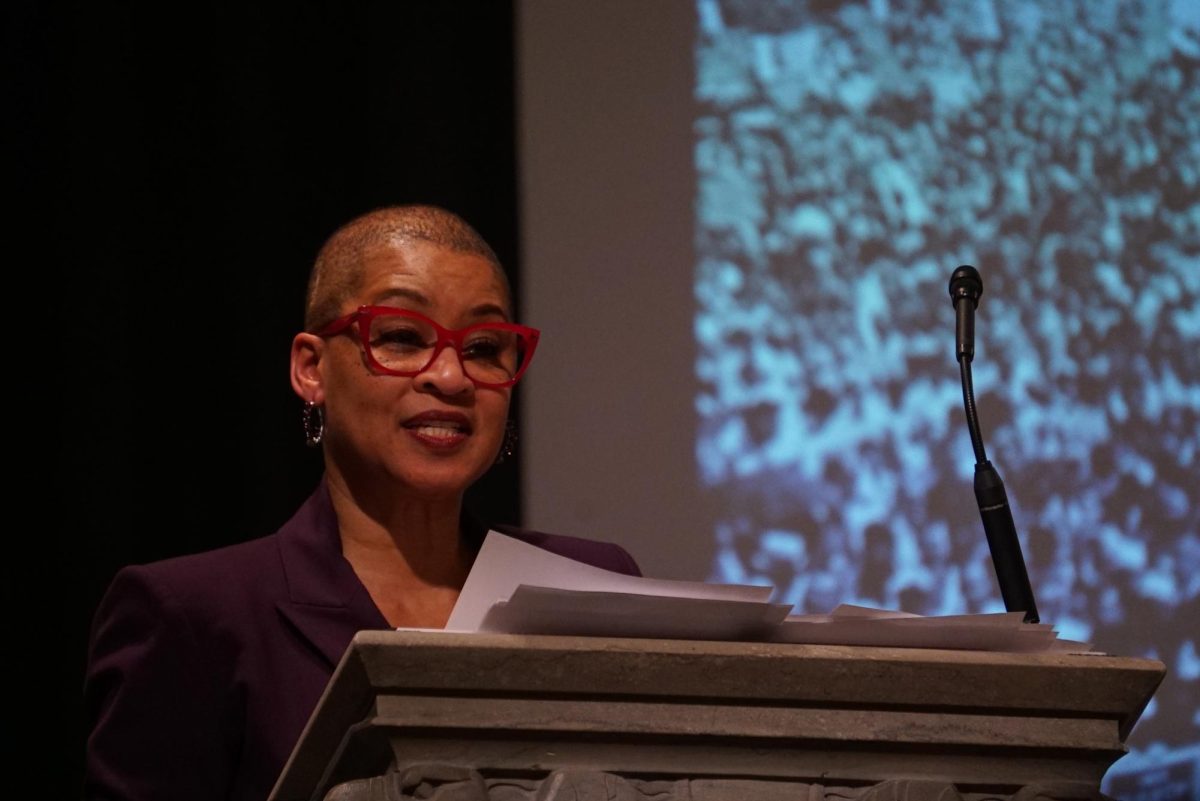

On April 21, Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield, the new United States ambassador to the United Nations (U.N.), sat down with IOP Director David Axelrod for a live taping of his CNN podcast, The Axe Files. Axelrod and Thomas-Greenfield’s conversation covered her many years spent abroad and how she sees the U.S. position on the world stage as very significant due to these experiences.

Thomas-Greenfield, who was nominated for the position by President Joe Biden and confirmed in a 78–20 Senate vote in February, served in multiple positions as an Ambassador to Liberia and the Director General of the U.S. Foreign Service. She resigned from her most recent office as the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs in 2017 during the Trump administration over disagreements with Trump-appointed leadership of the department but returned from retirement in 2020 as a member of President Biden’s Agency Review Team to support transition for the State Department.

Thomas-Greenfield will be just one of three Black citizens, and the second ever Black woman, to serve as the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N.

Thomas-Greenfield recalled learning about the Peace Corps as a young student before serving in the agency, describing how it shaped her and other Black students’ understanding of the international stage. “[Experiences as part of the Peace Corps] open up so many doors of our minds; I had never even heard anything about Africa, whatever we heard about Africa was Tarzan,” Thomas-Greenfield said. “We hadn’t experienced the real Africa. We hadn’t experienced the real people of Africa, and Peace Corps brought that to our community.”

But the Peace Corps didn’t just provide an understanding of the international stage: It challenged the discriminatory status quo of the day and of the American foreign service. “[African Peace Corps members] insisted that they be allowed with their African features and with African Americans to use the local washateria that had a ‘for whites only’ sign on the front door, they insisted on going into restaurants,” Thomas-Greenfield said. She added that this “opened doors for [Black people in her community] that we ourselves never thought could be opened, and I have always been thankful for that experience.”

This effort to combat racial discrimination stayed with Thomas-Greenfield as she spoke at length about the need for diversity in the foreign service, referencing a trip she made to Rwanda during the Rwandan genocide in 1994. She detailed how she was mistaken for a Tutsi woman and held at gunpoint until she could prove her American nationality and diplomatic status.

“I lived to tell the story,” she said, but she emerged with one important lesson: “they didn’t know that I was an American diplomat because they’re not used to seeing a Black diplomat,” Thomas-Greenfield said.

When asked about her reaction to the jury finding Derek Chauvin guilty for the murder of George Floyd in relation to her remarks on the legacy of racism in the United States, Thomas-Greenfield noted the suspense building up to the decision. “I didn’t know what to expect, I didn’t know whether justice would be served, and that is the experience that so many African Americans experience,” she said.

Thomas-Greenfield faces the tough task of reintegrating the U.S. into the global community after the Trump administration reneged on prior international commitments and pursued an isolationist foreign policy. This task is especially important since the U.S. assumed the Security Council Presidency in March, which means that she would take point on agenda setting and policy disputes for the council.

Thomas-Greenfield spoke of the importance of regaining the trust and engaging with political adversaries and allies. “It’s a challenge…I think that everything we’ve done in the 100 days of the Biden administration shows that [the United States is] back,” she said.

Within the first month of the Biden administration, the U.S. rejoined the Paris Climate Agreement and the U.N. Human Rights Council and backtracked on the decision by the Trump administration to withdraw from the World Health Organization.

When asked by a member of the audience about the U.S.’s stance in Africa regarding Chinese involvement, Thomas-Greenfield said “I tried to explain that, but I got myself in trouble but I do think we should be partnering with African countries…so they can get better deals out of the Chinese,” walking back on her previous comments regarding China and Africa that drew criticism during her confirmation hearing. Thomas-Greenfield previously gave a speech at Savannah State University’s Confucius Institute calling cooperation between the U.S. and China in Africa a “win-win-win situation,” something that was seen by some senators to be to be soft on the intention of Chinese policies in the African continent.

After teaching political science at Bucknell University, Thomas-Greenfield left and joined the foreign service in 1982 as a consular officer at the US embassy in Kingston, Jamaica. She described her decision to join the foreign service as one “that made a lot of sense” upon realizing that a career in academia was not her passion.

“The advice I can give you is: do it,” Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield said to audience members looking to pursue a career in foreign service. “I have not had a single regret coming into the foreign service, 35 years of joy for me,” Thomas-Greenfield said, adding that all of the hardships of the job were something she found “empowering.”