of readings or documentaries for white folks and non–BIPOC to assuage their settler guilt. Decolonization is the radical, transformative repatriation (or rather, rematriation) of land for the Indigenous peoples from whom it was stolen.

The adoption of decolonization as a tool for learning, though noble, erases the radical origins and radical futures of the cause: dismantling settler colonialism and the institutions that perpetuate it. It’s not only inappropriate to appropriate decolonization in issues not related to the settler-colonial state—it’s also impossible. You cannot “decolonize” abstract spaces of whiteness. As follows, you cannot “decolonize” spaces built upon oppression without fully dismantling them. Anything less would be performative and reductive.

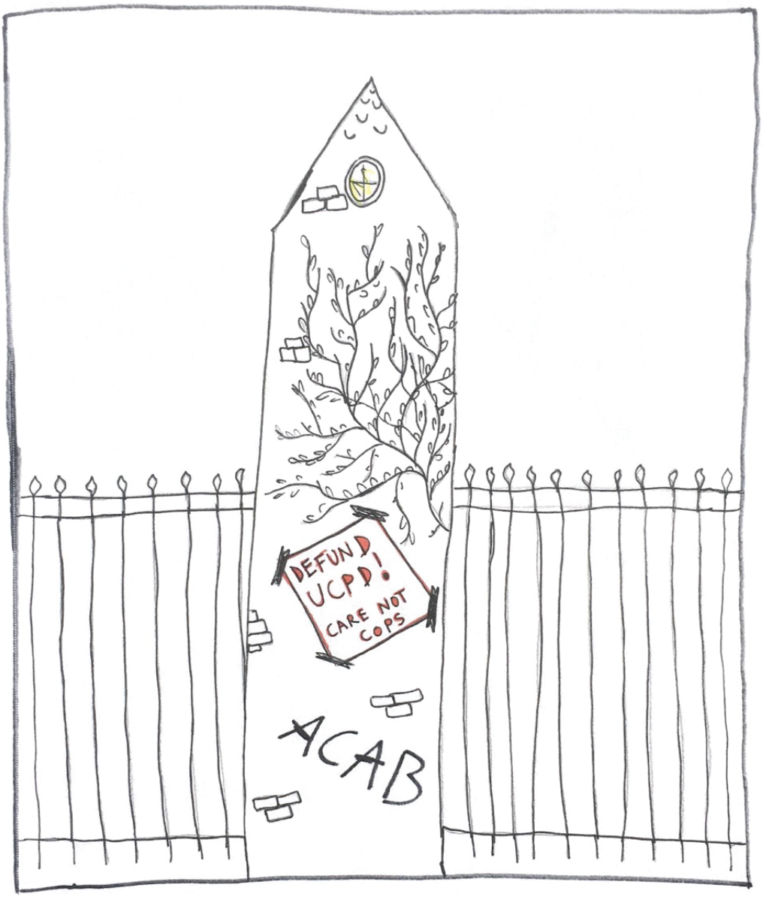

Our own school makes for a wonderful example. Nothing short of abolition of the University as we know it will suffice. You cannot “decolonize” a neoliberal university that will continue to prop itself up at the expense of its students. Accordingly, we must move past the university model rooted in capitalism and towards one focused on students and education for education’s sake. We must abolish the systems of harm that claim to protect us (namely, the UCPD) and learn to practice radical care in our communities.

UChicago has proven itself to be a business first and a place of education second. On the individual level, the University isolates students within its capitalist framework, which second-year Noah Tesfaye better articulates in a recent column. The stress and toxicity in the academic culture the University breeds is merely an expression of market competition. Our four years are marked by the idea of individualism to further our own careers. We pay for our education, we receive it, we enter the workforce (often with mountains of debt); we are products of the academic institution. Education is stripped of all possible intrinsic good or social good—it is a necessary expenditure insofar as it can benefit the individual. This culture is simply not sustainable: To prioritize joy and true fulfillment in education, we must adopt an anti-capitalist approach to our academics and call on the University to make systemic changes to that effect.

Another aspect where our current model of the University has failed us is in establishing safety. In the name of safety and security, the University has amassed one of the largest private police forces in the nation. But UCPD has failed to provide genuine safety—instead, its officers terrorize Black and Brown students and members of the Hyde Park community, and consistently fail to protect victims of sexual assault and misconduct. As Kelly Lo, a representative of Phoenix Survivors Alliance, stated this October at a Student Government town hall with the University administration, “safety exists in the spaces where investment is given into healing and community instead of policing.” To truly protect and serve our communities—the student body of UChicago, yes, but also the surrounding neighborhoods—we must invest in and prioritize community solutions, as well as do away with the oppressive institutions that claim to help us.

Despite the dangers of using decolonization as a framework for progress, a call for decolonizing UChicago is not as far off as we might expect; the University has propped up colonial systems globally, actively benefiting from American imperialism and racial capitalism. The administration has time and time again used its infamous Kalven Report as a shield, even justifying, in one instance, complicity in genocide. The two-page report was written in 1967 as a response to the student protests on campus against the Vietnam War and maintains the University’s neutrality on political and social issues. For the sake of “an extraordinary environment of freedom of inquiry,” the administration refused to divest stock from companies doing business in South Africa during apartheid in the 1980s. This happened again in 2006 with companies "identified as being complicit in the Darfur genocide," despite significant pressure and peer institutions choosing to divest their own endowments. Additionally, the University has ties to companies that enable Israel’s human rights abuses in Palestine, including Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Raytheon. To this day, as reported by The Maroon, the University has investments in fossil-fuel companies, companies involved in deforestation, and weapons manufacturers.

UChicago’s unsavory investments are consistently met with student backlash and protest. Nevertheless, the administration has historically been steadfast in their commitment to their monetary sources—and we should expect no different from such a quintessential neoliberal university. After all, the administration will protect what is most valuable to it: money, not students.

So how can we reconcile our reality with the fact that UChicago as we know it must be abolished, as we attend our classes and walk through the quad every day? We must fundamentally reimagine the University. We must shed the myth of individualism and learn to think in terms of the many. We must grow our relationships with our peers, prioritize collective safety over the safety of products, and strengthen our ties with the greater South Side. The work UChicago United is doing is critical for the cause: #CareNotCops, #EthnicStudiesNow, and #CulturalCentersNow are building power by creating coalitions and conducting impactful direct action that challenges the administration and grows the movement. They are daring to imagine a better University, one less beholden to capitalism and more focused on community. We must uplift and organize with these campaigns.

Abolition can sound like unmaking, like something destructive. But there is joy and creation in the community that comes during, and after. If every action we take is towards liberation—towards transformative, restorative justice—then we are not unmaking; we’re rebuilding. Abolition is a lofty goal—and true decolonization all the more—but a worthwhile one, especially when we can begin the work today.

Kelly Hui is a first-year in the College.