Associate professor of cinema and media studies Allyson Nadia Field spoke on the depiction of African American affection in early American cinema through the investigation of a nitrate film print dating to around 1900 from William Selig’s “Something Good—Negro Kiss.” The event, “Recovering Black Love on Screen,” marked the return of the signature Harper Lecture series hosted by UChicago Alumni this quarter.

Field began her investigation of “Something Good—Negro Kiss” in January 2017 when Dino Everett, film archivist at the University of Southern California (USC), asked Field about a nitrate film print he had acquired depicting a well-dressed Black couple—a rare scene from the silent era of films. “What struck me as so extraordinary was not just their dress but the fact that the man and woman embraced repeatedly in a non-caricature way,” Field said. “I was taken by the apparent naturalism of their performance that seemed to go against the grain of racialized comedy of the era.”

The process of tracing the origin and history of the nitrate prints and films was difficult. Field and her colleagues went through catalog evidence to trace the film back to filmmaker and Chicago native William Selig. This helped them in their next goal: uncovering the identities of the performers. “Figuring out who the performers were was like finding a needle in a haystack,” Field said.

Field and Everett immediately went to work investigating what Field calls an “archival mystery.” The scene seemed to be a version of “John C. Rice–May Irwin Kiss,” and many subsequent iterations of “The Kiss” short film were created in early cinema with different performers.

Collaborating with the curators at the Museum of Modern Art and their analog facial recognition database, Field and Everett were able to put names to the faces; the couple turned out to be Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown, who were part of the vaudeville entertainment quartet Rag-Time Four. The group performed different types of acts, such as the famous cakewalk dance. “Part of this work, as I see it, is restoring humanity to people mistreated by the historical record,” Field said. “I want to approach these figures with a degree of care and understanding about them as people.”

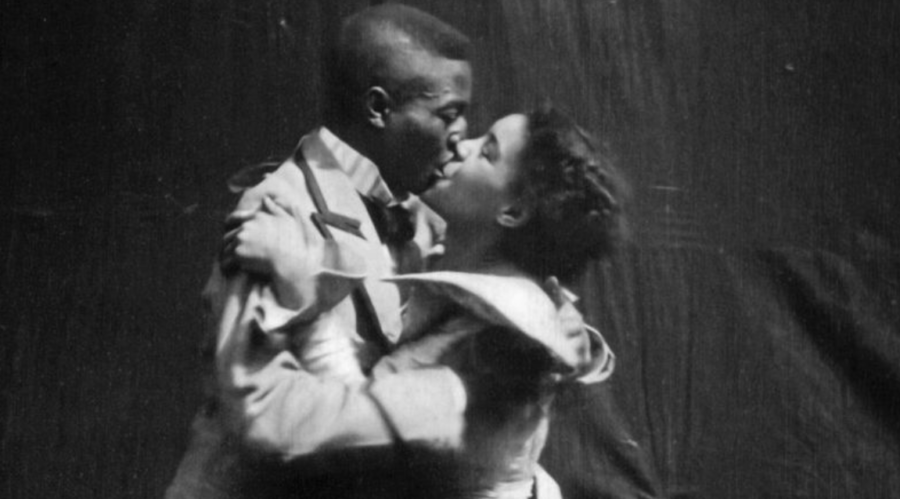

Field then played the digital copy of the nitrate print, which was restored at USC by Everett. The short black-and-white clip showed Suttle and Brown embracing playfully and kissing casually against a plain backdrop. “I think watching the film puts into stark relief the incongruity between what appears in the frame and the presumption of racialized comedy based on the descriptions of the film as a burlesque on the Rice-Irwin kiss and the arguments that film historians have made about African Americans in early cinema,” Field said.

“What makes this film so important is the way I think it quickly leads into deeper waters, making me question what I understood to be the foundations of American cinema,” Field said.

“Something Good—Negro Kiss” was sold to exhibitors as a parody of the famous Rice-Irwin kiss. Field explained why this was problematic: Irwin, a famous white minstrel performer, popularized “coon songs,” a genre that presented a stereotype of Black Americans. Irwin even adopted the persona of a threatening Black man as part of her act.

“Even though she did not perform in blackface makeup, she was a minstrel performer who traded on egregious representations of Black people,” Field said. “Seen in relation to May Irwin’s racial masquerade, ‘Something Good—Negro Kiss’ can be understood as making visible what was only implicit in Edison’s film, restoring racialized performativity to the screen and importantly refuting the racist caricature that May Irwin’s presence carried.”

Field questioned what it meant to do a racial burlesque of a film that was already racialized. “[It] places the humor not on the bodies of the African American performers whose work was presumed to be that of comedy but redirects it in a gesture of irony back to May Irwin herself. It makes overt the implicit joke of the Rice-Irwin kiss,” Field said.

African American kiss films were shown in a variety of locations ranging from opera houses to fairgrounds. Since they were so short, the films featured programs of different subjects such as the Spanish American War, comedies, trick films, fight films, and a range of other early cinema attractions, which raises the question of how the meaning of kiss films may have shifted in the context of different exhibitions. “These are the kinds of uncertainties that make [“Something Good—Negro Kiss”] rich for revisiting questions of early film spectatorship,” Field said.

After verifying the identification and dating of the film, Field and her National Film Registry, a list of historically and culturally significant films named by the Library of Congress each year. After it was added to the registry in December 2018, it immediately gained international attention, especially through social media, and spurred additional film rediscoveries, including an alternative, longer version of the film as well as a cakewalk film made with the same performers.

“While surprising especially for those of us working in the relative bubble of archives in academia, these responses also make sense. The film resonates today with contemporary representation of Black love on screen,” Field said.

These lingering responses and questions have inspired Field to pursue this work. “It’s a reminder of the imperative that film scholarship can have to witness the incredible resilience of African-American performers fighting for self-representation and for a screen image rooted not in caricature but in humanity,” Field said. “In rethinking the emergence of American filmmaking in the late 19th century, I hope to restore legibility to these films by reassessing the interrelations of forms of minstrelsy, vaudeville, and cinema at a period of really complex functioning racial tropes and early significations.”

Field is currently working on her next book, tentatively titled Minstrelsy-Vaudeville-Cinema: American Popular Culture and Racialized Performance in Early Film, for which she was named a 2019 Academy Film Scholar by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.