As a low-income student, I know that there are people in my life whom I will seemingly never be able to repay. And within that pool of individuals—family members, friends, and those who saw within me what I failed to see in myself—is the roundtable of admissions officers who decided my life’s trajectory in a grand total of 30, maybe 45 minutes.

The phrasing is almost slightly too dramatic, even for me, but the sentiment—and more importantly, the reality behind this statement—is wholly true. My family is small, a band of Polish immigrants condemned to perpetually repeating one another, whether in conversation or in life: My grandmother raised her children largely independently, ostracized by suburban Michigan after deciding not to live in one of Detroit’s Polish-speaking enclaves. By the time I was in middle school, it was my single mother and her children against the world.

As a child, I was shy, sensitive, and intimately aware of my family’s finances. I was always urged—half jokingly, half with a grave seriousness, and often in Polglish—to get out as fast as I could.

I’ve never seen my mother cry the way she did when I was accepted into UChicago.

I don’t believe in anyone being “owed” anything beyond human decency. And no matter how qualified I was, or how good my “fit” was, or even how deserving I may have retrospectively been, getting into UChicago was not the sigh of relief for me as it had been for my family. It felt like I was now due to stand trial.

Today, having almost completed my first year at UChicago, I feel it necessary to lend my voice as a source of advice to future low-income students and families considering UChicago, and to articulate how my undergraduate experience, short and unfinished though it may be, has been molded by my socioeconomic status.

Along with my acceptance letter in December of 2020 came the conclusion that, if nothing I do would ever “match” what UChicago did for my family, I would be spending my entire undergraduate career proving that the institution made the right decision in taking me.

I felt like an investment—specifically an investment I had to make good on. I was content with moving the invisible goal post on behalf of those whom I sincerely believed were out there, who took a chance on me, and were now watching. I was prepared, and even eager to push myself, so long as doing so prevented anyone from seeing any cracks in the veneer.

Besides, my complete lack of a success metric is what had motivated me to push through a high school where I felt under-stimulated, misunderstood, and honestly, completely apathetic. In a self-righteous, seventeen-year-old way, it kept me off the path of complacency.

I could keep that same thing up for four more years, I thought.

Halfway through fall quarter, I barely recognized myself.

For the first time in my life, I was celebrated by others for my socioeconomic status and the obstacles I had supposedly “overcome.”

I was also completely and utterly mortified by just how behind I felt I was.

After my first Advanced Biology (AB) lab, I walked back to my dorm with tears in my eyes. The tears weren’t necessarily a product of the lab itself (after all, it was largely an introductory session), and there is an admittedly masochistic quality to the AB sequence in general—most students are brought to tears by siRNA pathways or chromatin organization at least once.

I cried because I didn’t know how to use a pipette. My high school hadn’t had any.

After my lab partner realized I had absolutely no clue what I was doing, she took the pipette out of my hands and completed the four-hour-long lab alone in silence. In retrospect, I cried afterwards not out of embarrassment, but the fact that I, someone who had always relished in, sought out, and thrived in spaces where I could prove others wrong, was paralyzed by how correct I believed her assessment of me was: a girl who was completely in over her head.

I hated calling home during this period. The same stubbornness I had inherited from my family clashed with their refusal to let their faith in me falter; it was virtually impossible to communicate that I wasn’t simply being hard on myself, that I was actually struggling.

(After listening to my frenetic, sleep-deprived ramblings mere hours before an Honors Chemistry midterm, my mom jokingly suggested I switch to law—“like her!” —and I bawled in a Max P study lounge.)

Even over the phone, I could hear the sheer belief that my family had (and continues to have) in me, how proud they were of their kochanie.

It crushed me then, and it occasionally crushes me now.

I initially hesitated to write this column because I continue to feel inadequately prepared to provide future low-income students advice on how to navigate UChicago’s academic and social landscapes. My perspective is also a privileged one, in that it fails to encompass the unique challenges incurred by members of UChicago’s first generation, low income, immigrant (FGLI) community who also walk this campus as people of color and/or first-generation students. But that very feeling of “incompleteness”—the dissonance between my desire to give nuanced words of wisdom and the simple fact that I’m only two quarters through the journey myself—is at the heart of my best piece of advice.

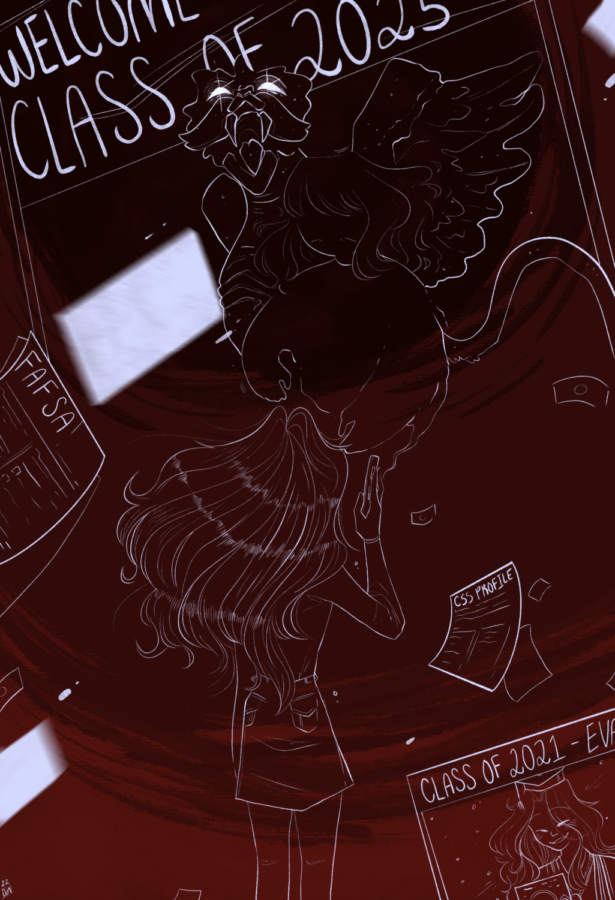

To the prospective students who are all too familiar with late nights spent pouring over FAFSA and CSS documents, with consoling your loved ones who mourn all they wish they could have provided, with the agonizing wait: I urge you all to remember during your time here that I am, and each of you are, perpetually unfinished.

I am everything left unfinished by my grandparents, who spent their entire young adulthoods with their eyes to the sky as airport employees in Poland and later took flight themselves, arriving in Michigan with 10 dollars. I am everything left unfinished by my mother when she became a single parent and dedicated her life to instilling within my two brothers and me a genuine love for education.

I am the sum of everything left unfinished by those who believed in me despite my circumstances, so much so that they put their own lives on pause to support me as I worked to become who I am today.

From the moment you step foot on this campus, you must carry this gratitude with you like a torch. Your gratitude, and your constant knowledge of where and who you come from, is what will ultimately serve you more than anything else, even in the face of self-doubt, imposter syndrome, and others’ attempts to assess the validity of your place here. It is this gratitude that will also enable and empower you to advocate for yourself with grace, be it to other students or University administration itself. In doing so, conversations pertaining to your socioeconomic status will no longer leave you either continuously “on the defensive” or blind to the genuine investments others have in you.

You must also note that you are, fundamentally, a work in progress, working towards your own individual ambitions, hopes, and goals. You are not just the culmination of your loved ones’ wildest dreams—you are the culmination of your own.

Finally, many of you are your family’s “firsts.” The swell of pride this may give you when celebrating your admission may dissolve into fear, nerves, and confusion when confronted with the first few weeks of fall quarter, because your “firsthood” comes with your support network starting with you.

I am the first in my family, the youngest daughter in a family of low-income immigrants, to have to reconcile with being “the first.” That is where the anxiety lies, the being overwhelmed, but also the sheer and exciting vastness of where you may go.

And, while calling myself a “success story” feels all too much like a line out of a Humane Society ad, I would encourage those that share my same inability to know when enough is enough to search for little wins. I eventually learned how to use a pipette—so well, in fact, that I’ll be one of two TAs for a summer version of the same course I thought would devour me whole. I still email and occasionally grab lunch with the UChicago admissions representative who, knowing my economic status, enthusiastically told my 16-year-old self during my campus tour that Hyde Park was where I was meant to be.

At the end of the day, there are people who care about you here. You will meet them in the Center for College Student Success, at the FGLI student socials, and spaces where your socioeconomic status is never brought up or mentioned at all. Arriving to UChicago’s campus on its own is an act of great defiance in the face of others’ misconceptions, perceptions, and expectations of you—the onus is on you, over the next four years, to cultivate that same resistance through telling your story and allowing it to define you how you want it to.

Eva McCord is a first-year in the College.