Yasen Peyankov Is Spectacular in Steppenwolf’s Deep and Disturbing “Describe the Night”

Deputy Arts Editor Zachary Leiter reviews “Describe the Night,” a strong, character-driven retelling of the life and death of Russian Jewish writer Isaac Babel.

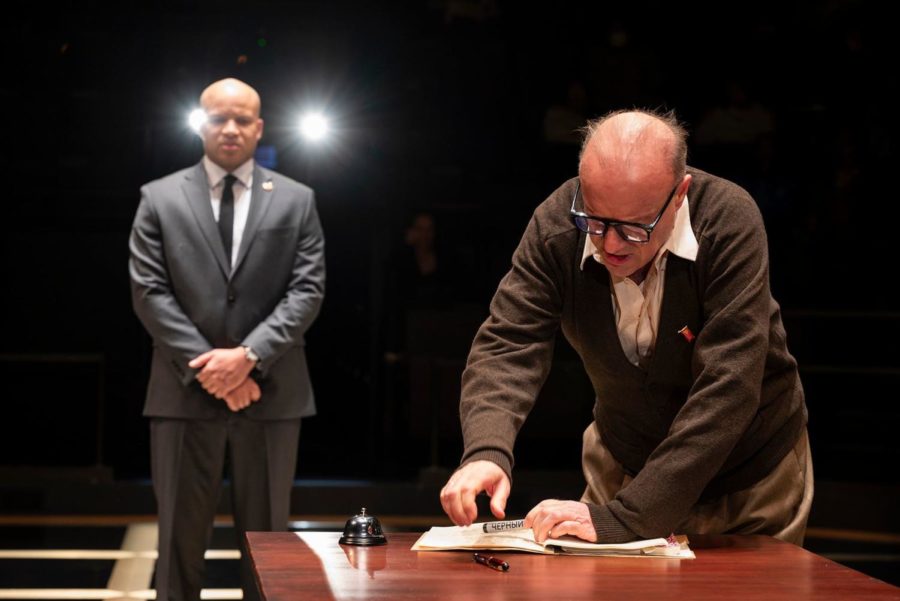

Glenn Davis (left) watches as Yasen Peyankov (right) re-writes Soviet history with a black marker.

April 10, 2023

This spring at Steppenwolf, Rajiv Joseph’s Describe the Night is an elegant, witty, and perceptive dramatic reimagining of the life and legacy of Russian Jewish writer Isaac Babel. The famed author of Red Cavalry and Odessa Stories, Babel was arrested by the the Soviet Interior Ministry (NKVD) in 1939 and executed on fabricated charges of treason and espionage the following year. Joseph’s drama is equal parts thriller and history, half accurate, half reinterpreted, entirely stirring.

Describe the Night follows seven Russians as they interact with Babel’s diary between the rise of the Soviet Union and a sort of pseudo-present day. The writer and his diary are introduced during the Polish-Soviet War along with then-Army Captain Nikolai Yezhov (another historical figure), who would go on to become the tyrannical head of the NKVD. Nikolai, like Babel, was executed for treason in 1940. The play imagines a reality in which the two were close friends and Nikolai was not actually murdered, but simply reported to have been killed. Describe the Night so consistently twists and amends not only the historical truth but also the play’s own established plot that the effect is a constant state of fear and uncertainty. Joseph’s greatest success is surely that he has managed to write a play that effectively recreates Stalin’s three-decade atmosphere of distrust and danger in under three hours.

It is also a play of incredible savagery, disguised in caricature and comedy. The brutal Nikolai, played with grace and wonderful wit by Yasen Peyankov, broods at the center of the horror. There is truly no gap between Peyankov and Nikolai; such is the skill in accent work, posture, and expression. Nikolai develops before the audience’s eyes from a young, rigid officer to a cruel, calculating killer to a hushed, sadistic bureaucrat who secretly oversees the Soviet Union’s archives after his faked death. In many ways, Peyankov brings disturbing sentimentality to a monstrous figure. In another way, Nikolai’s evolution is a quiet and clever metaphor for the evolution of the Soviet Union. When he is eventually relieved of his duties in the 1990s, Nikolai is replaced in office with the new wave of Russian authoritarianism: the Putin-esque NKVD agent Vova.

Also splendid in a strong ensemble cast were Caroline Neff as Mariya, a journalist reporting on the Smolensk Air Disaster of 2010, and James Vincent Meredith as Babel. As her character is interrogated by Vova, Neff provides a soundless strength that bristles against her enemy’s ferocity. She is one of the handful of women in the play who present compelling alternative ways to find personal stability in a nation undergoing constant turmoil. Meredith’s strength is a soft one, too, carried through his powerful words—and, therefore, the play implies, carried into the present. The power of Babel’s words almost saves the writer, even as the peculiar and subversive nature of Babel’s words are what put him in peril.

Isaac Babel has come to be regarded as one of the great Russian prose writers, and Describe the Night‘s dialogue evokes Babel’s voice marvelously in its emotional understatement and lyricism. Especially delightful is a long play-within-a-play about ducks, acted out by Babel, Nikolai, and Nikolai’s wife Yevgenia. Describe the Night is not afraid to dwell when it finds a subject worth dwelling on—such is a mark of the greatest plays. This duck scene, the play’s opening, Babel’s death, and many more scenes stretch on and on, often sustained by penetrating discussions of ‘truth’ and Peyankov’s dry humor.

Indeed, Describe the Night is not merely pretty; it is deeply insightful about the dangers of rewriting history (and the ease of doing so), something the play generally knows itself to be doing. Watching the play, the audience has as difficult a time deciphering the truth, as do the characters. This effect is created not through unclear plot, nor through intentional vagueness, but rather through Nikolai’s constant rewriting of history. With a simple statement by the Soviet government, Nikolai was killed. With a black marker, the undead man changes official records—not only erasing history, but changing individuals’ lives with a single stroke of a pen. “Lie” is perhaps the most spoken word in the play, beginning when Nikolai asks Babel again and again, during a dark night in Poland in 1920, to lie to him, an ability Nikolai finds to be fascinating and the mark of a writer.

The mark of a writer compared to a killer, it turns out, is not whether he lies, nor even how artful he is in his lies, but rather in what he does with his lies. Terrifyingly, Describe the Night suggests that the distinguishing factor between whether a lie becomes evil or acceptable is whether or not one is in a position of relative power.

Describe the Night is not a perfect play—that would be a hard task, given the long runtime and such sweeping drama. In particular, Jack Cain as the modern youth Feliks and Charence Higgins as Vova’s lover and Feliks’ mother, Urzula, though not poor in performance, fall short compared to the rest of the cast’s depth of character. Additionally, the ending of Describe the Night curiously abandons the play’s general skepticism and methodical treatment of questions of veracity, opting instead for moral condemnation of Vova, delivered by the ghosts of Feliks and Mariya.

But, all in all, this is a play of remarkable insight and genuine beauty. There’s an elevator built into the ornate in-the-round stage, a smart array of fur coats, and a soup filled with leeches. Horrific brutality and sensitive subjects—such as Nikolai’s sexuality—are addressed with precision and poetry alike. This is the power of the written word, from Babel to Nikolai to Describe the Night. That Describe the Night wields the pen in much the same way as Babel and Nikolai—albeit for wildly different ends—forces the audience to confront the play’s most worrying meta-questioning of where truth lies.

Rajiv Joseph’s Describe the Night was at Steppenwolf Theatre through April 9th.