In the fall of 2022, I walked through the doors of the Ratner Athletics Center for the first time. Before entering the cramped breeding ground of gym bro–philosophy bro hybrids who work out with Kant in one hand and a dumbbell in the other (seriously, I have seen this on multiple occasions), I found myself in front of a shrine dedicated to collegiate athletic triumph.

I paced through the circular exhibit, examining the glass cases full of black-and-white images and awards. The first thing I noticed was that a significant portion of the encased items were dedicated to football: National Hall of Fame awards, pennants, jerseys, and commemorative footballs with astonishing scores embossed upon them. I had seen this sort of thing on visits to other schools like UT Austin or Northwestern, but it felt out of place here.

Especially confusing to me was the ball with the score: “Chicago–15, Michigan–6.” The fact that we had played against, let alone beat, the University of Michigan, a school with one of the most notoriously dominant football programs in America, startled me.

The centerpiece of the installation was a bronze figurine of a man in a Discobolus-esque stance, with one arm holding a football, the other outstretched defensively: the Heisman Trophy.

The Heisman, the most highly sought-after individual award in collegiate football, was sitting in the lobby of the recreational gym at perhaps the most notoriously dorky school in the country. From that point on I was hooked, and instead of working out, I turned back to my dorm room and scoured the internet searching for answers.

Sure, maybe it started as an excuse to skip a workout, but my curiosity quickly spiraled down a rabbit hole that seemingly had no end. I spent the following months in the Special Collections Research Center, digging through boxes of old newspapers, correspondences, and student dissertations. I quickly came to learn that UChicago’s relationship with football is convoluted and deeply intertwined with its campus culture, student life, and the University’s strict philosophy as an institution that prides itself on rigorous academic pursuit.

Harper’s University

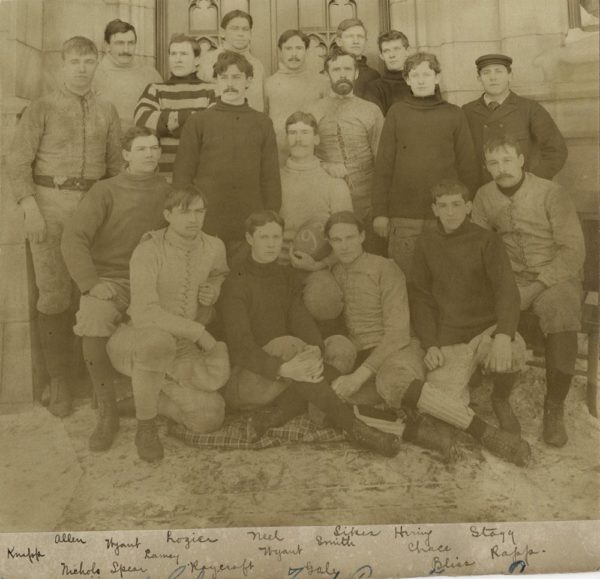

UChicago’s relationship with football sprung out of the philosophy of the University’s first president, William Rainey Harper. In 1891, determined to build a team that would dominate the gridiron, Harper hired Amos Alonzo Stagg to be the athletics director and head football coach for the Maroons. Hiring a coach in a tenured position was unprecedented, but it was the obvious move for Harper, who saw football as a key aspect of his uniquely American university. Harper aimed to build an institution that embodied the academic excellence of Oxford while remaining American in culture. Excelling at football, a sport synonymous with the American way of life, was the key to his vision.

Harper made his high expectations clear in his offer letter to Stagg for the coaching position, writing that he wanted a team that would “knock out” the competition. Stagg was a known wizard of the game and had received higher-paying offers from established programs like Yale. But Stagg wanted to build his own legacy from scratch, and that new school on the Midway was the perfect blank canvas.

Stagg pushed his team hard for the first three seasons, touring the country to play the most formidable opponents in the surrounding states. In 1896, after establishing some legitimacy, Chicago joined Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Purdue, and Northwestern to form the Western Intercollegiate Conference, more colloquially known as the “Big Ten.”

Football spilled over onto the quad and enveloped campus culture. Similar to the dominant schools of today, tickets to games were in high demand, and students even had to compete with the general public for a seat at Stagg Field. Business was booming, and the boys on the field were dominating a sport that was on the rise nationally. Bringing the stadium to full capacity each home game, the rowdy fans would cheer along to the beat of Big Bertha, the world’s biggest bass drum.

In one instance, after an 1896 victory over Michigan, more than 200 students skipped classes and flooded the halls. When the cavalcade passed Harper’s office, he joined in, marching alongside the students whose school spirit had become a significant source of profit for the University.

As far as recruitment went, Stagg was in charge, and athletic ability came first and far above proficiency in the classroom. In certain cases, players were yanked out of high school for training before they finished their senior classes.

This kind of special treatment for the men of the football team carried on throughout their time on campus. They enjoyed access to specialized training facilities, country club retreats, and a far lighter workload than the average UChicagoan.

A 1902 Chicago Tribune article describes the players as “gridiron warriors [who] have not yet descended to the level of ordinary students.” They possessed “distinctions shown to them to which the common ‘grinder’ cannot lay claim.” (Yes, even in 1902, UChicago students studied hard enough to earn the title of “grinder.”)

After all, it was necessary to keep these students on the field and to persuade a new recruitment class each year that would outplay opponents. The most effective way to do that was to advertise being on the football team as a privileged position among the student body.

Knowledge Above All

By 1920, the Maroons were two-time national champs, and Stagg had attained legendary status. But some on campus began to question whether the Maroons’ dominance was contradictory to one of the core values of the University: putting knowledge first.

Following America’s post-war economic boom, schools like Michigan, Harvard, and Notre Dame spent millions on grand new stadiums to ensure their place among the elite, while UChicago stood idly by. In 1923, Ernest Burton became president of the University. Burton placed less of an emphasis on athletics than his predecessors, Harper and Judson. Burton denied Stagg’s request to fund an entire new stadium, instead opting only to install two new grandstands. This decision marked the beginning of the end of Stagg’s reign on campus.

Burton and his successor, Max Mason, continued, with the support of trustees and other administrators, to place checks on Stagg’s power. The old coach was no longer able to recruit in the aggressive manner he once did, and player stipends were strictly off limits. Unable to compete with other universities in the recruitment process, the Maroons saw their losses begin to outnumber the wins, and the program collapsed.

Hutchins, the Executioner

Enter Robert Maynard Hutchins, a young scholar who intended to establish UChicago as an elite institution of higher education when he acceded to the office of the president in 1931. Hutchins inherited a dying football team: Coming off an 85–0 loss to their formal rivals, the Michigan Wolverines, the Maroons were decrepit.

A Yale graduate and higher-education idealist, Hutchins saw football as an obstacle in his path to making UChicago a sacred space dedicated strictly to the pursuit of intellectual enlightenment.

Hutchins took Judson’s recruitment restrictions even further, essentially banning recruitment altogether, and stripped Stagg of whatever power the old man still had. As a result, attendance, victories, and interest amongst the student body and faculty fell steeply.

In a 1931 “Open Letter to the ‘Old Man’”, The Daily Maroon called for the retirement of the almost 70-year-old head football coach. Two years later, Amos Alonzo Stagg coached his 42nd and final season at Chicago.

In the years following, under coach Clark Shaughnessy, the team saw little to no success on the field. Outside of the spectacular performance of Heisman award winner Jay Berwanger in 1935, the W-L column was dreary. It had become clear that the University had made the decision to put athletics aside, and the football team was as good as gone.

The Abolition

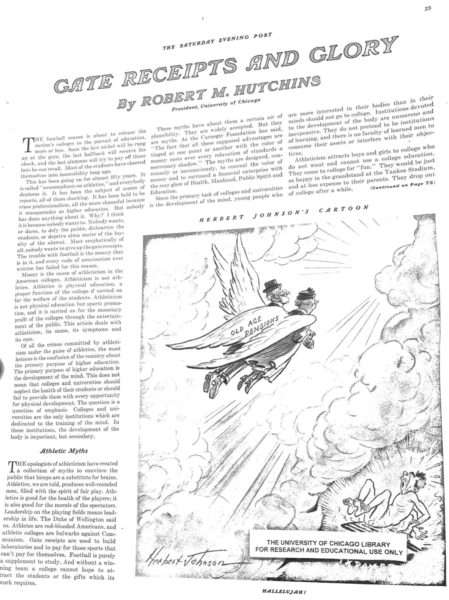

In December of 1938, Hutchins wrote an article—really, more of a rant—in The Saturday Evening Post, titled “Gate Receipts and Glory.” The piece is a striking, unfiltered account of Hutchins’s true opinion on the place of football, or lack thereof, in higher-education institutions. Voicing his disgust with the commercialization of intercollegiate athletics, Hutchins tore apart the “athletic myths” that promoted football as the ultimate indicator of a successful university. Hutchins saw intercollegiate football as a “financial enterprise with the rosy glow of Health, Manhood, Public Spirit and Education.”

Such unethical practices did not belong at the prestigious safe haven of morality Hutchins aimed for UChicago to become. To him, UChicago was “a different kind of college,” one where students attracted by athleticism—students who “come to college for fun”—did not belong.

The same year he wrote his searing piece, Hutchins sent a letter to the Board of Trustees recommending the indefinite discontinuation of the “handicap to education” that was the football program. In its hopeless state, the team had two choices: to dismantle itself entirely or to return to aggressive recruitment and subsidization of high school players. To Hutchins, the latter was immoral and impossible to do “without departing from our principles and losing our self-respect.”

Shortly after receiving the letter from Hutchins, the board of trustees voted unanimously to abolish varsity football at the University of Chicago.

The decision was more of a relief than a tragedy for most students. In an op-ed titled “Delayed Obituary,” writers at The Daily Maroon expressed the relief that the abolition provided the student body. Football was long dead, the Maroons had no hope of competing with fellow Big Ten–ers, and its presence only threatened the preservation of the “intellectual ideals” of the University.

Equally important as academic rigor was the maintenance of a certain level of prestige at the University. Some advocated that the Maroons, rather than dissolve completely, just play smaller schools. This option was rejected because, according to Robin Lester’s 1974 Ph.D. dissertation on football history, Hutchins was “fearful that playing small schools would diminish Chicago’s status as a premier university.”

And so it was decided: The serious athlete and the serious student were separate entities, and the University of Chicago was only a place for the latter.

1963: The Return

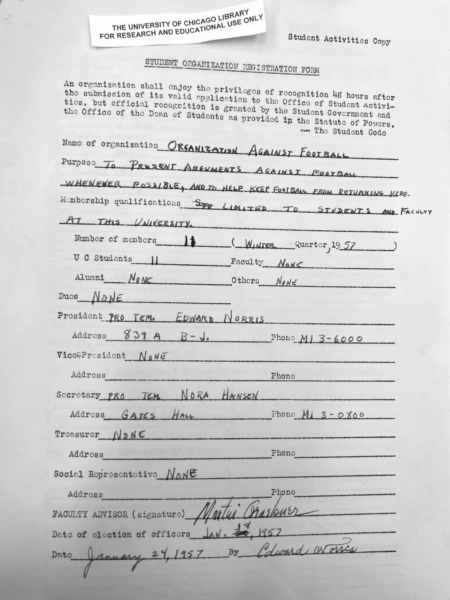

The ol’ pigskin remained tucked away for 24 years following the abolition, and the bleachers of Stagg Field were converted into a quantum research lab where physicist Enrico Fermi created the world’s first sustained nuclear chain reaction. Football didn’t return as a topic of discussion among UChicagoans until 1956, when the Committee on Student Interests brought forth a petition to bring football back to campus, citing that “students do not have much fun at college.” The Board of Trustees struck the petition down unanimously.

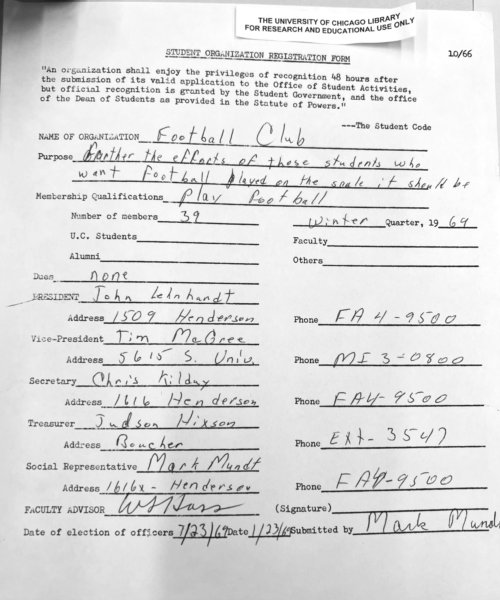

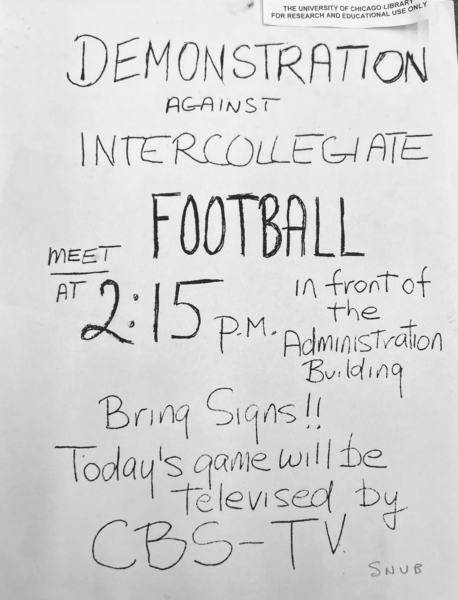

The majority of the student body vehemently rejected the notion that football be brought back, and following the failed petition, some students formed an “Organization Against Football” RSO, serving to “keep football from returning” in the case of a future debate. But, in the years following, those who wanted to play football felt as if their rights were being restricted by the ghost of former president Hutchins. Seven years after the 1956 petition, enough aspiring players gathered together to form their own “Football Club” RSO and the sport returned to campus.

With the support of some alumni and faculty, ideas began to float around regarding the specifics of football’s return. In a 1959 letter to former Pepperdine University president Norvel Young, Dean of the College John Netherton wrote, “We do now have tackle football classes in the Autumn quarter as part of our Physical Education program, and a very high proportion of our undergraduate men participate in intramural touch-ball.”

In the same letter, Netherton outlined the strict requirements necessary if football were to reemerge, stating, “There would be no buying of athletes. We would not lower our admissions standards to obtain football players, nor would we institute ‘snap’ courses to allow athletes to get by academically.”

Even the Undergraduate Student Government warmed up to the idea of a football team on campus, claiming that it would be a “violation of civil rights” for students to be denied the ability to participate in the sport.

“Students felt that they were here, in part, because it was a different kind of place,” former University president Hanna Holborn Gray told me. A place, they thought, that prioritized academics over football.

The return in 1963 was not the product of a spontaneous change in spirit amongst the students and faculty but simply “a football club that mustered enough players,” Gray said.

This was no attempt to resurrect the glory days, and if it was, the students who were against the return made sure their voice was heard at the first scrimmage. In quite a hilarious exhibition, student members of an offshoot organization of the Organization Against Football, held a sit-in on the 50-yard line at Stagg Field.

“So it was one of the more hilarious but appropriate episodes in our history that one of the first sit-ins to take place at the University would be on the 50-yard line to guard against something like the restoration of football,” Gray recalled.

The demonstration was short-lived, and the season went on without any further interruption. The Maroons began on a path to redemption.

Division III: A New Era

Throughout the ’60s, UChicago football gradually progressed from a class to a club to a scrimmage team, and finally, in 1969, the program became a founding member of the NCAA Division III league.

In his short time as University president between 1975 and 1978, John Wilson wanted to do something that many at UChicago and beyond had not considered a possibility: make football fun.

“He had a positive view of sports; he wanted to improve and widen the scope of student life,” Gray said of her predecessor.

Wilson, a former swimmer, supported the expansion of DIII athletics during his time as president, hoping to legitimize the barely funded football scrimmage squad.

“The idea was to have a league in which institutions that are more or less similar in terms of their athletic resources and their philosophy about sports might enjoy playing each other and maybe have pizzas together after a game,” Gray said about the founding of the division.

DIII gave the Maroons a smidgen of credibility, and with that came some extra financial support. Players weren’t getting post-game ice baths and personal massages, but at least they had locker rooms where they could change.

As an homage to the former coach, the DIII football championship game was dubbed the Amos Alonzo Stagg Bowl, though to this day, the Maroons have yet to compete in it.

Football for the Thinking Man

In 1957, Stagg Field was demolished, and construction began on the Regenstein Library. The massive brutalist structure took 13 years to finish and stands today as a monument to academic rigor. With the shadow of the old stadium having been erased, football at UChicago entered a new age.

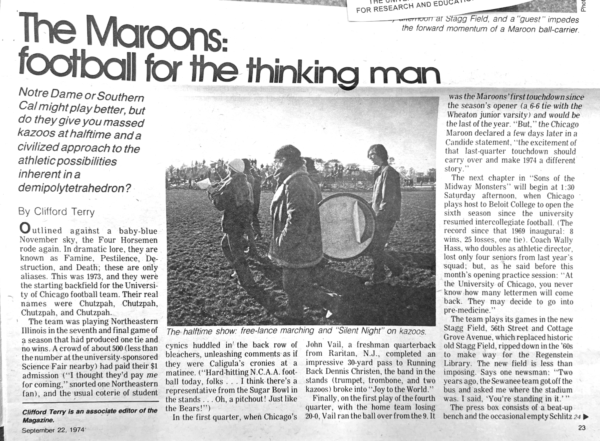

“The Maroons: Football for the Thinking Man” was written in bold above the Sports section of the Chicago Tribune on September 22, 1974.

“The team plays a brand of football in which punts travel 20 yards, and 90 percent of the passes look like intentional grounding,” wrote the article’s author, Clifford Terry.

The sprawling piece focused not just on the team’s poor performance but on the absurd fanaticism of the student body. Bandana-sporting students would gather in the stands of the new Stagg Field—a meager 1,000-person-capacity field—and cheer on their team with the screeching of Big Ed, the world’s biggest kazoo.

“The students in the stands seem to be divided in half,” the quarterback at the time told the Tribune. “Some like to watch football, the rest like to smoke and drink wine.”

To cheer on the troupe, the article says, students shouted chants such as “Themistocles. Thucydides, Peloponnesian War. X square, y square, H2SO4,” or my personal non-rhyming favorite, “One-two-three-four, Five-six-seven-eight, Nine… Ten!”

Gray described the atmosphere as “good cheer and a little bit of Saturday Night Live.”

Just as they pioneered the creation of “big-time” football, the Maroons were helping to take the seriousness and commercialization out of the sport.

“Half the boys weigh less than their IQ, and most can’t make it to practice because they have a lab, or an essay to write,” the head coach at the time, Wally Hass, told the Chicago Tribune.

The team’s inability to compete was part of the attraction. Students at UChicago basked in their athletic failure. For some, the comic incompetence of the team was a testament to their academic excellence; others just found joy in the humiliation.

The players knew they weren’t good, but winning wasn’t necessarily the objective; they were just happy to be on the field at all.

“It’s fun; this is what college football was meant to be. We try hard to win, but if we don’t, nobody loses his scholarship,” defensive lineman Mike Krause (M.B.A. ’72) told The New York Times.

From the 1970s forward, Division III grew, and so did the football program at UChicago. But the game-time atmosphere today is not what it was in the heyday of DIII football.

Football as it Stands

Having finished his first season with the Maroons, head coach Todd Gilcrist was eager to speak to me about the program. Gilcrist is no stranger to universities with academic reputations that far outshine their athletic programs, having previously held coaching positions at the College of the Holy Cross and at Columbia. To him, though, UChicago’s history with the sport makes it a unique place.

Before we began our conversation, Gilcrist reached into his bag and fished out a copy of Jeff Rasley’s Monsters of the Midway, a book that focuses on the strange counterculture atmosphere of 1970s UChicago football.

“It’s one of those things that I think when you hear about Alonzo Stagg, when you hear about the first Heisman Trophy, then you hear about the academics of this university and how that’s been able to kind of pair with athletics,” Gilcrist said. “Athletics are a part of this university.”

At the same time, though, Gilcrist still subscribes to the Hutchins spirit, putting academics first for his players.

“If [the players] need to go to office hours or have to come to practice a little bit later because of class, we allow for those things because we know how important that part of this experience is,” he told me.

With mostly empty stands (outside of our annual homecoming game), the game-time atmosphere at Stagg Field today does not match the roaring energy of the ’20s, or the eccentricity of the ’70s; but, for the players, Gilcrist believes the program offers an opportunity “just to get to play the game that they love, go out there on Saturdays and play in front of however many fans.”

Fourth-year William Goodman, starting kicker for the Maroons, echoed that sentiment, telling me, “There are no scholarships. We aren’t getting paid. You’re there because you want to be.”

Goodman preached the personal benefits of being on the team—“It really bolsters you as a student and a professional”—and he credited that to UChicago’s position in Division III.

“If you gave me the chance to play in Division I, I wouldn’t take it,” Goodman said. “I prefer Division III because I care more about investing time into my career and fostering relationships with my friends than I do about being the best football player.”

Both Goodman and Gilcrist made it clear that for the player, the football team still offers the same sort of camaraderie it has since our university first joined Division III. But for the nonathlete, the football team really doesn’t intersect with life on campus at all.

“I think that everyone could do a better job about showing up to games and representing the school. There also needs to be more of an incentive from the athletic department,” Goodman told me.

I will admit, I have never really attended a single football game on campus aside from a brief visit to the homecoming game last year. But that’s only because these games don’t offer much to students, and there is no connection with the team. The bleachers were mostly full of the parents of students or players, and I definitely didn’t notice any clever chanting. It would be easy to write it off as a symptom of our team’s size, but when I look back at the 1970s, I see an even smaller team with more student engagement. Evidently, there’s something else afoot.

When asked about the possibility of reuniting the student and student athlete at future games, Goodman emphasized the notion that football players don’t lack any of the dorkiness and academic obsession of nonathletes: “The team is a bunch of nerds who like to play football,” he said.

Goodman points out something crucial missed by most students and student athletes on campus today: We are all still nerds in some capacity. What the Maroons of the 1970s did was embrace that fact and use it as motivation to bring students to the stands. Who’s to say that can’t be done again?

What Now?

Each time I enter the Ratner lobby, I can’t help but stop before the Heisman Trophy to pay my respects. Now, as I pass the plaques and pictures displayed around the lobby, I feel the phantom thumping of Big Bertha, and I envision the stern-faced Hutchins watching Stagg Field crumble to the ground. Mostly, I am reminded of how much the exhibit is missing: The abolition is barely mentioned, and there’s not a single kazoo in sight.

I definitely didn’t come here anticipating thrilling football games. In fact, I stood with Hutchins in his belief that athletic spirit had no place at this university. But here I am, arguing the opposite. If I knew nothing of the student sit-in or sarcastic chants, I wouldn’t think twice about our football team, and I surely wouldn’t possess such an interest in the future of the program. But something about our uniquely UChicago way of finding a place for athletics struck a chord with me. Perhaps it is in embracing our past that we students can establish a connectivity that transcends both athletics and academia and bring football back into our future, this time for good.

Penny / Sep 30, 2025 at 9:15 am

Great article! Thanks!

I was a U of C cheerleader back in the 80’s and we still did the “Themistocles, Thucydides, the Peloponnesian War; X-squared, Y-Squared, H2SO4” cheer. Also: “Interception, Contraceprion, Stop that ball”. We made a pyramid while chanting “CH-Chicago” which we did 4 times as we moved into formation ending with “What is CH4?” and the crowd roared out “Methane”!!!

Another cheer that has been especially helpful to me in remembering Pi was this one: “E to the X, DY, DX; E to the X, DX. Cosine, Secant, Tangent, Sine, 3.14159. Who for? What for? Who the heck are we cheering for? Go Maroons!” It was fun. We all

laughed at ourselves. Thanks for bringing these memories to mind! —Penny Lindgren Nicholas ‘83 (my former roommate and fellow cheerleader Laurel Erwin Lyle ‘84 brought your article to my attention).

Robin Lester / Sep 10, 2024 at 10:53 am

I’m sorry that the writer did not read Big Time Football at the University of Chicago (University of Illinois Press, 1995). It was

my Ph.D. dissertation at Chicago in the History Department (Profs Arthur Mann & Dan Boorstin) and the Best Book Award winner of the North American Society of Sport History. The paperback edition came out in 1999. It was, and is, an assigned reading in many universities’ cultural history courses.

The Stagg Papers were assigned to me by Special Collections Director Robert Rosenthal; I had to edit the whole collection so that I could cite much of the material for my dissertation.