Patrick Jagoda, UChicago professor in English and cinema and media studies, Guggenheim fellow, and executive editor of Critical Inquiry, is a highly achieved academic. But his investigation as to what defines a game in a world in which the line between games and productivity is increasingly blurred is not so conventionally academic; it is awash with pop culture references, memorable quotes, and pithy commentary.

Jagoda’s discussion of his new book, Experimental Games: Critique, Play, and Design in the Age of Gamification, fittingly began with active engagement of the audience. Just as most games demand a certain level of constant attention, Jagoda and his cohosts Alenda Chang, author of Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games, and Ashlyn Sparrow, assistant director of UChicago’s Weston Game Lab, requested that the usually passive Zoom participants participate in the talk through a Kahoot quiz.

Jagoda joked, “You probably weren’t expecting this at a book event, but here we are.” The enthusiasm with which the audience responded to a glorified quiz poses a question: How does Kahoot manage to make quizzes feel like games, rather than the kind of imposition that one would normally associate with quizzes?

The process that Kahoot has mastered is that of gamification, and Kahoot isn’t alone. As Sparrow put it, “The process of using game mechanics in traditional non-game activities is all around us. We have Fitocracy, Fitbit, My Fitness Pal, and Nike Plus gamifying exercise, Khan Academy gamifying education and learning, and consumer rewards programs actually even gamifying loyalty…. The language of competition, leaderboards, and points have taken over mundane aspects of our lives.”

Sparrow and Chang explained how in Jagoda’s view, this “language” developed alongside neoliberalism. Chang said that Experimental Games reflected on how the “post-industrial growth of neoliberalism and informatics informed the development of games.” Sparrow was of a similar opinion. “These psychological and developmental design practices are not a recent development. In Experimental Games, Patrick Jagoda has definitely connected the rise of games and competition to neoliberalism,” she said.

But what exactly is so experimental about games when they’re integrated into our daily lives? Sparrow notes that Jagoda doesn’t believe that all games are necessarily experimental: The title merely indicates his wish that more games were. According to Sparrow, Experimental Games intends to answer a major question: “How might we push the simple idea of gamification and neoliberal thought and use games as a form of experimentation that allows its players to shift its relationship with the world?”

Although Sparrow touched on Jagoda’s motivation for writing this book through that key rhetorical question, Jagoda had the opportunity to share his direct inspiration: “Every book I’ve worked on or want to work on begins with a concept that causes me discomfort.” When it came to Experimental Games, the discomfort he experienced was the “tension between what games are and what games can be.”

However, the experience of writing the book was invaluable to Jagoda, helping him determine “what kind of game designer…to be over the next decade.” Jagoda is exceedingly aware that the world of gaming is riddled with inequities, showing concern about how to most effectively diversify games and eliminate the bigotry often seen in video game storylines. He asked himself, “If video games are complicit with militarism, sexism, racism, and so forth, what does it mean to make games that both acknowledge and exceed those kinds of coordinates?” Writing Experimental Games forced him to ponder “what a game does to you as a player in a medium-specific way: how it impacts your body, your thinking, your habits, your beliefs, your ways of moving through the world.”

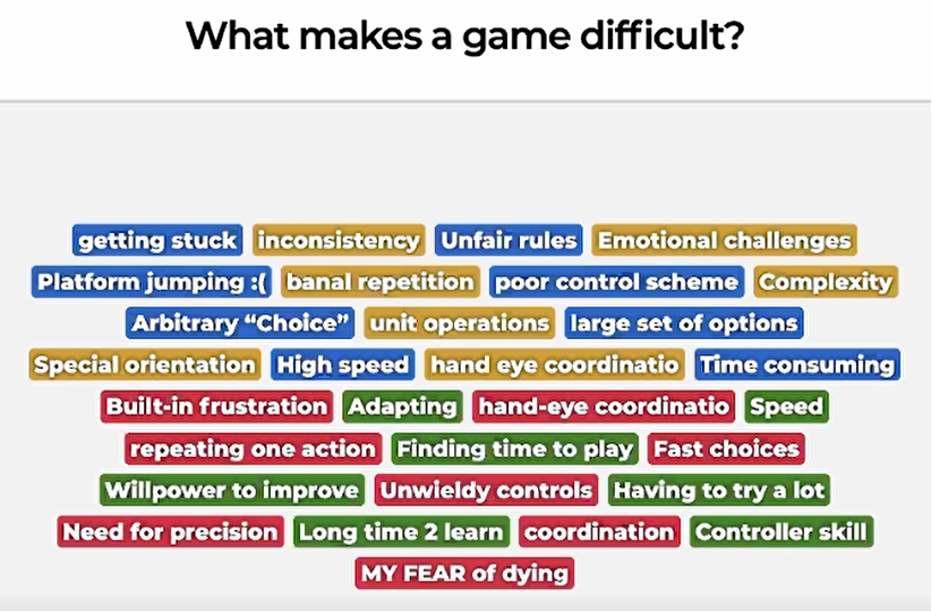

In Experimental Games, Jagoda discusses three sorts of difficulty: mechanical difficulty, affective difficulty, and interpretative difficulty. When audience members were asked the question, “What makes a game difficult?” on Kahoot, a majority of the respondents provided examples of mechanical difficulty in games, like “inconsistency,” “platform jumping,” “poor control scheme[s],” and a “need for precision.” Jagoda described them as “basically things that involve difficulties with hand-eye coordination, difficult enemies, [and] unforgiving numbers of extra lives.” To boil it down to its essence, mechanical difficulty manifests in a “physical sort of way.” Many other respondents provided examples of affective difficulty, like “emotional challenges,” “fear of dying,” “willpower to improve,” and “banal repetition” (in other words, boredom). Affective difficulty, Jagoda explained, encompasses “experiences of boredom, curiosity, complicity, uncertainty, and in some cases these intensities can be difficult to encounter.”

Too often, players think of a game’s mechanical difficulty or affective difficulty rather than its interpretative difficulty. In fact, nobody in the audience provided any examples of interpretative difficulty, even though, as Jagoda pointed out, the storylines of many art games and independent games are difficult to interpret. One may read a novel or an informational text like an encyclopedia and say, “That was difficult,” but Jagoda finds that “people tend not to use that kind of language in a nuanced way around games.” He encourages people to see past the physical and emotional challenges, to also see the message the creator is trying to get across, or even to learn lessons from a game that the player can independently discover.

At the core of Experimental Games is the question of how games can affect not only our virtual lives but also our real ones. “There’s a real value in games that raise complex problems and make problems that didn’t previously exist, which seems like a bad thing, but I argue [that it] is a very good thing,” Jagoda said. To him, game designers are mad scientists, cooking up unlikely scenarios and observing people’s gut instincts when put under extreme pressure and given a series of binary choices.

The way Jagoda uses “experimental” in his book doesn’t merely refer to a subset of avant-garde games. As a mad scientist (a.k.a. game designer) himself, he uses the term in the sense that one would in a laboratory: He sees games as sandboxes that are useful for playing with future realities and believes that these controlled digital environments can yield important information that could influence which of those potential realities we choose. “Hypothesis generation and hypothesis testing are not the province purely of the sciences, but do play out in the arts in a number of different ways…. I really think of games as artificial constructions that nudge and modulate reality’s potentials…. If we only understand better how it is they do that with computation as a component, then there are better directions we can go with game design in the next 10 to 50 years.”