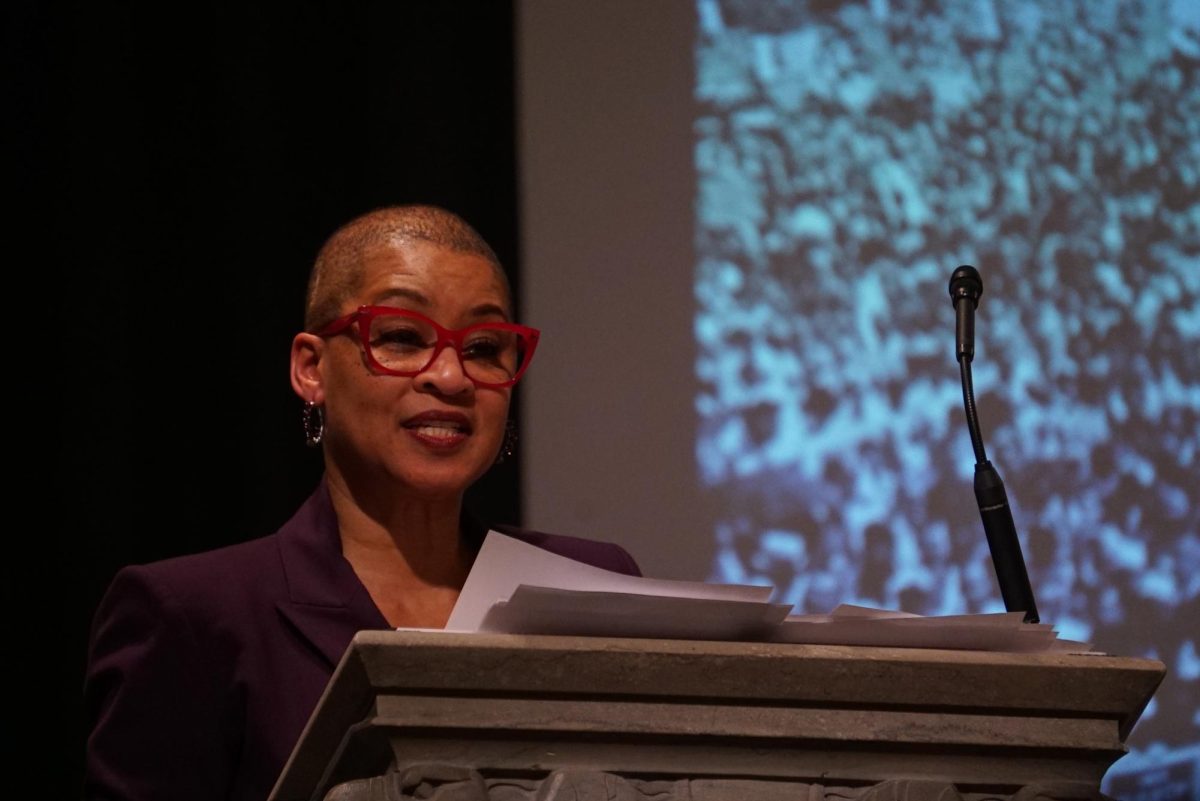

On October 10, former Prime Minister of the Palestinian Authority Salam Fayyad and professor Tom Ginsburg, founding faculty director of the Chicago Forum on Free Inquiry and Expression, discussed the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict at International House. The talk was the first installment in a series titled “What Might Peace Look Like?” hosted by the Chicago Forum on Free Inquiry and Expression.

Ginsburg opened the discussion by reflecting on the Oslo Accords, a set of agreements signed in 1993 between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The accords stipulated that Israel would accept the PLO as a representative of Palestinians in exchange for the PLO renouncing terrorism and officially recognizing Israel’s right to exist. They also established a Palestinian National Authority to govern the West Bank and Gaza Strip for five years before permanent solutions could be discussed. Fayyad, who was serving as an International Monetary Fund (IMF) representative during the signing, recalled its importance and how it had initially been a source of excitement in the international community.

“I was, at the time, a national civil servant with the IMF… in Washington, DC, when the actual declaration of precedence of the world was signed on 13th of September, 1993, and I remember it was so momentous,” Fayyad said. “The IMF, which, as many of you know, is very conservative—institutional, strong traditions—interrupted the meeting of the executive board at the time to actually watch the event. It clearly was a big deal at the time it happened.”

In spite of the optimism and grandiosity that had surrounded the Oslo Accords, Fayyad noted a lack of clear framework for Palestinian statehood, pointing out that, although the Accords initiated peace negotiations, they failed to explicitly reference the establishment of a Palestinian state. “From the very beginning, I was struck by something that actually came back to haunt everybody,” Fayyad said. “Maybe, at the time, people were banking on… the strength of goodwill and strong interest [for a Palestinian state]… [from] the international committee to deliver on… the state for Palestinian people. Nowhere… will you find, in the documentation, that is Oslo… any reference to Palestinian statehood.”

As the discussion continued, Ginsburg expanded upon this notion of Palestinian statehood, focusing mainly on the challenges surrounding it. He explained that, while “you could even argue that there is a [Palestinian] state in the legal sense,” the bureaucratic capacity to function effectively is still key to achieving statehood. Ginsburg said that, although Palestine has been recognized as an official state by 138 of the 193 United Nations members, he believes that this recognition has not yet translated into tangible statehood.

Likewise, Fayyad explained his frustration at the gap between international recognition and the actual reality of daily life for Palestinians.

“If you’re in Gaza today, and somebody says, ‘150 countries recognize Palestine,’ that’s political fiction,” Fayyad said. “It feels good that we have these countries recognizing… the state of Palestine, but in the absence of a credible path forward to… be really stable, it’s political fiction.”

Ginsburg and Fayyad also discussed the titular question of the talk—what might peace look like—offering both historical insights and potential first steps.

“Conflicts like this [the Israeli-Palestinian conflict] do end,” Ginsburg said. “And what is required, from my point of view, is that you have moderates on both sides who are willing to do a deal with each other and that can control the people who want violence…. And in a way, what happened in Oslo is that the hard-minders spoiled it very quickly.”

“Peace, just peace… is about the absence of tension,” Fayyad said. “[If we want to resolve this,] let’s begin by getting rid of the tension…. Prioritize bringing about ceasefire in Gaza.”

The event was also marked by two interruptions by protesting audience members. During the middle of the initial conversations on stage, one protester interrupted by accusing Fayyad of having “Palestinian blood on your hands,” criticizing his leadership during the Second Intifada, and asserting that his failure to recognize that “the only way to freedom is the resistance” resulted in countless deaths. During his tenure as prime minister, Fayyad focused mainly on state-building and economic growth rather than on the brewing tensions with Israel, which made him unpopular among some Palestinian factions.

“You should be ashamed of coming here…. You were in charge of killing so many people,” the protester shouted.

After a few minutes of the protester’s speaking, Ginsburg stepped in, trying to emphasize the importance of free speech and reminding the protester of the scheduled Q&A in which they might better voice their concerns.

“I’d like to just say something about free speech, which is, of course, [that] we welcome questions,” Ginsburg said. “If you were to get up in the question time and ask such a question, that would be acceptable. The problem [with] such disruptions, [is that] they are patronizing to everyone else in this room.”

Shortly after, the protester was escorted out of the room by security. Approximately 20 minutes later, two other audience members hoisted a banner and distributed pamphlets explaining “Fayyadism,” Fayyad’s philosophy to never “confront them [Israel] for your full rights,” and stating that he “cut off salaries to thousands of Gazan public service employees… [because] they worked against ‘Palestinian legitimacy,’” among other things.

During the official Q&A, which began just a few minutes after the interruptions, Fayyad addressed the protesters’ criticisms, reflecting on his own leadership.

Fayyad acknowledged the effects of his broader political strategy during his tenure as prime minister and also explained his reasoning. “I bear full responsibility, and I do not think [well] about… it. I don’t feel about it,” Fayyad said. “But this is how the other things were, and I thought we had a shot at actually changing things…. And that did not happen… for [a] long list of reasons.”

Ultimately, Fayyad and Ginsburg agreed that the path to peace is still quite difficult and one in which the underlying issues of justice and statehood must be addressed.

“Our right to a state has to be recognized, and that has to be the starting point of the conversation,” Fayyad said.

Matthew G. Andersson, '96, Booth MBA / Oct 14, 2024 at 8:04 pm

It is fascinating that a major R1 research university feels that it needs a discrete “forum” to host multi-source information. If it otherwise sought to interrogate the nature of Middle East controversy, Mr. Ginsburg would invite the chairman of the Board of Trustees of the University of Chicago, who cofounded the single largest defense investment corporation in the US, which financially backs the Israel and Ukraine oil, gas, water and mineral control programs (the operations are conjoint). Or he would initially host John Mearsheimer from Political Science, which would be intellectually inconvenient for the academy. Those interrogations are not likely, at least in any classic “Chicago School” format; the Forum is not configured for fact-finding, or ideological falsification. Moreover, like the C19 project, these are not per se free expression issues, but rather special interest financial, economic and ideological ones. Mr. Ginsburg serves to guard those interests institutionally, and obscure the inherent realpolitik character of political conflict–as the Pearson Center does. As philosopher Martin Buber stated, human nature seeks to be deceived. That is the Forum’s utility, and the cultural and professional routine of the modern law and public policy school.