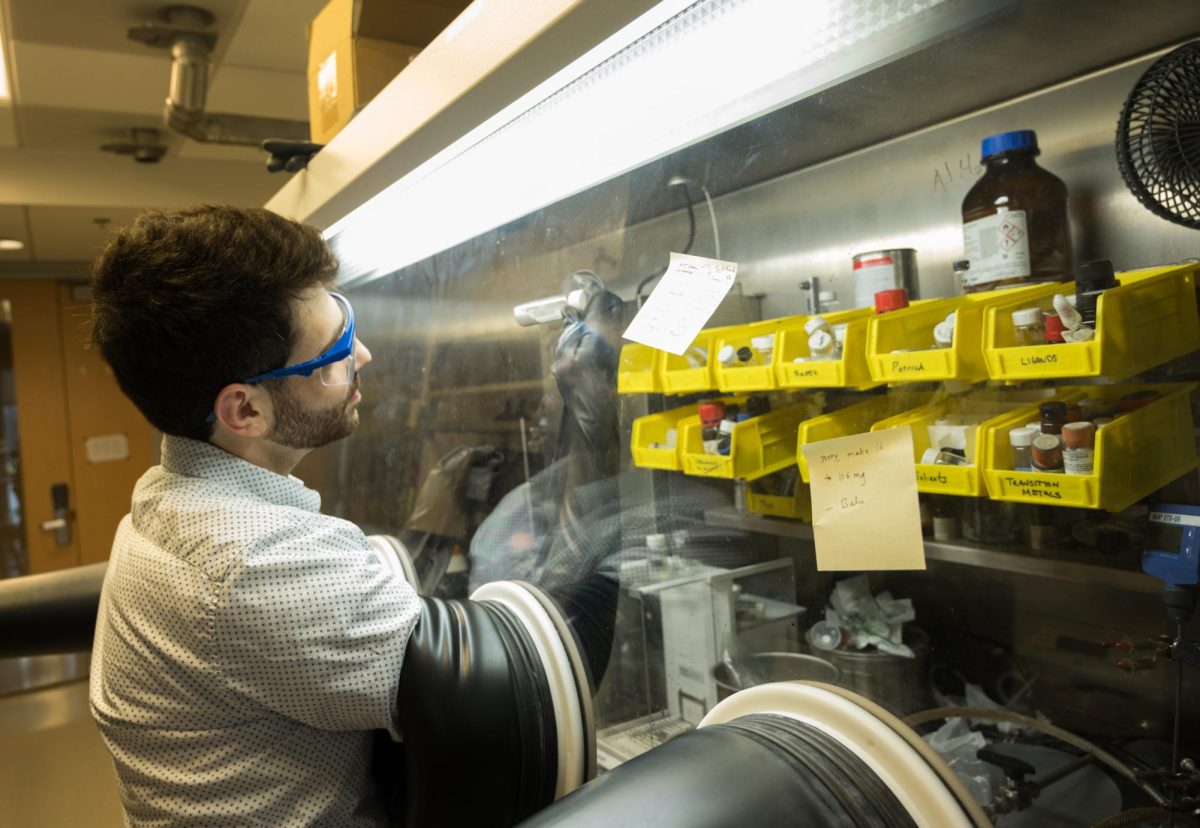

When synthesizing new drugs for pharmaceutical purposes, medicinal chemists will experience success or failure depending on differences as small as a single atom. The Levin Lab, an organic chemistry lab at UChicago led by associate professor Mark Levin, has found two strategies to replace a carbon atom with a nitrogen atom. The breakthroughs, published in Science and Nature this fall, could make developing new drugs easier.

The Maroon spoke with Levin about the recent discoveries made by his group. Acknowledging the difficulty of developing new drugs, Levin called synthetic chemistry a “multidimensional optimization problem.”

“[The drug] has to be efficacious, non-toxic, [and] absorbed in the gut in order to be in oral therapy,” he said.

Most drugs in development have some, but not all, of these requirements. Fortunately, the swapping of a carbon atom with a nitrogen atom radically increases the chance of meeting these parameters by allowing chemists to fine-tune many properties of chemical compounds, including “hydrogen-bonding, polarity, metabolic stability, target specificity and solubility.”

However, making modifications at the core of a molecular skeleton compared to its periphery is rather difficult. It’s like changing layers during the winter: It’s easy to swap a jacket but hard to put on a new shirt without taking the entire outfit apart. Put on the wrong shirt, and the process becomes a chore.This interest in skeletal editing—swapping out individual atoms without disassembling molecules—is not exclusive to the Levin Lab. Levin is among a group of chemists to pioneer the term “skeletal editing,” which has been used in over 100 scientific papers in the past two years.

With the promise of developing drugs without synthesizing compounds from scratch, Levin suggests two ways to replace the carbon atom: first, attaching a compound containing three nitrogens to a carbon ring, and second, replacing a carbon with nitrogen after breaking a double bond between two carbons using ozone.

The first paper published in Science on September 28 was led by postdoctoral researcher Tyler Pearson, who works in Levin’s lab. The paper reports that carbon is replaced wherever a three-nitrogen compound, known as an azide, is placed. While there are many ways to attach the azide, their findings suggest C-H functionalization, in which the bond between carbon and hydrogen is broken, serves as a segway for nitrogen replacement. If chemists can dictate which carbon is exiting, they can understand how replacing different carbons affects a drug’s molecular properties.

The second paper published in Nature on November 1 was led by postdoc Jisoo Woo. It focuses on existing carbons in a ring of atoms containing two or more elements. Using ozone to open the ring, the cleaved structure can then accept nitrogen and close again.

Similar to Pearson’s approach, Woo’s findings were built off decades of preexisting knowledge about transformations. The choice to use ozonolysis, or using ozone for cleaving, was based on “hundreds of years or more of transformations we wanted to try. Ozonolysis was the best out of all the different reactions that we could apply,” Levin said.

The two papers align with the group’s culture with what Levin calls a “modality agnostic lab.” “We are more interested in ‘here’s the class of problem we want to solve’ and we’ll use whatever technique we believe to be appropriate,” Levin said.

The lab actively supports ideas that resonate with students. The projects carried out are largely inspired with the creative direction of its lab members.

“Creativity is the most valuable currency in science. I never found systemization to be particularly conducive to creativity,” Levin said.

In contextualizing his lab’s work, Levin understands that it will take more time to turn these conceptual advances into proven industry tools. More work needs to be done in academia overall to make these advances more user-friendly so that they can be used on a commercial scale.

Still, Levin is excited about the lab’s findings and the future directions of his group’s research. “This is really the first time that we developed a reaction that really deserves to be turned into the best possible version of itself.”

Nahshon Moturi / Dec 28, 2023 at 3:44 pm

Thanks for sharing.

Do you have medical laboratory results for moringa oleifera plant leaves, roots, bark, seeds, flowers and oil?

Esther / Dec 27, 2023 at 5:13 am

Wow this is awesome