In June 2020, Marie Berg, a lecturer in the French department, received an email from the Office of the Provost, sent to all of UChicago’s teaching staff. The email said that while teaching fall courses in person was strictly voluntary, “we believe strongly that in-person interactions between students and instructors in a safe setting profoundly enrich learning and the student experience.” Berg agreed with the sentiment and she signed up to teach three in-person classes in the fall.

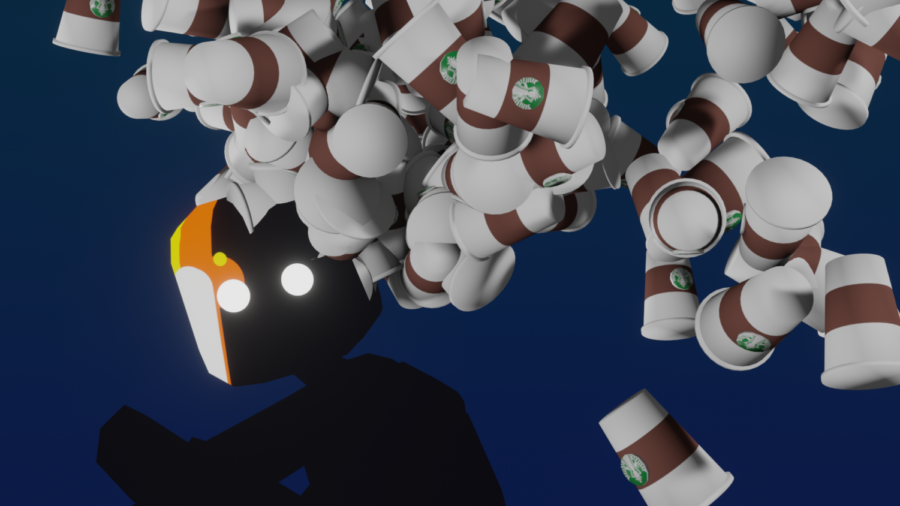

When she and a handful of other colleagues began teaching, however, they quickly ran into a problem: they didn’t have access to office space where they could safely prepare for or spend time between classes. Harper Cafe was used for this purpose at first, but reservations had to be made daily, and it did not open until 9:30 am, too late for her 8:00 am class. Eating was also not permitted. So Berg was forced to get creative.

“Last week, I worked in my car. That was not cool. It’s one main reason that makes me hesitate to teach again in-person in the winter,” Berg wrote in an email to a supervisor on October 20. “I was lucky to find a spot on University [Avenue], so I could catch the Wi-Fi from my car.”

UChicago Faculty Forward, the union that represents lecturers, raised the issue at their quarterly meeting with University representatives, but the responses they received never fully addressed the issue, union members said. At one point, University administrators told the handful of affected lecturers to “eat discreetly” in Harper Café, where eating was officially forbidden at the time; at another, administrators proposed Logan Center as a preparation space, a location far too distant from the main College quad to be a viable option during the short breaks the lecturers had between classes.

Months went by without an adequate solution and lecturers continued to lack office space—a provision which, per Article 18 of their union contract, UChicago is contractually obligated to provide.

“I felt that I was supporting the effort of the University to welcome the first-year students and the desire to have somewhat of a campus life,” she told The Maroon. “It was as if it was annoying that I had accepted to teach in person.”

It wasn’t until winter quarter, six months after the union first raised the issue with UChicago administrators, that the University arranged for the three remaining affected lecturers to have space to prepare and eat. At this point, many others had already informally arranged to use the unoccupied office space of tenured faculty members.

The University’s inability to solve such a simple issue bewildered Berg and her colleagues. They all agreed it was not malicious, and more likely, in the words of humanities Core lecturer Geoffrey Rees, just “a bureaucracy not being able to solve a simple problem.”

Regardless of its cause, the incident reinvigorated many union members’ concerns with the University’s operations, including a lack of open communication, increasingly centralized University governance, and a sense of being taken for granted—concerns that predate the pandemic.

Dysfunction in Communication Channels

Faculty Forward Network is a nationwide union representing non-tenure-track faculty members. UChicago’s chapter was founded in 2015. One of its first major victories was the creation of a promotional hierarchy in its first union contract, and, more recently, the University exempted all members of the union’s parent organization, Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 73, from the salary freeze announced at the onset of the pandemic.

Rees, a member of the union’s bargaining committee, said that, on the whole, the relationship between Faculty Forward and UChicago is “productive.” He and other union members gave the University administration credit for its skillful handling of the transition to remote learning and the flexibility it offered instructors when resuming in-person learning.

However, in his experience, the formal avenues of communication between the union and the University have often proven ineffectual.

“Some individuals were able to work out solutions by being in contact with some administrators. But most individuals were not…The official channels of communication didn’t produce any results,” Rees said. “This [prep space issue] was just a really vivid instance in which the lack of more open channels of communication caused unnecessary problems and got in the way of us doing the jobs that the University asked us so much to do.”

Currently, there are two main avenues for formal union-University communication; first, the two organizations meet at quarterly Labor Management Committee (LMC) meetings, in which five union representatives meet with five total University lawyers and administrators. The union also communicates with UChicago through a representative from SEIU, who passes their communications along to lawyers in the Provost’s office. But dysfunction in these official channels has often caused union members to seek informal ways to address their concerns, as in the case of finding preparation space this past year.

The theme of open communication recurred over the summer when the union sent a letter to the Office of the Provost requesting additional details about the University’s reopening plan. This included queries about COVID-19 testing, ventilation, access to indoor spaces between classes, and other issues. While University staff were in contact with union representatives throughout the fall, they received no formal response to this letter, noting that some of these concerns such as access to preparation space were not resolved for several months.

“Second Class”: Remoteness from Power in University Governance

Several members diagnose the union’s struggles as a symptom of two interrelated, decades-long trends in academia.

The first is the erosion of shared governance and the consolidation of power in universities’ central administrations—a trend that defined the tenure of former UChicago President Robert Zimmer. In 2019, over 100 professors wrote to University administrators after UChicago announced cuts to its doctoral programs. The letter called the move “a purely top-down, non-consultative imposition of a comprehensive transformation of the structure and substance of academic life in this university,” and a “betrayal” of the principle of faculty governance.

Stephen Haswell Todd, a humanities Core lecturer and member of Faculty Forward’s steering committee, believes that this trend contradicts the University's values of free intellectual exchange.

“One thing that the pandemic has brought out, but that also precedes the pandemic and is independent of it, is an increasingly stark contrast between the official University values of free speech, critical thinking, and intellectual exchange…and the utterly hierarchical, bureaucratized, opaque structure of University governance that makes those very conversations structurally impossible for us to have with other parts of the University,” Haswell Todd said.

The second trend complicating the union’s goals is universities’ growing reliance on non-tenured instructional staff—what has been called the “casualization” of academic labor. Several decades ago, tenure-stream faculty members constituted the vast majority of academic appointments; now, an estimated three quarters of new faculty hires nationwide are off the tenure track. Non-tenure track labor is appealing to universities as it is generally cheaper and more flexible than tenured positions, though the lack of tenure makes positions significantly less secure for the faculty occupying them.

Despite the University’s increasing dependence on them, only tenured faculty members are represented in UChicago’s faculty governing body, the Council of the University Senate. This is not the case at all universities; many do represent full-time, non-tenure-track faculty, and some also represent part-time ones.

University spokesperson Gerald McSwiggan wrote in an email to The Maroon that representation on the University’s governing bodies is defined by “longstanding University statute.” These statutes specify that “Professors, Associate Professors, and Assistant Professors who have completed one year's full-time service on academic appointment at whatever rank” are represented on the Council of the University Senate.

But many union members read the lack of representation as a sense of being taken for granted by the central administration.

“The view of the administration [is] that ‘you’re not really that important, not really significant,’” said Dmitry Kondrashov, a member of the union’s bargaining committee and an instructional professor in the Biological Sciences Collegiate Division. “That sticks with a lot of us as their attitude…This notion that you are lesser is always there.”

Per University statutes, lecturers are technically designated “other academic appointees.” Several union members said that the symbolic importance of this label is telling.

“The University will not even dignify us with the name ‘faculty,’” Kondrashov said. “We call our union ‘Faculty Forward,’ but they will not even acknowledge that we are faculty.”

“One’s job title shouldn’t matter in regards to who can be a part of the conversation,” Rees agreed, noting the importance of representation in the University’s governing bodies.

Reached for comment, McSwiggan wrote in an email to The Maroon that “academic appointees are valued members of the University community and are extremely important in fulfilling the educational mission of the University.”

The union’s four-year-long contract expires on April 30, 2021. Negotiations for the new contract are ongoing.