On November 13, 1968, sociology professor Marlene Dixon stepped out of line.

On November 13, 1968, sociology professor Marlene Dixon stepped out of line.

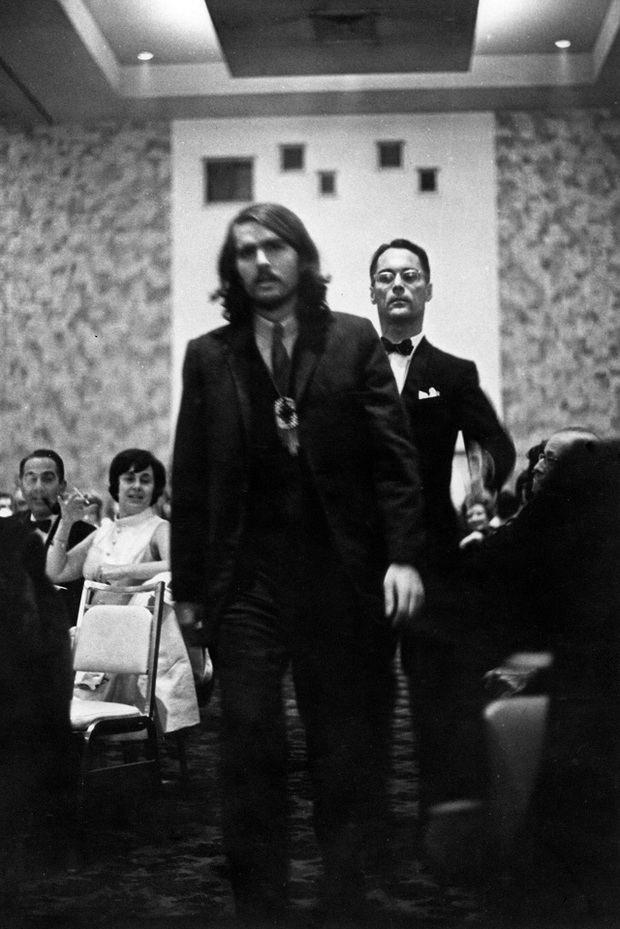

During a faculty procession at the inauguration of Edward Levi, the University’s eighth president, the openly Marxist and feminist Dixon opted to stand alongside the 100 students chanting “Work, study, get ahead, kill!” outside the main entrance of Chicago’s Conrad Hilton instead of entering the hotel with her colleagues.

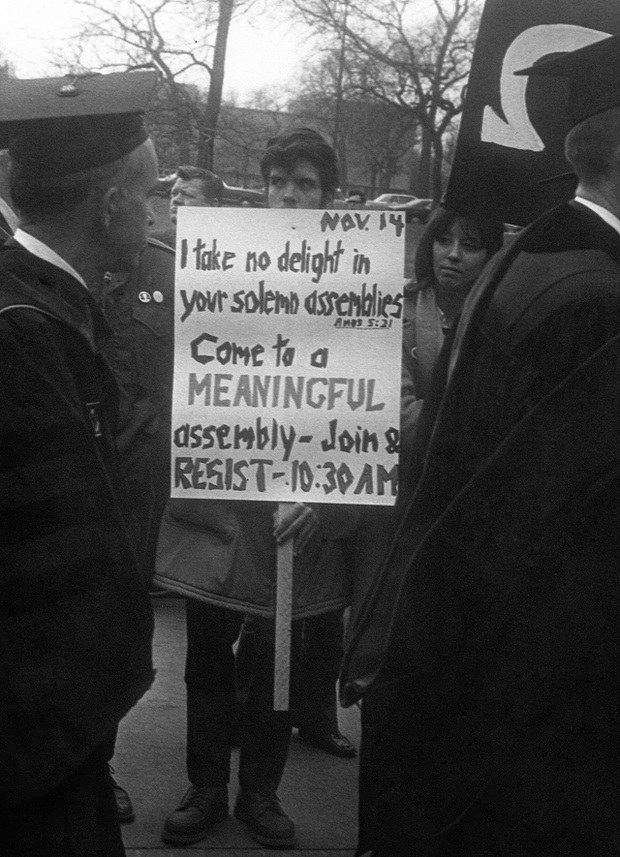

Two months later, when the sociology department unanimously declined to renew her appointment for a second term, some students recalled Dixon’s earlier show of solidarity. In early January, students banding together as the Committee of 75 sent an open letter to the Maroon, demanding that Dixon be rehired and that students be given an equal say in decisions to hire and fire professors.

In the days that followed, the Committee of 75 became the Committee of 85. By the end of the month, it had swelled to the Committee of 444.

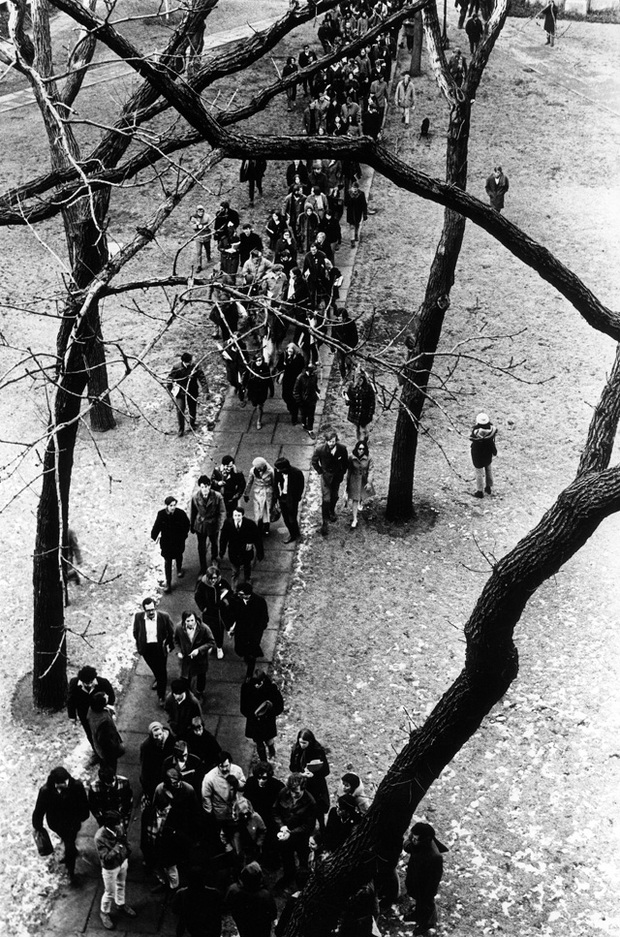

And the group voted to do more than picket and petition. Before the month’s end, the students made their move—over 400 of them overtook the Administration building and refused to surrender for two weeks.

Yet awareness of this story is mostly limited to its eyewitnesses. The University of Chicago’s 1969 sit-in—and the record-breaking 42 expulsions that followed it—has not even a Wikipedia page to call its own.

Stranger still, this two-week takeover is nearly absent from the collective memories passed down to each new generation of students, leaving a vacant seat next to tales of Leopold and Loeb, urban renewal, and Hyde Park homicides. But for the students and faculty who remember the sit-in as its 40th anniversary approaches, the event remains an indelible moment in the University’s life story.

Students stand up—or sit down—to the administration

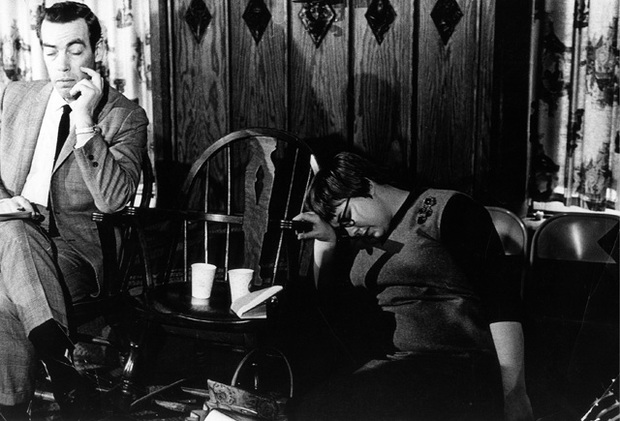

When student protesters occupied the Administration building at noon on January 30, private offices were locked and phones were dead. Administrators had readied the building for a takeover.

On one office door a sign read, “Sit-inners: Water my plants if you’re here Friday. They’ve already been watered Thursday.”

The students were also prepared for the protest. They had already had some experience in mass demonstration. May 1966 saw a three-day shutdown of the Administration building by 450 students protesting the University’s Vietnam War draft policy.

Earlier protests had primed the administration’s defenses against such disruptions. Though no disciplinary action followed the 1966 sit-in, the Council of the Senate, a faculty body, recommended “appropriate disciplinary action, not excluding expulsion” in dealing with future disturbances.

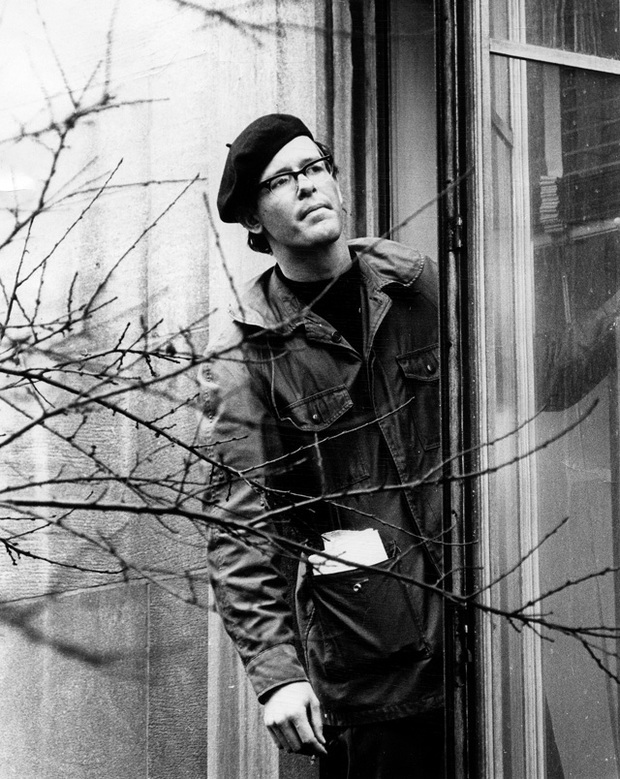

Sure enough, 58 one- and two-quarter suspensions followed a second sit-in in 1967. But the punishment hardly deterred students like Howard Machtinger, a sociology graduate student and member of the radical activist group Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

“I traveled around—I went up to Stop the Draft Week at Berkeley,” said Machtinger, now retired after a career in education. “I got a chance to be the SDS delegate to the Bertrand Russell war crimes tribunal in Copenhagen.”

And while national issues from civil rights to Vietnam to the women’s movement galvanized students across the nation, Machtinger said activism at the University found a focal point in local questions, including the University’s campaign for urban renewal.

“There was a notion among students that the University was really removed from the larger issues,” he said.

Marlene Dixon: The face that planted 400 sitters?

In spite of efforts by SDS and other groups to call students to action, a protest like the sit-in could not have erupted without a catalyst.

That’s why classics professor James Redfield, then the founding master of the New Collegiate Division and associate dean of the College, calls the controversy over Marlene Dixon’s reappointment “a gift” to the activists.

“I watched SDS for two years trying to find their issue, and they finally settled on this one,” Redfield said. “They should have known that that was the issue they would get the least faculty support on.”

The alleged link between Dixon’s political beliefs and her dismissal seemed shaky to many faculty. On February 12, sociology professor Edward Shils released a scathing 10-page critique of the research Dixon had produced over the past three years. Others, like Redfield, suspected Dixon’s popularity with students came more from her Marxist leanings than her teaching abilities.

For the protesters, however, these issues were secondary. The discharge of a popular and radical teacher fed existing student concerns that their role in University governance was negligible and that perhaps the administration cared more for the school’s academic reputation than for the quality of students’ experiences.

In an e-mail interview, Wendy Kates (A.B. ’71), a former Maroon staffer, said she felt that Dixon served as a rallying point for students.

“I do think that Marlene Dixon symbolized several important issues for many of the students, including the underrepresentation of women in the University, the University’s unwillingness to hear input from radical thinkers on campus, and the extent to which the University…in the name of ‘value-free social science’…not only separated itself from many of the social problems of the day, but also may have contributed to some of those problems (e.g., through its relationship with Woodlawn),” Kates said.

Kates also believes, however, that Dixon’s dismissal presented an opportunity for angry students to unite—regardless of the disparate reasons for their ire.

“I think that a sizable portion of the students in the sit-in participated because, like many children of the ’60s, they felt angry at ‘the system,’” she said. “I think that they would have participated in the sit-in regardless of the specific issues that sparked it.”

Redfield agreed that the sit-in drew students for more reasons than meet the eye.

“There are people who are ideologically committed,” Redfield said of the attendees. “There are angry people. And there are guys who are picking up chicks.”

Sitting pains

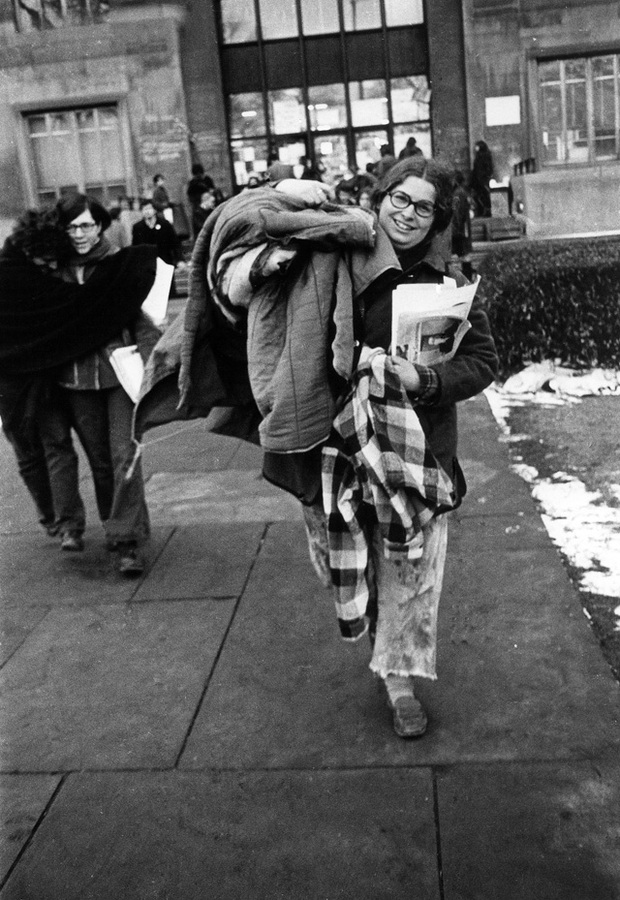

Sitting, it turns out, was harder than it sounded. One of Kates’ Maroon articles featured a sitter named Lynda who had been suffering alternately from constipation and diarrhea for six days.

“Woodward Court food may be greasy, but at least it’s somewhat nourishing,” Lynda said in the article. “Here we have peanut butter for breakfast every morning.”

Machtinger, one of the sit-in’s main leaders, agreed that the protest was grueling.

“It was exhausting,” he said. “People were very tired, and tactics of the administration to wait us out were hard ones to work with.”

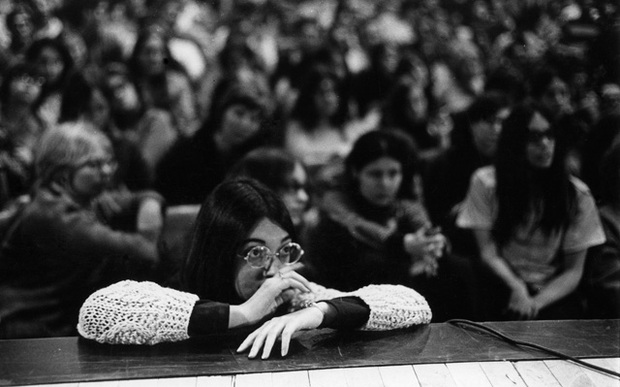

At the same time, the sit-ins featured some of the best of ’60s culture. Throughout the Administration building students played music and held political meetings, including a sizable women’s caucus.

“Especially for the first week and a half, it was a kind of heightened experience,” Machtinger said. “Like a lot of sit-ins of that period, it had a glimpse of something a little less alienated at the time than campus life.”

Machtinger half-expected his own expulsion. He met the prospect of punishment with a kind of nonchalance.

“The day of our disciplinary hearing, a few of us went to play basketball in the gym with a female student,” Machtinger said. “And they tried to kick us out because they wouldn’t allow women to play in the gym. Well, we said, ‘What are you going to do to us? And they said, ‘You might get suspended.’”

Since he and his companions were already boycotting the disciplinary hearing, they decided suspension wasn’t much of a threat. They played ball.

Not all protesters, however, could shrug off their academic prospects as a necessary casualty of their activism.

“When people talk about the ’60s, they sometimes talk about it as if everyone wanted to go out and get arrested, or get expelled,” Machtinger said. “But in fact many people felt they were risking some of their life’s chances….It was not a light decision.”

Tiffs and a typewriter

The largely nonviolent protest had some flareups, including an anonymous bomb threat to the Administration building. And when non-University intruders faced off with students in the lobby, one intruder threw a typewriter across the office, and a student security guard was knocked down and hit in the face with a broom handle.

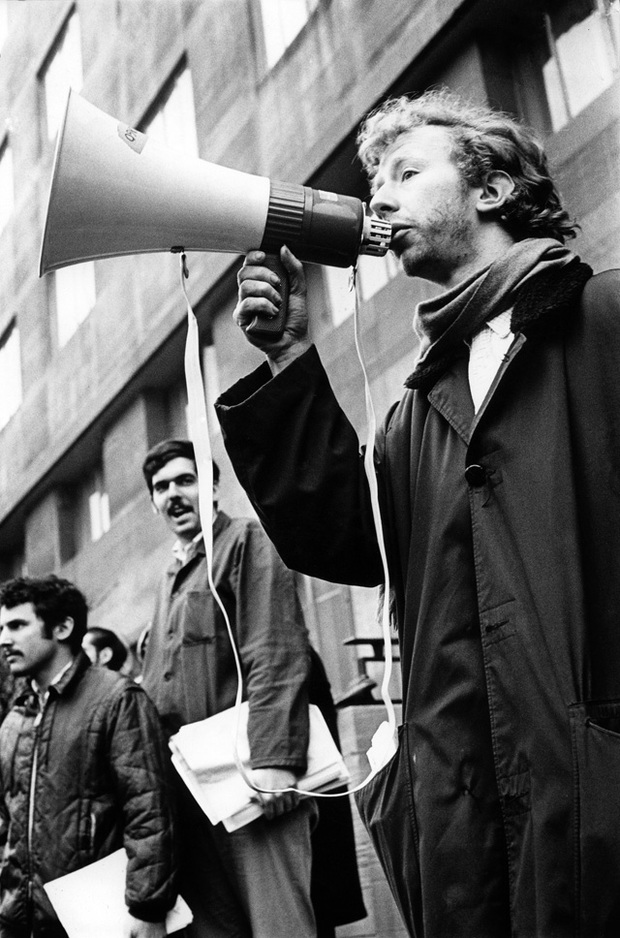

The tensions did not dissipate when the sit-in ended. An SDS–led protest against the Disciplinary Committee in front of Levi’s house in late February was dispersed by campus police after students kicked through the president’s front door.

Another student group, calling themselves the “Chickenshit Brigade,” also dedicated themselves to harassing administrators. On February 5, 30 Chickenshits surrounded the Quadrangle Club, tooting on kazoos, tapping on windows, and chanting “61”—then the current number of suspensions announced by the Disciplinary Committee.

“You’re all very badly in need of psychiatric care,” said Julian Levi, an urban studies professor and brother of President Levi, to the protesters when he emerged. He then pointed at the students, shouting “62,” “63,” “64.”

However, the protesters’ aggression proved to be counterproductive. Not long after the incident at the president’s house, Redfield attended a sherry hour at the former residence hall Woodward Court. He came outside to find a mob waiting for him.

“It was scary,” he said. “They all crowded along with me, so I thought I’d take them to Jimmy’s and let Jimmy’s call the police. But we didn’t get that far; we kind of got bogged down. So this so-called ‘Jamie Redfield incident’ made Newsweek; it was all over the place. And that cost them a lot of good will.”

While uninvolved students largely supported disciplinary amnesty for the protesters, faculty opinion varied widely. Some, like Redfield, spoke on the behalf of several students at their disciplinary hearings. Others found themselves on the side of Milton Friedman, who held a press conference in vehement opposition of granting amnesty on the seventh day of the sit-in.

Though President Levi faced great pressure to call the Chicago police during the sit-in, some professors remain grateful to this day that he kept his cool.

“There were so many bad examples already, and there were ones afterward, out of Berkeley [and] Harvard, where administrations overreacted,” said David Bevington, an English professor emeritus. “I was very proud of the University—it set a very moderate, legal, procedural way of dealing with an extraordinary event.”

The absence of a final showdown between students and law enforcement may be why the sit-in remains little-known today. The University’s 1969 sit-in, while rife with tensions, ultimately was an imperfect storm.

“The whole thing builds to the police raid,” Redfield said, describing the ideal media-ready college protest. “That’s the big scene, and when that doesn’t happen, they don’t quite know what to do.”

Leaving their seats

In the early ’70s, Redfield drove through Green River, UT, to visit Wayne Booth, who retired from his post as dean of the College in 1969. In the middle of the desert, Redfield stopped at a general store to refuel.

“So the guy’s pumping my gas, and I’m stretching my legs, walking up to the post office,” Redfield said. “And there’s one of my students, on the post office wall, wanted for arson.”

Expulsions did not stop former students from pursuing further activism, whether through legal or extra-legal means. Machtinger was one of many who joined the Weather Underground, a radical leftist group.

Though the students continued the struggle for change, their demands on the University remained unmet. The sit-in ended after a secret meeting at the East 53rd Street YMCA in the second week of February between Machtinger and another graduate student leader, and Julian Levi.

“They basically wanted me to stop the sit-in, but they weren’t really responsive to any of the demands,” Machtinger said. “So I felt like I was supposed to be awed by the experience, but nothing substantive was offered.”

On February 12, a president-appointed faculty committee released its report, recommending a one-year appointment for Dixon in the Committee on Human Development—but not in the sociology department. Dixon refused the appointment and left for McGill University the following year. On February 14, when the sit-in finally drew to a close, no party involved was wholly satisfied.

But in the weeks, months, and years that followed, concrete steps were taken to remedy aspects of campus life that both activists like Machtinger and more moderate students like Kates found alienating. The creation of an ombudsperson, the restructuring of the Reynold’s Club as a student center, and the implementation of course evaluations all have their roots in the 1968 –1969 school year.

Though the sitters demands for equal say in faculty hiring and firing decisions never materialized, several departments now have undergraduate and graduate committees, and include graduate students on search committees for new faculty.

As the sit-in’s 40th anniversary approaches, it serves as a reminder that the University has come a long way, yet remains a work in progress. An editorial in the April 1, 1969, edition of the Maroon may have a familiar ring: “Walk up to any College student at any time, ask him how he feels, and three times out of four the answer will be, ‘Miserable’…. Students feel remote from their faculty, cut off from other students.”

Perhaps the sitters’ legacy is their belief that change to the University can come from the ground up. Bevington feels the clashes and compromises of 1969 instilled an impulse on campus to improve University life.

“In the upshot I think it was very good, not only in that things calmed down and people went back to classes, but in that the reform movements that were set in motion continued—and not just during the occupation or in the few days afterward,” Bevington said. “This was something that had a momentum all of its own.”