Judging by the cascade of critiques for David Fincher’s new film Gone Girl—on everything from the film’s “trashiness” to its “misogyny,”—the movie is but the latest example in Fincher’s filmography that has ended up under fire for a perceived issue with its subject matter. Fight Club is sexist and misanthropic, Se7en is sadistic, Zodiac doesn’t have an ending, and on, and on, and on. Yet none of the critiques have anything to do with the craftsmanship on display, as if technical skill is mere window-dressing in service of The Story. The criticisms of Gone Girl, his shiny, slippery, new psycho-thriller, ring false as ever.

This is not to say that Fincher is somehow beyond reproach (I still have never spoken to a Benjamin Button fan), but rather to observe that every time Fincher deals with material of a potentially controversial nature (which is nearly every time he makes a movie) there are people who cannot reconcile his controlling, clinical directorial presence with the human content of his films. With Gone Girl, as with classics like Fight Club and The Social Network, Fincher’s mastery creates a work whose formal, dramatic, and thematic concerns are barely distinguishable from one another.

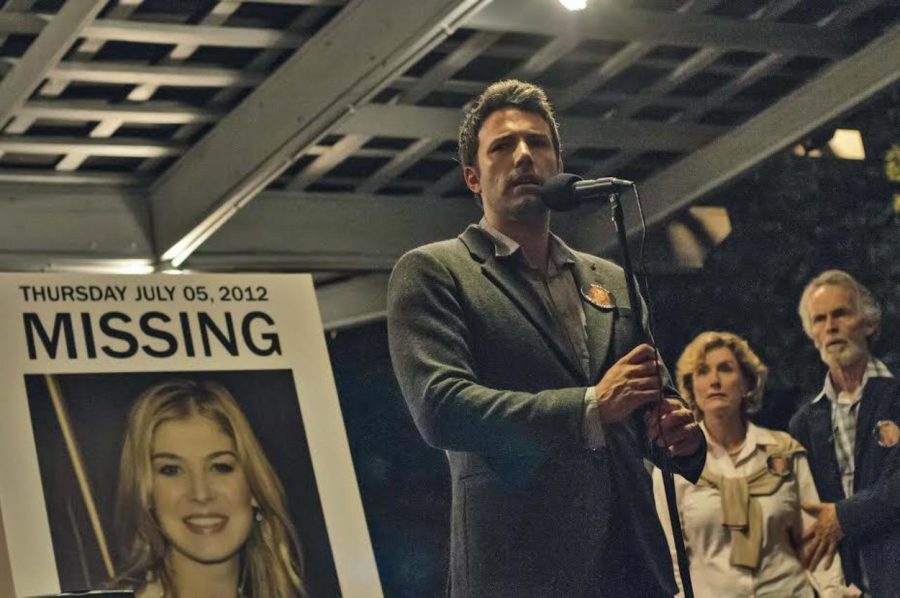

Gone Girl centers on Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) and his absent wife, Amy (Rosamund Pike). Amy is the trust-funded, New York-raised subject of a popular series of children’s books, while Nick is an unpretentious midwestern dude who writes for a men’s magazine. The recession and Nick’s mother’s illness force the couple to move from Manhattan to Nick’s suburban hometown in Missouri. One day, Nick comes home from the bar that he owns to find a coffee table smashed up and no sign of Amy. The hunt is on, but Nick seems aloof and unconcerned with the investigation unfolding around him. Worse, the story of their marriage, unfolded in flashbacks narrated by Amy through her diary, paints the picture of a once-beautiful partnership that dissipated into a domestic situation predicated on emotional distance, repression and fear.

For the first hour, the film operates like a vise, the two narratives tightening on Nick as he looks worse and worse, moving to converge on the question of whether or not he killed Amy.

This section of the film, alternating regularly between the time around Amy’s disappearance and the earlier parts of her relationship with Nick, takes the fastidiously composed digital sheen of Fincher’s last few films to a new level. The film’s Manhattan is completely unreal, Fincher’s version of a fairy-tale; all soft focus, rich, deep colors, interiors that look curated from the pages of the GQ that Nick probably has a piece in. A scene of Nick and Amy walking through a cloud of confectioner’s sugar is both incredibly beautiful and delicate and completely phantasmagoric, both visually and narratively. Meanwhile Missouri is flat and dim, the smooth, calm blandness of the lighting and camerawork like the embodiment of the anonymous suburbia it depicts.

As the narratives progress, our footing becomes gradually unmoored, again both narratively and cinematically, and the result is exhilarating. Fincher, already a master, continues to grow as a filmmaker as he works with his cadre of collaborators in medium-pushing digital filmmaking. Cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth, editors Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall, and composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross are all on hand once again and they collaborate to create a fascinating, rather staggering series of formal double-crosses and reversals. The latter sections of the film allow Fincher to flex his Hitchcock/DePalma muscles without feeling overly indulgent or betraying the story. That is the rare kind of film this is.

Gone Girl is also the type of Fincher film, along the lines of the aforementioned Social Network and Fight Club, in which the authorial voice of either its source-material (like Chuck Palahniuk) or its screenwriter (Soooorrrkkkiiinnn) comes through very strongly via the way the characters speak (in this case, Gillian Flynn provides both source material and screenwriter). It’s the type of movie where basically every conversation between the two leads is a carefully constructed series of witty volleys that both sound good and keep circling back to the film’s thematic concerns. In that sense, it’s something of a confection, and Fincher runs with the sweet fakery in every stylistic direction, throwing curveball after curveball in a way that would be haphazard under the care of a lesser director. But everything in the film is so meticulous on both a micro and macro level that the effect is like being driven around by a racecar driver.

It helps that the cast is so good. Pike, as Amy, is who everyone is talking about, and rightly so. It’s the meatiest role of her career, and she grabs it with both hands. She’s got a great old movie–star face, which Fincher uses like Hitchcock used that of Grace Kelly, Kim Novak, or Janet Leigh. But the part allows her a huge range to play, and she’s a good enough actress to cover all of it while remaining mysteriously human. Affleck, freed from the constraints of likability, gets to indulge the befuddled bro not so deep inside of him. He’s hilarious. His character has almost no agency in the narrative, and his haplessness is charming enough to keep us with him, even as his behavior alienates us. The rest of the large supporting cast is completely stellar, with Kim Dickens, Carrie Coon, Tyler Perry, Patrick Fugit, Neil Patrick Harris, and Casey Wilson all perfectly utilized.

Beyond being a purely enjoyable pulp roller coaster, you might have heard that this movie has much to say about men and women and gender relations and marriage and modern society and all that. This is a partially true, but mostly overblown. The movie (as well as the book) basically takes marriage as a jumping-off point for pointed but surface-level observations about modern, upper-crust American social life. It presents a heightened reality meant as a sort of satire. It doesn’t tear the lid off anything, nor should it. But it has the playfully caustic cleverness about modern life that Fincher’s best films boast. Its observations about gender sting. When Nick complains, “I’m tired of being picked apart by women,” it gets at the tricky satirical balance that Fincher and Flynn are going for here. On the one hand, Nick is pitiable, forced to endure a gauntlet of media criticism and other miseries for the simple fact of being a man in his position (assuming we don’t know what actually happened). On the other hand, his likeness to the normail guy is enough for him to coast through the events of the film while remaining the audience’s main point of identification. The film plays elegantly and subtly with the dynamic between our natural inclination to like Ben Affleck and what that says about how we feel about the handsome men in our lives in contrast to the beautiful women.

This long, complex, and invigorating movie is all bookended by two shots that are composed nearly identically, with Amy’s head framed facing away from us before turning to face us. Sumptuous and cryptic, they might be keys for decoding the film’s multiple layers of blame and meaning. Or they might not; I’m really not sure. I thought of them kind of like the bookends on the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis. The two films are nothing alike in terms of style or theme, but what they have in common is a refusal to talk down to the audience by making their mysteries, existential and otherwise, readily apparent.