Editor’s note, December 27, 12:00 p.m.: João Pedro do Prado Sanches is a member of the Smart Scholars Program, hosted by the Feitler Center for Academic Inquiry within the Smart Museum. Starting in January 2025, he helped select works for Smart to the Core: Wise to Power, write exhibition labels, and produce its online catalog.

Pre-registration has just opened. In the spirit of adventurous inquiry, you choose one of the most traditional options to fulfill your social sciences requirement: Power, Identity, Resistance (PIR).

With texts ranging from the classic Thomas Hobbes to the contemporary Christine Korsgaard, students in PIR explore themes related to the formation of the state, economy, and political recognition. At first, all these canonical texts do is make you stay up late. After a few classes, you realize that the authors are all, to some degree, trying to understand why and how people form and manage political communities. But why should this matter now, when we live far from Hobbes’s “state of nature”? Smart to the Core: Wise to Power, a new exhibition at the Smart Museum of Art, takes up this very theme, not only asking the same questions as the Core sequence but also giving viewers new ways to answer them.

Most authors read in PIR are either Europeans or Americans, most are men, and most are white. But the exhibition Wise to Power shows that outside of the West, individuals were also wrestling with similar questions. In the early 19th century, the English artist Thomas Rowlandson etched House of Commons, depicting the lower chamber of the British Parliament. More than giving political visibility for the “commons”—townspeople distinct from the nobility in the House of Lords—the print shows a social organization defined by state and class. Around the same period, Japanese artist Ryuko painted Four Classes of Society, a scroll showing a samurai, farmer, artisan, and merchant organized in descending order. By visually placing each figure below the other, Ryuko also displays the hierarchy embedded in Edo-period Japan’s social organization.

Both Rowlandson and Ryuko captured their realities by depicting different forms of social organization. Together, these works reveal how all social orders are constructed, rather than natural. Across the West and beyond, authors and artists have wrestled with how individuals arrange society. This concern is as important today as it was then: if societies have changed from their time to ours, they can change again from today into the future. The remaining question is: how? The answer to this question depends—in PIR it depends on the author, and in Wise to Power it depends on the artist. In the screen print Land Where My Father Died, for example, artist Barbara Jones-Hogu advocates for social change as a form of collective historical reparation fueled by popular revolt. Artist Bob Thompson, on the other hand, proposes in Herding of the Cows a way to imagine the future, taking into consideration narratives of the past that once were silenced.

Although they think about similar themes, artists and authors work in different mediums. While authors express their vision by building a sequence of ideas using written words that form sentences, one after the other, artists are limited to the visual depiction of a single moment in time. In a brilliant 1766 essay, the German dramatist and art critic Gotthold Lessing wrote that, because artists must choose only a moment in time to focus their depiction, they “must therefore choose the one which is most suggestive and from which the preceding and succeeding actions are most easily comprehensible.”

When reading a text in PIR, one might treat the material as one’s entire philosophical world because, given the nature of the written medium, an author can fully walk their reader through their ideas. But Wise to Power gives students the possibility to “look” at those ideas. To break down and interpret the composition of a given work in this exhibition, one has to both understand what the visual work is doing and what it does in relation to the texts and concepts of the sequence. The artworks both reinforce and challenge theories from different authors and, at the same time, allow students to find meaning and contradiction in ways that words alone often cannot.

In a given year, PIR students read around 13 authors over three quarters, though this can vary depending on the instructor. Classes in UChicago’s social sciences core requirement are sequential: this allows students to build one idea on top of the other and think about one author in terms of another. But at the same time, because it is not possible to read 13 authors simultaneously, one might end up with an overly linear understanding of the authors’ ideas.

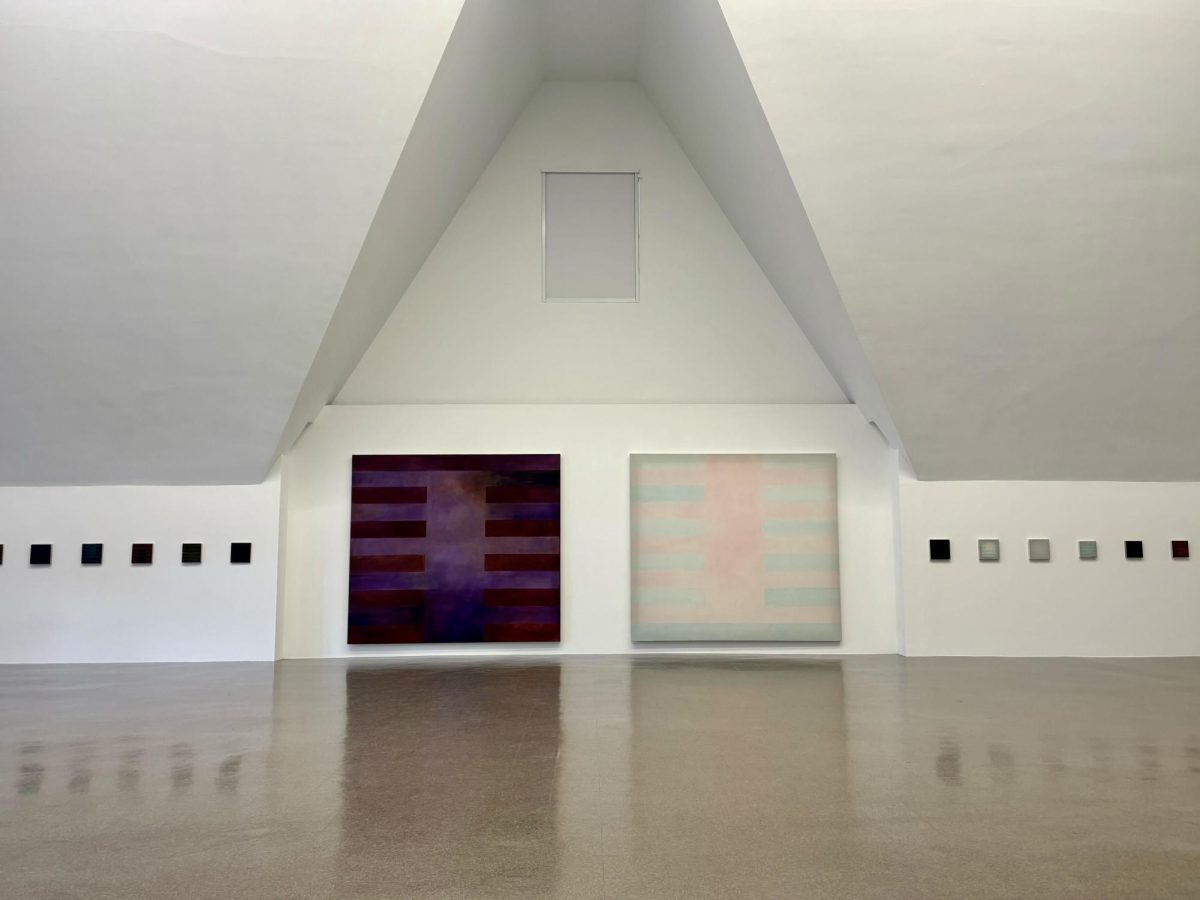

An exhibition like Wise to Power changes this dynamic: all works are physically present in the same space, at the same time. This simultaneity allows students to engage bodily with multiple works concurrently and non-linearly—they might walk around a sculpture while considering a nearby painting or porcelain piece. Exhibitions invite one to move from one work to another without a rigid order, providing an opportunity for students to form connections between works and themes present in PIR that they otherwise might not. This spatial experience reminds us that these ideas are all interconnected through the entire sequence.

Smart to the Core: Wise to Power is not simply an attempt to give a visual language to the themes covered in PIR. Rather, it functions as a pedagogical tool to enhance students’ experience with the sequence by showing how visual production can both illuminate and complicate the same debates that philosophers articulated in writing. At the same time, the exhibition also denaturalizes our present reality by revealing that the structures shaping society are constructed rather than a given. In doing so, it extends the classroom experience, reminding students that the questions they encounter in texts are not limited to theory but are lived and contested by real people—including themselves. These questions, like the works on display and the texts in PIR, remain open to challenge and new reinterpretation through art and history.

Smart to the Core: Wise to Power Part I is on view at the Smart Museum through February.