With its stone fireplace and wood paneling, it would be less surprising to see Indiana Jones walk into Gil Stein’s office at the Oriental Institute than the visitor who stopped by five years ago.

“Are you Gil Stein?” the man asked, standing in the doorway to Stein’s office. Stein answered in the affirmative.

“You’ve been served,” the man said, handing over an envelope. And with that, he turned and left.

The envelope revealed a summons from the federal district court of the Northern District of Illinois, demanding that Stein, the Institute’s director, turn over ancient tablets from the Institute’s Persepolis Fortification Archive and Choga Mish collection. They would be sold, according to the summons, in order to compensate victims of a 1997 terrorist attack funded by Iran.

“I was in deep shock,” Stein said. “No one had any idea how long, how complex, how many institutions would be involved, or the international impact this case would have.”

But after five years of litigation, Stein is used to the notion that these little-known artifacts have marked the convergence of terrorism, international relations, archeology, and international law—and that the Oriental Institute, which is usually more concerned with ancient disputes than contemporary diplomacy, is playing politics at the highest levels.

In it’s long life, the collection in question has endured its share of drama. The Persepolis Fortification Archive is a collection of nearly 30,000 tablets and an untold number of fragments, discovered at the Persepolis archeological site in 1933. The archive has been in Chicago since 1936, after Iran agreed to loan it to the Oriental Institute for further study. The Choga Mish collection is also on loan to the Oriental Institute from Iran, and has been in Chicago since the ’60s.

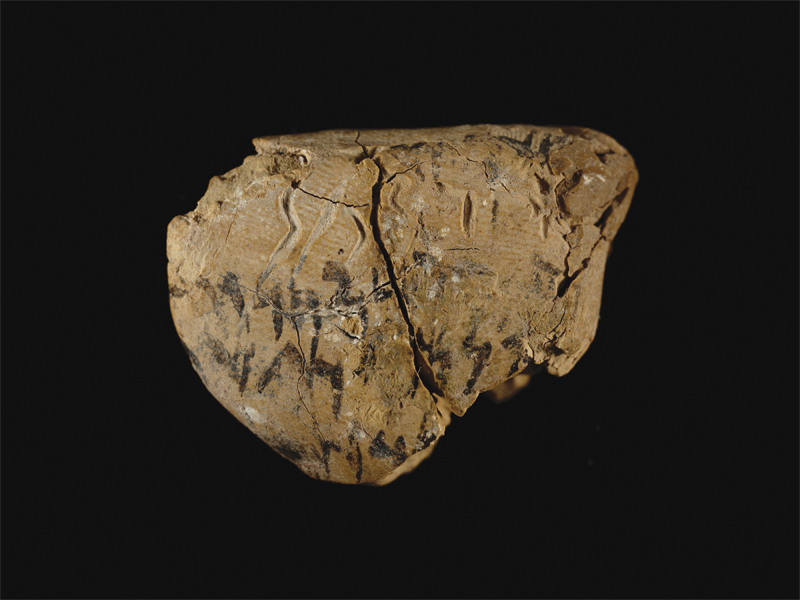

At first glance, the tablets are unlikely candidates for a 21st-century controversy. Dating from a 20-year period around 500 B.C. during the reign of Darius I, they provide a picture of the day-to-day functions of a highly sophisticated empire. Most of the tablets are written in Elamite, a language so obscure that only a handful people in the world are capable of understanding it.

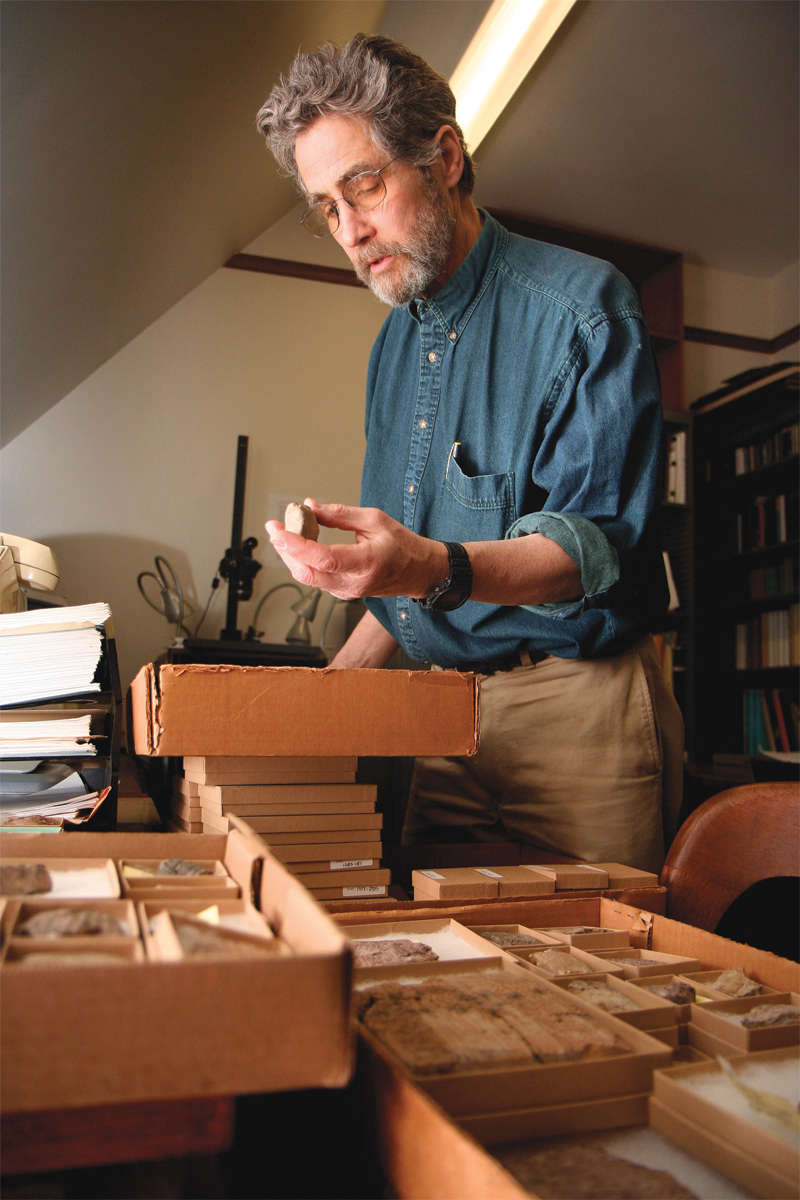

Matthew Stolper, a professor of Assyriology and Oriental Studies at the Oriental Institute, is one of those people and has worked at the helm of efforts to catalogue and analyze the archive.

Sitting in his office (which he occasionally refers to as the “fortress of solitude”), Stolper speaks candidly about the tablets. Taken on their own, he admits, they can make for dry reading.

“Who the hell cares if 30 guys ate so much barley each?” he says, punching the air to emphasize his points.

But Stolper does care, and he’s not the only one. There are currently 18 University of Chicago students and faculty members working on the project, as well as numerous other professors at universities from Amsterdam and Paris to San Antonio and Southern California.

Before the tablets were unearthed and analyzed, most of our information about the Persian Empire came from the Bible or Greek sources like Herodotus and Aeschylus—hardly unbiased accounts.

“[The tablets have] transformed the study of Persian and Greek societies,” Stolper says. “Anyone trying to portray this society without these does so at their peril.

“It’s not just some musty exotic thing. It’s now embedded in real society, the whole fabric of research, the creation of knowledge, history of language—it’s part of the whole enlightenment enterprise.”

The lawsuit that prompted the summons traced its beginnings to a Hamas-coordinated terrorist attack at a shopping mall in Jerusalem in 1997. Five people were killed and 200 wounded when terrorists set off suitcase bombs. Four years later, survivors of the attack and their family members—all U.S. citizens—brought suits against Hamas and Iran. The victims had sustained horrific injuries: severe burns, hearing loss, breathing problems—some were hospitalized for extended periods, one attempting suicide years later. Their case, Rubin v. The Islamic Republic of Iran, has wound through district courts around the United States and is not expected to end any time soon.

Though the attack was carried out by Hamas, the plaintiffs maintained that Iran had provided financial and logistical support to the group. Terrorism experts testified that Iran provided $20 to $50 million annually to Hamas in the 1990s and that government support for terrorism was an official Iranian policy. The court agreed, and the victims were awarded $71.5 million in compensatory damages and $300 million in punitive damages from Iran.

That was the easy part. There was little reason for Iran to show up in court to respond to the plaintiffs’ accusations, and it seems to have no intention of paying the damages awarded. The U.S. has recognized the county as a state sponsor of terror since 1984, and since then Iran has racked up billions of dollars in unpaid judgments.

There are also significant legal barriers to collecting damages from other countries. Historically, foreign countries have been exempt from legal action in the United States. The 1976 Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) states that the non-commercial property of foreign nations cannot be subject to seizure in legal judgments.

But terrorism, particularly state-sponsored terrorism, complicates things a bit. In 1996, Congress moved to expand the exceptions to FSIA in order to acknowledge the realities of state-sponsored terror: the law was amended allowing victims to sue countries for their terrorist acts. In 2002, the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act created a new way for individuals to collect on judgments against acts of terrorism, unblocking blocked assets.

When damages were awarded, the clients’ lawyer, Rhode Island divorce attorney David Strachman, who has won judgments for victims in other terrorism cases, fruitlessly searched for Iranian commercial assets in the U.S., such as bank accounts or real estate holdings that could be seized and sold. Museum artifacts, such as those at the Oriental Institute, as well as the Field Museum, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and Harvard University, all of which Strachman has also claimed for attachment, were the last chance.

In 2006, after the court found that the University did not have standing to assert Iran’s immunity from judgment under FSIA, Iran entered the fray, hiring the Washington D.C. law firm Berliner, Corcoran, and Rowe, which specializes in international law and intellectual property, to plead its case. The U.S. Departments of State and Justice have also jumped into the fray, filing three statements of interest that broadly support Iran’s and the University’s interpretations of the FSIA.

The case is now in the “discovery phase” in the Federal District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, during which the plaintiffs have requested information about all Persian artifacts in the Oriental Institute’s collection, as well as all of Iran’s assets in the U.S.

Adding another entanglement to an already complicated web, another group of plaintiffs have set their sights on the artifacts, demanding that any proceeds from the sale be used to satisfy a $2.6 billion judgment it obtained against Iran in 2007. They too have been waiting a long time: They are the survivors and over 800 family members of victims of the 1983 bombing of a Marine Corps barracks in Beirut. As lawyers for both groups of plaintiffs haggle with each other, Iran, and the University, the fate of the tablets remains uncertain.

To the scholars at the Oriental Institute, the idea that cultural items could be sold to satisfy a judgment, no matter how correct or well deserved, is inconceivable.

“It took a while for it to sink in that it was serious. I felt like it was impossible,” Stolper said of the lawsuit. “Then I realized they could really win. I had fantasies about chaining myself to the shelves when they come to take the tablets. I don’t know what I’ll do.”

In Stein’s view, the items are an inappropriate target for attachment in a lawsuit, on both legal and ideological grounds.

“Items of cultural heritage are a category that is very separate,” he said. “They are not items of commerce or trade. They have scientific value—they were legally excavated and loaned, never bought or sold. They’re not comparable to a ship, building, or bank account.”

“We have tremendous sympathy for the victims. The issue is not about the justice of their cause, [but] that it’s simply not appropriate to use these items to satisfy a damage claim. It’s just not right to commoditize cultural patrimony.”

But to Strachman, the victims’ need for compensation trumps concerns about the “appropriateness” of the procedure.

“What the University is effectively doing is trying to shield Iran,” he said. “What do they say to a U.S. veteran who was in the attack…who can’t get compensation?”

The stakes are high for both sides. Stolper worries that the tablets will lose their value as objects of research if they are separated and sold into different collections. Each tablet contains only a small amount of information—usually a short inscription or an engraved seal—useful only within the context of the rest of the collection.

“This is a unique archive—we know there used to be more [like this one], but we don’t have those,” Stolper said. “This is the unique survivor of something that was bigger. It’s like the last living speaker of a language, the last member of an endangered species. What are you going to do, cut up the body?”

Stolper also questioned whether the financial payoff could justify seizing the artifacts. Most are mere fragments, or in poor condition, and some bear no inscription at all. According to Stolper, those tablets would be of little value to prospective buyers.

“It’s mud that someone poked with a stick,” Stolper said. “The intrinsic value is nil. The value in academic terms is immense, but that’s contingent on having the entire archive.”

Strachman, however, says that the University’s concerns are exaggerated. In 2006, he petitioned the judge to appoint a receiver to arrange the sale of the collection. A receiver, he wrote, could work with museums and academic institutions interested in studying and displaying the tablets.

“The University says we want to hawk these on eBay. That’s just not true at all,” he said.

According to Strachman’s petition, a receiver, someone who will hold the artifacts and arrange their sale, would be best able to coordinate the collection’s most likely buyers and to structure a sale that is “appropriate to the nature of the property,” maximizing the sale price.

While the National Iranian American Council has issued a statement asking that people contact President Obama and the Justice Department to prevent sale of the tablets, Strachman cites Iranian expatriates, who claim the artifacts may be safer if they’re kept in the U.S. instead of returned to Iran. However the lawsuit comes out, it seems the question of what to do with the artifacts will remain significant.

But even if Strachman is able to assure that the artifacts are sold to an institution that will continue to facilitate research, the implications for cultural exchange will be significant.

Congress has attempted to expand the exceptions to the FSIA, in order to make it easier for victims such as those in the Rubin case to collect their judgments. Over the summer, it passed an amendment to the 2008 National Defense Authorization Act, which permits the seizure of hidden commercial assets belonging to state sponsors of terrorism and provides a federal cause of action against such nations to facilitate enforcement of judgments.

This more aggressive attitude toward victim compensation has already impacted cultural exchanges. To countries that frequently loan artifacts to American museums, the recent developments are discouraging.

Earlier this year, Syria withheld artifacts it had agreed to loan the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City for an upcoming exhibit. Though the museum requested that the State Department grant immunity for the loaned materials, there was concern that in light of the recent amendment, this immunity would be insufficient protection, according to a statement released earlier this month by the Archeological Institute of America.

“The whole structure of cooperation between countries—scientific cooperation between countries, cultural cooperation between countries—all falls apart if the U.S. gives these up [and] turns its back on tradition,” Stein said.

If museums are forced to relinquish and sell items loaned to them to satisfy judgments, Stein fears it could damage America’s already tarnished reputation for recklessness toward items of cultural value.

“We failed to protect Iraq’s treasures,” Stein said, alluding to the looting of museums and archeological sites following the U.S. invasion in 2003. “If we go the next step beyond negligence, to aggressively go out, seize and sell artifacts, it’s seen as trampling cultural heritage of these countries. What goes around comes around.”

The museum finds itself between the proverbial rock and hard place. Strachman points out that the sale of artifacts could be easily prevented if Iran would pay the proscribed damages to the plaintiffs.

“Instead of shilling for Iran, they should tell Iran to pay the judgment and move on,” Strachman advised the University.

But the Oriental Institute has to walk a fine line with many of the countries it deals with in order to continue displaying and studying the many artifacts it receives on loan each year. While the U.S. and Iran have not had formal diplomatic relations since 1980, the Oriental Institue has been able to engage in a kind of cultural diplomacy despite the volatile political climate. But pushing Iran to pay the judgment might keep the artifacts from being sold, but it could also damage the Institute’s relationship with the country.

“The Oriental Institute is able to work everywhere in the Middle East because everyone recognizes that our primary concern is scholarship and research,” he said. “We’re apolitical.”

While the implications for future exchanges and collections around the world are vast, “the “emergency,” as Stolper refers to it, has actually had some positive effects on East 58th Street. He and his team are working quickly to catalogue the tablets and preserve high-quality images online.

The weight of everything he had yet to do used to keep him up nights worrying, but Stolper now feels that if the case continues to move at a glacial pace and the project maintains adequate support, he and his team should be able to preserve most of the collection online, so scholars could continue to have access to it. Through collaborations with USC, UCLA, and the College de France, images of the archive will be accessible through at least four websites, allowing scholars to continue to study the tablets regardless of who owns them.

“[It] has galvanized me into doing work I’d been putting off for a long time, and putting it off has actually worked out,” he said, referring to the advances in imaging and sharing technology in the last two decades.

“It’s turned me from a dilatory, excuse-making, procrastinatory bum to a heroic defender of human culture,” said Stolper, who began working with the collection as a graduate student in the 1970s.

The urgency of the situation, meanwhile, has actually helped provide funding for the project. Grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Getty Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, among other organizations, have allowed the research to continue at an accelerated pace.

Stein notes that the University has also been unwavering in its commitment to the Oriental Institute’s position. “If it had to be anywhere, I’m grateful to be at a university where important principles are shared by all who have decision-making power,” he said.

Stein points out that it was ping-pong that cracked open the door to communication between the U.S. and China in the 1970s. He hopes that cultural exchanges can similarly maintain links between the U.S. and Middle Eastern countries.

But whenever this case is finally resolved, one senses that the professors at the Oriental Institute would like nothing better than to retreat from the real world a bit, immersing themselves in the past. As Stein puts it, “We exist in the real world; there are times when it’s more difficult and times when it’s easier.”