As an international student from France, I had never heard of land acknowledgements—until I started the college admissions process in the United States. Hearing each university’s admissions representatives begin events and tours, both online and in person, with these statements soon became familiar. But when I first virtually toured UChicago in July 2022, I was surprised when the information session skipped it. The absence of this mark of awareness toward the history of the United States was troubling, but I quickly dismissed it to focus on the slideshow.

One year later, as a disoriented international student running to numerous O-Week events such as the Opening Convocation or the Aims of Education address, I again started noticing that the University did not feel the need to remind us of the tribes who originally lived on this land.

The land acknowledgements of peer institutions like Stanford, Harvard, and Yale—as well as other Illinois universities like the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Northwestern—are easily found online and feature in official documents and statements from their administrations.

At UChicago, certain departments and offices employ land acknowledgements. The Office of Civic Engagement, for instance, co-wrote a land acknowledgement with the American Indian Center of Chicago in 2021, and the Chicago Center for Teaching and Learning issued an online statement about the “historical context” to their diversity and inclusion policies.

The University of Chicago at large, however, remains officially devoid of land acknowledgements. The Laboratory School’s student newspaper reported in October 2023 that the University barred the high school’s science department from adopting an official land acknowledgement because it violated the 1967 Kalven Report, a university document that suggests an official “independence from political fashions, passions, and pressures.”

“It is disheartening that the smallest step, the littlest gesture of acknowledgment isn’t even taken here,” said Elijah Bullie, a third-year in the College who descends from the Omaha tribe and co-founded the Indigenous Students Association (ISA) at UChicago.

But Indigenous student opinion is mixed. Second-year Lukas Borja, who is also part of the ISA and of Indigenous heritage, believes that land acknowledgments often feel hollow. At universities, they often act as a placeholder for concrete changes to the curriculum—a token gesture, rather than a meaningful one. “Land acknowledgments are one step and how they operate at most universities now, in my opinion, is that they come in the absence of any concrete changes to curriculum or procedure,” Borja said.

Todd Henderson, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School who studies Indigenous law (but is not of Indigenous descent), is of a similar mind. “I don’t think land acknowledgments do anything other than assuage people’s guilt,” he said. “If the University of Chicago was to erect a statue of Native people who made contributions […] or have a Native American history requirement, yes, I would love it.”

But concrete changes are, of course, difficult, given the University’s refusal to adopt what it sees as political speech.

This official obstinacy, Borja argued, is “even more absurd for the city of Chicago, in the state of Illinois.”

“A lot of people think of Chicago and the Midwest, and even the U.S. overall, as very separate from an Indigenous past,” Bullie added. But in reality, the two pasts are tightly intertwined.

The name “Chicago,” for instance, comes from a French rendering of the Miami-Illinois word shikaakwa, meaning “wild onion” or “wild leek,” plants that were widespread in the area we now know as the city and University of Chicago. This swampy region by the lake was originally a complex and diverse fur trading center for more than thirty tribes. Among them, the Ojibwe, Odawa, and the Potawatomi—together known as the Council of the Three Fires— were the most influential in the Great Lakes region. This economic, political, and military alliance lasted for centuries and played a key role in trade and wars between tribes and European powers.

However, starting in the 1760s, the Great Lakes native tribes experienced a decline in their populations as warfare and disease spread. This phenomenon was amplified by migration—both forced, after land concession treaties following the War of 1812 between roughly ten tribes including those forming the Council of the Three Fires and the young, growing United States, and voluntary as some tribes anticipated American expansion and others remained nomadic.

By the 1840 census—the first to include Chicago— no Native Americans were recorded as living in the area (although Indigenous people underreporting their own numbers is partially to blame for this dearth). As a consequence of their demographic decline and lack of appearance in official records, it is very unlikely that Native students were admitted when the University was founded, although no ethnic records were kept.

Today, the number of Native students at UChicago is only 0.1 percent—roughly one or two students entering per class—a number which is around average for the University’s peer institutions. By contrast, Chicago is believed to be home to the third-largest urban Native American population in the United States with over 34,500 individuals (1.3 percent of the city’s total population) according to the 2020 Decennial Census.

One explanation for this is the federal government’s 1952 Urban Relocation Program which encouraged Native Americans to leave reservations for seven cities including Chicago. It was formalized through the 1956 Indian Relocation Act. The government’s goal was to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American society. As better life conditions were promised to them by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), over 100,000 Native Americans left their reservations for cities between the 1950s and 1970s. But the reality which awaited them in the cities was bleak as they faced unemployment, poverty, culture shock, and racism with little help from the BIA. Once the Bureau had directed Native Americans towards housing, often in underprivileged neighborhoods, and a job, often offering small revenue, it left them on their own.

The University’s relationship to this Indigenous history and presence is equally complicated and largely grounded in academics and theory. The most substantial option to study Native history and current issues is the new Race, Diaspora, and Indigeneity (RDI) program. Replacing the Critical Race and Ethnic Studies major, which was last offered to the Class of 2025, the RDI major requires students to take “Foundations of Indigeneity,” a course about the evolution of Indigenous identity and the political and environmental concerns facing Native people. For students interested in the field but reluctant to commit to the major, a few Civilization courses such as “America in World Civilizations” and “Human Rights in World Civilizations” also examine the topic.

The AICC, a moment of change in Indigenous matters organized by UChicago

Despite these options, most graduates of the College will never study Indigenous culture. Currently, only 20 undergraduate students major in Critical Race and Ethnic Studies and only 13 major in RDI, according to the University’s Winter Quarter 2024 Census Report. (For reference, 1498 study Economics, the most popular major.)

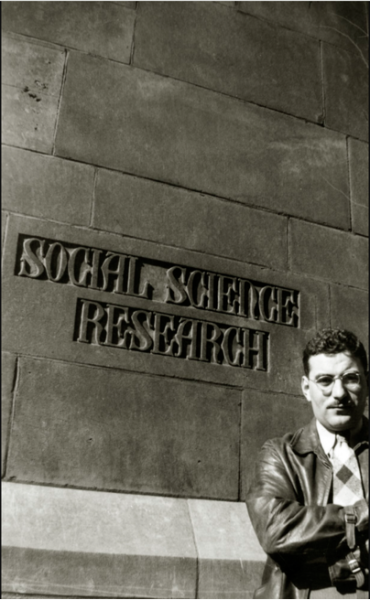

But the University has long supported research and events in the field. In 1961, the American Indian Chicago Conference (AICC) was held on campus and partially funded by UChicago. Organized by Dr. Sol Tax, professor of anthropology at the University, the AICC put into practice Tax’s theory of “action anthropology,” the study of cultural and social challenges that promotes self-determination for the communities involved. The conference was one of the first events to promote Native self-determination, encouraging Native Americans from various tribes to confront their issues and formulate their own solutions.

Over 500 Native Americans from 90 tribes attended the conference, where they discussed issues such as preserving Native cultures while adopting some elements of American culture and designing programs to improve their collective future. The conference resulted in “The Declaration of Indian Purpose,” a document advocating for the protection of Indigenous rights and identities against forced acculturation, which delegates from the AICC presented to President Kennedy at the White House in 1962. Reflecting on the conference’s legacy, Professor Henderson, the Law School professor, said that “it was incredibly important in the Indian Civil Rights Movement and in getting it started.”

After the conference, the University continued to play a consequential role as the publisher of Indian Voices, a periodical born of the AICC newsletters and coordinated by Dr. Tax. Any Native American could send a letter to the editor, Robert K. Thomas, a Cherokee who was trained as an anthropologist at UChicago, and it would be published. Every issue of Indian Voices was accompanied by copies of treaties and policies concerning Indigenous people to provide them with extensive background on the political relationship between the government and Native people and to expand their English vocabulary.

An opportunity for Law Students to support the Hopi tribe

In recent years, the University has expanded areas of research in Native American studies through its support of an innovative Law School program. Everything started when Henderson, a Law School professor, and Justin Richland, a UChicago anthropologist and associate justice on the Hopi Appellate Court, met at a Little League baseball game. Both were interested in Native American Law and reinvigorated the Law School’s interest in the field by teaching a Native American Law seminar.

In 2016, they went further by starting a practical course entitled “The Hopi Law Practicum” which enabled Law students to act as a “legal aid clinic,” as Henderson described it, for the Hopi Court. There, students assisted judges and worked on land disputes, contracts, and disciplinary action cases pending in the Hopi Appellate Court.

Henderson said that the students loved the Hopi Law Practicum, describing the chance to witness living conditions as “eye-opening.” A cornerstone of the program was also realizing the distinctions and similarities between Native American reservations and the rest of the United States. “Going there […] it is unmistakable that you are in America, but you also feel that you’re in a completely different place,” Henderson explained.

The Hopi Law Practicum was spearheaded by Richland, who used his relationship with the Hopi tribe to enable students to enter a “very closed society,” as Henderson put it and witness the intricacies of their “different-but-the-same” legal system. Once he left UChicago for the University of California, Irvine, in 2018, the program ended, although Henderson still aims to revive the program, perhaps with another tribe.

Indigenous students create their space at the University beyond the classroom

On campus, the University also supports events and programs involving Indigenous people (even if they are not necessarily widely advertised outside of the involved departments). UChicago is one of 21 member institutions of the Newberry Consortium in American Indian and Indigenous Studies, a program for graduate students across fields to conduct research, dive into Indigenous archives, and present their work at a conference. For undergraduates, the RDI department also organizes events about Indigenous history and current issues.

For instance, Raymond Orr, a professor at the University of Miami of Potawatomi descent, gave a talk entitled “Indigenous Polities: Flexibility Across Time and Settler State” on October 26, 2023, on campus. There, to a crowd of largely RDI students and faculty, he began with an acknowledgement of the tribes who used to live in the Chicago area. Orr explained how federal legislation limits the ability of Native Americans to break apart from their tribe, start a new one, or join another tribe to which they are not related.

Outside of academics, Native American and Indigenous presence and heritage are now embodied by a newly created RSO: the ISA. Bullie recalls that when he arrived at UChicago, he and Danielle Lopez, a third-year of Lenca and Tagalog Filipino descent, were shocked at the lack of an Indigenous student group: “Oh my gosh, everyone has a group! Where is ours?” he said. The former Indigenous group, the UChicago Native American and Indigenous Association, was no longer active. The two friends decided that “if they’re not gonna make a space for us, then we’ll just make one ourselves,” Bullie said. The ISA, co-founded by Bullie and Lopez, finally came to be during Winter Quarter 2023.

Reflecting on the tiny proportion of Native students at UChicago, Bullie recalls touring the Law School and discovering that only one Native American student was enrolled. “It’s just things like that that remind you just how alone you are,” he said pensively. But for Bullie, the ISA has been particularly important because “it gives a space for people like me to not feel so alone.”

Consequently, as a co-founder of the ISA, it has been crucial for him to build a sense of community between Native students and raise awareness that despite their small percentage, they are present and active on campus. Their last event, held on Indigenous People’s Day—October 14, the same date as Columbus Day—was entitled “Pie a Colonizer.” On the Quad that Saturday afternoon, ISA members could throw a cream pie in the face of a man dressed up as a 17th-century colonizer. Bullie said that this event helped the ISA gain visibility. Indigenous students who had not previously heard about it were excited to discover that such an RSO existed at UChicago.

However, he was surprised at the amount of reproach that the group faced on the Quad. As he considers the University to be a “very accepting campus where people, for the most part, are culturally aware,” he was shocked to witness some passersby yell at the group from across the Quad and give them dirty looks. “If people know history, I don’t think there’s a way to say that you’re a fan of Christopher Columbus,” Bullie said. “But that was what they were yelling at us on the Quad: ‘Christopher Columbus is a hero.’”

Concerning these conflicting perspectives on history, Borja argues that universities have a duty to advocate for truth and historical awareness. “So much of our active struggle is demanding historical recognition and the right for our historical realities to be viewed as such,” he explained, noting how Native students across the country often encounter false narratives about their past and culture in class. Even at UChicago, he said, there is still work to be done about the historical representation of Native people in certain American history courses.

As expectations grow for universities to raise awareness of Native American history, Bullie wanted to remind students that the Native American community is present on campus—and not simply an object of study: “We’re real, we’re happening, now is the time.”

Anonymous NDN / Apr 8, 2024 at 2:16 am

I graduated from here recently, but it’s honestly the worst university to attend as a Native. You’re always going to be the only one in every classroom. Although UChicago has amazing anthropologists and RDI now, but it was unnecessarily traumatizing and intellectually unstimulating. Again, do not come here if you’re Native.

Salikoko S. Mufwene / Feb 16, 2024 at 3:25 pm

Great article! For those interested in more courses about Native Americans, I have taught the following course, cross-listed with RDI this winter (and also in spring 2022), in which we also discuss the marginalization of Native Americans and, in connection with land dispossession, the fact that they basically become foreigners in their ancestral land: Race, Ethnicity, Language, and Citizenship in the United States.

Alan / Feb 12, 2024 at 6:24 pm

great article ! I learned a lot on a very original topic . Looking forward to more articles thanks

Joe Biden / Feb 9, 2024 at 3:40 am

A really stupid article from a woke fruitcake.

Veritas / Apr 9, 2024 at 2:59 pm

Lack of knowledge.

Marianne / Feb 8, 2024 at 9:51 pm

Such an insightful article! Very inspiring to see the impact actions led by students and faculty have had despite the school’s lack of land acknowledgement.

Sid / Feb 16, 2024 at 3:51 pm

Not only does the school have no land acknowledgment, departments are actively prohibited by the Office of the Provost from having one on their departmental websites.

Dorene Wiese / Jul 10, 2024 at 2:01 am

Wonderful article! As an Ojibwe graduate student, I was lucky enough to go to UC with a cohort of Native students. I would love to meet the new students and have them visit our community .The only thing missing from the article is that in 2010 & 2011, we had two more conferences at UC to talk about National NativeUrban issues. The School of Social Work hosted us. There are videos on your website.Message me on FB, Dorene Wiese P.S. I have 2,000 mostly Native books I am giving away.