Chicago Public Schools (CPS) announced this January that 30 public schools would be renamed in order to avoid endorsing problematic historical figures, such as those who owned slaves or expressed bigoted thoughts. In San Francisco, public school names are already in the process of overhaul, as many believe that naming a school after a questionable political figure acts as an endorsement of their views. Washington High School is one of the schools that’s now set to be renamed by the San Francisco Board of Education (SFBOE). Their reasoning is that George Washington, the school’s namesake, was a slaveholder—and that’s fair enough. But when you start to put historical figures on trial, nobody is innocent—moral purity and greatness rarely go hand in hand. What’s critically important is that we do not erase or discount the importance of symbolism’s ability to spark critical thinking just because it’s nearly impossible to find a historical figure not tainted by something problematic. CPS should avoid being as unnecessarily judgmental as the SFBOE has been.

Lincoln High School (named after President Abraham Lincoln, the ally of abolitionists and leader of the Union during the Civil War) is also set to be renamed, with the committee citing his response to the Sioux uprising as sufficient basis. In the wake of an attack on white settlers on Dakota lands, approximately 300 Dakota tribesmen guilty of participating in the attack were going to be executed. Presidential approval was required. In the end, 38 Dakota men—those who had committed murders determined not to be in self-defense—were executed, because President Lincoln reviewed each person’s case individually rather than punishing the entire group. Because Lincoln signed off on the execution of Native Americans, an historically oppressed people—regardless of the fact that the particular individuals, race not considered, had actually committed the crimes they were executed for—his name will no longer grace the San Francisco high school.

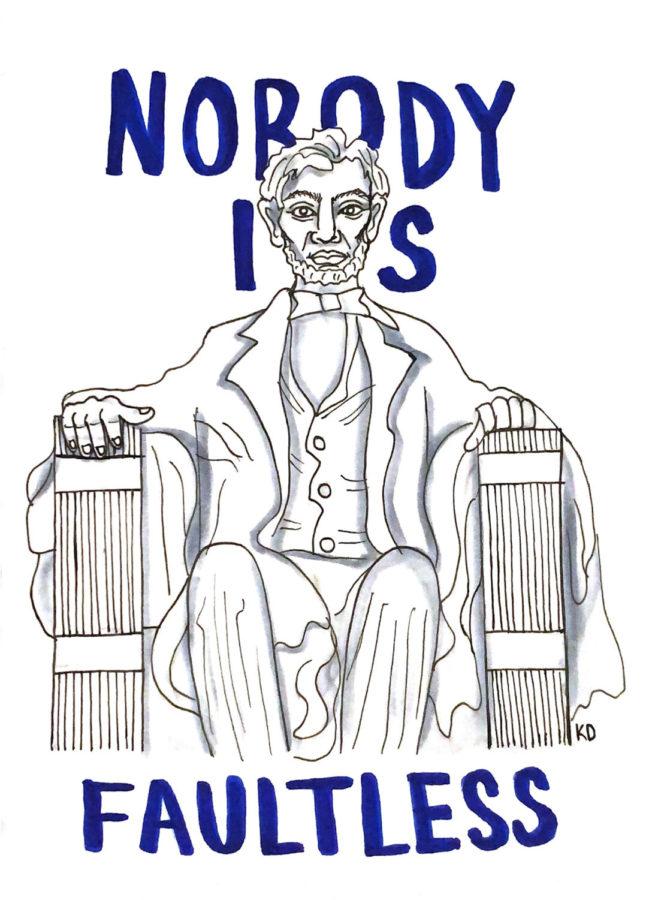

If we follow this reasoning—that any president who has approved of the execution of criminals (who are often societally oppressed individuals from poor upbringings, just like the Dakota tribesmen who were executed) is indirectly a murderer—then all of our presidents have been murderers, including President Barack Obama, who is considered perhaps our most progressive president to date. Hell, by being Commander-in-Chief of the American military-industrial complex, every president has indirectly condoned murder. Like I said, moral purity and greatness rarely go hand in hand. No one is completely faultless. Regardless of their inevitable imperfection, we need leaders, and we need to remember the legacies of leaders in our past.

We need to ground our perceptions of historical leaders and the importance of what they represent in actual fact, whether that fact puts the leader in a good or bad light. Finding fake imperfections when people are already imperfect enough is making it hard to appreciate those instances where humanity has succeeded. For example, the committee involved in the San Francisco renaming process decided to rename Paul Revere High School because they wrongly assumed that the purpose of the Penobscot Expedition that Revere took part in was to colonize the Penobscot people, when the true purpose was to resist British imperialism by attacking a fort. This was an assumption based on the name of an event and was apparently made without any further research. Perhaps the sensible method to prevent misinformed judgments from a committee of public school officials without history degrees and without any sort of counseling from a historian is not to provide them with the aid of a historian, but to eliminate the need to name schools entirely. How about we go by a numbering system? Then nobody can be offended! After all, it’d only be a number. Just like how nobody can be offended by a white wall instead of a mural. Just like how nobody can be offended by a blank page in a book. Just like how nobody can be offended by school uniforms that strip the identity from the students who wear them. When naming institutions after historical figures, important symbolism speaks to key moments in our history. Without such symbols, we are left with a landscape devoid of history and reminders of past failures. I believe that it’s better to acknowledge our past failures in order to avoid recurrences by keeping these symbols rather than getting rid of them and erasing them from our minds.

Of course, canceling these titans isn’t the only goal of groups like SFBOE and CPS. They also want to spotlight the unsung heroes of history. That’s great, but often very difficult to achieve. Unfortunately, there isn’t enough biographical information on most historical figures who were parts of marginalized groups. This has been a major contributing factor to the cultural and ethnic homogeneity of school names. Marginalized people are frequently no more than a name in history books, while the affluent white male group which, for the most part, wrote and recorded American history, have chapters and chapters on their accomplishments and lives. People who did great things have been denied true greatness: the kind of acknowledgement and memorability that typically white, male historical figures have. The names of those who were marginalized in the far past simply do not hold the same symbolic weight as historical figures who were part of the white male majority, due to a lack of substantive biographical information about them. The people whose names have the most symbolic weight may not have been the best people, but they are the ones we remember and have the strongest associations with various societal failures and successes. It’s more important to remember history than honor suppressed individuals with no recorded history. This is why these names shouldn’t be erased and replaced with less well-known ones, because no matter how much research is done, there is still a dearth of information to uncover and without the power of genuine symbols, we may forget what happened. History is recorded by the group with power, even when they don’t wield that power for good. Hence, we often don’t know anything deeper than a name and a scant number of biographical facts for less famous historical figures of marginalized groups.

The most important thing, regardless of whether we’re celebrating our successes (which we don’t do often enough), or acknowledging our failures (which we also don’t do often enough, though certainly we focus more on our failures than successes), is to make sure that symbolism prevails, in whatever form it takes, be it a name on a school, campus building, or monument. Symbolism provokes thought, and can lead to learning. Erasing these forms of expression should be avoided at all costs.

As the Chicago Public School Renaming Committee selects which 30 public schools will have their names changed, and which names will take their place, they should take into consideration the fact that nobody is faultless—not even Abraham Lincoln. This doesn’t mean that we have to start renaming everything honoring him or rewriting history. This is good news for the capital of Nebraska. Learning from the mistakes of the San Francisco public school renaming committee, CPS needs to do its research and bring in historical experts to validate the reasoning behind changes that will hold a lot of symbolic weight. Does the good this person has done outweigh the bad? Beyond this, the committee should ask itself: How much history does this name hold? What can we learn from their lives? If it were up to me, CPS wouldn’t be renaming these schools at all. The names of these particular figures were chosen to grace the faces of these schools in the first place because they had historical significance, not because they were perfect. Reminders of a troubled history are not an endorsement of what has passed, but rather a reckoning with our history, both good and bad.

Emma-Victoria Banos is a first-year in the College.