Around 4 p.m. on Wednesday, June 3 of this year, nine protesters from the Trauma Center Coalition barricaded themselves inside Levi Hall. After requesting that staff move to other parts of the building, they locked the windows and used a bike lock across the double doors of the building’s main entrance. The protesters refused to leave until President Robert Zimmer agreed to a meeting to discuss a University of Chicago trauma center. Two hours later, members of the Chicago Fire Department broke through the drywall with axes, cut through the bike lock with a power saw, and pried open windows with crowbars. By 6:30 p.m., the protesters had been placed in handcuffs and transported to the Wentworth District police headquarters.

The protest jump-started another round of discussions about the role of student activism on campus. Despite the proximity of finals week (or perhaps due to it), a thread discussing the protest on a popular Facebook group “Overheard at UChicago” accumulated over a hundred comments. In an interview, DNAInfo reporter Sam Cholke described the response to the protest as mixed, pointing out that although many were sympathetic to the cause, others were opposed to the methods employed.

This conversation about the efficacy and appropriateness of the methods of student protesters is a staple of UChicago campus dialogue. On the anonymous social media app Yik Yak, one can find at least a few under-200-character posts about the issue on any given day. On November 20, one post with seven up-votes read, “Real talk, all of this protesting is driving people away from the middle and toward extremes. Just my two cents.”

The platforms of these debates may be new, but the questions are not. The University of Chicago has a long history of student activism, and before there was Yik Yak there were letters to The Maroon. Today’s students may be aware of protests at Edward H. Levi Hall, but many have never heard of the ’60s era protests against Levi himself, or of the hundreds of demonstrations between then and now. Conversations about the effects of student activism at the University of Chicago often lack perspective. Perhaps looking back at this University’s storied history is the best way to begin.

1962: Creating a nuisance

In the spring of 1961, undergraduate David Wolf attempted to rent an apartment with three friends, one of them black. He recalls being “turned down everywhere.” At the time, about 10 percent of Hyde Park’s apartments were university-owned. Wolf’s father, a labor organizer and publicist with contacts in the civil rights community, advised him to test the University by sending black and white students separately to the university-owned buildings to see if they would meet different results.

The following winter, Student Government (SG) and the University’s chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) carried out six such tests; all six resulted in discrimination against black students. In one test, a black student’s application for a University-owned apartment was turned down just 70 minutes after a white student was offered the same apartment. In another case, a black student requested an apartment for $80 to $90 a month on a street he knew had vacancies. He was told that there were no apartments available under $125; soon after, a white student applied for an apartment on the same street and was offered one for $75 a month.

On January 16, 1962, representatives from SG and CORE brought these results to University president George Beadle in a private meeting. The next day’s Maroon headline sent shockwaves through campus: “UC admits housing segregation.” The housing discrimination controversy had begun.

~•~

Faculty and students were already deep into debate about the University’s housing policy when Beadle issued an official statement days later. He justified housing discrimination in some University-held property in the name of long-term “stable integration,” alleging integrating the community too quickly would result in “white panic.” He claimed that the University was “in complete agreement with the stated objectives of the students” and that “the only issue on which there is arguable difference of opinion is the rate at which it is possible to move towards the agreed on objective.”

The students disagreed. Bruce Rappaport, undergraduate and chairman of UChicago’s chapter of CORE, responded that the difference between CORE’s and the administration’s positions was one of methodology as well as rate, as “CORE can never accept segregation as a means to integration on logical or moral grounds.” That night, CORE decided that the next day they would sit in outside of Beadle’s office to protest University policy. Rappaport voiced the commitment of the student activists to their demands: “….we will be prepared to carry it out as long as necessary until we have accomplished our goals—a complete end to segregation in all University owned property.”

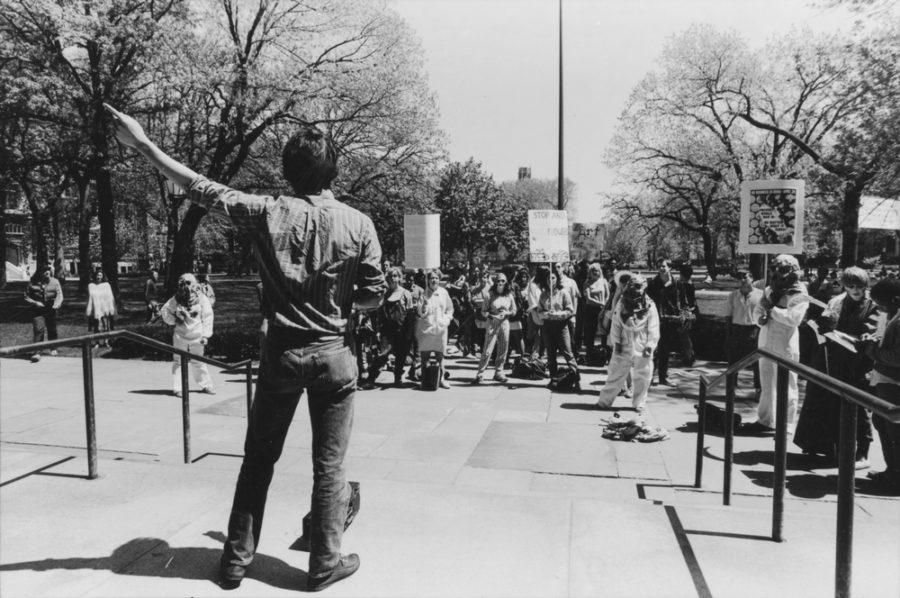

Around noon the next day, January 23, 1962, over 200 students picketed outside the administration building in a demonstration. Current presidential nominee Bernie Sanders, then chairman of the social action committee of CORE, riled up the crowd in his thick Brooklyn accent, saying, “We feel it is an intolerable situation when Negro and white students of the University cannot live together in University-owned apartments.”

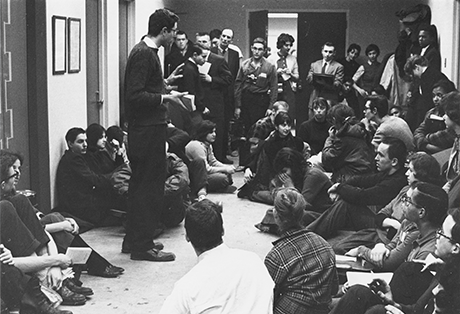

Thirty-three protesters then entered the building and congregated on the fifth floor of the administration building outside of Beadle’s office. Some passed the time by talking or playing bridge; others caught up on reading for their Core classes, diligently attending to On Liberty and The Slave States Before the Civil War. Around 5 p.m., Beadle made his way to his office, greeting the protesters with a smile. When the working day came to an end, administrators requested that the protesters remain only on the fifth floor, and then left the building for the night.

On the second day of the sit-in, Dean of Students John Netherton issued a statement on the sit-in recognizing the right of students to demonstrate, but reminding them that it must be done in an “orderly manner.” To this end, he stated only four students could remain on the fifth floor of the administration building at a time, and that they could do so only between 8:30 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. Mondays through Fridays. CORE had no intention of following these strict guidelines. Anticipating possible action from the administration, Rappaport reminded the other protesters, “Our policy is to be dragged out…every one of you here has supposedly accepted that.”

Rappaport’s reminder proved unnecessary. Although more than four students sat in on the fifth floor for the next several days and nights, the administration took no action against the student protesters. They held informal negotiations with the protesters, including one instance in which Beadle invited student representatives from CORE and SG to his house for a five-hour-long meeting that lasted until 3:30 a.m. Administrators also commissioned a report by three university professors about how best to integrate Hyde Park–Kenwood, and students and administrators issued statements agreeing that creating a grievance committee for discrimination requests would be a good idea.

Nevertheless, no agreement between the students and administrators was reached in these discussions. Administrators were willing to begin formal discussions with student groups about housing policy, but would not acquiesce to CORE’s central demand—that housing discrimination be stopped immediately.

Meanwhile, observing students and faculty remained deeply divided about the University’s housing policy and the efficacy of the sit-in. Several students and faculty wrote letters to The Maroon condemning university practices and standing with the protesters. Lewis Shaeffer, a student, wrote, “Let us suppose Dr. George Beadle was President of the United States on January 1, 1963. He might have said in his Emancipation Proclamation: I hereby declare all slaves to be free on one day per calendar month for one year; then two days per calendar month in the succeeding year, then three days per calendar month in the succeeding year…this progression to continue until freedom is attained for 365 days per year.”

At the same time, many students and faculty found the student protesters too radical. The Practical Reform Organization, a conservative campus political party, received 94 signatures for a petition in support for administration policies, which argued “we are proceeding as rapidly as possible towards a stable, integrated community.” Several professors also decried the protest as ineffective. Ann Swift, a professor in the Department of History, opined, “…picketing is not good except for creating a nuisance. It does not persuade those on the side of the demonstrators and usually antagonizes others.”

As over a week passed and the sit-in continued, it began to make news outside of campus as well. The South Side’s chapter of CORE expressed support for student actions and began their own sit-ins at Hyde Park realtor offices, many of which resulted in arrests and trials. During the same time frame, in three separate instances, black students from the neighborhood’s Ray School attacked white students from the University’s Lab School without apparent motive. Parents of Lab School students alleged that the attacks were a result of heightened racial tension from the sit-in controversy. Meanwhile, the sit-in gained local and national publicity, including a feature in The New York Times.

At last, the sit-in came to a sudden halt on February 5, two weeks after it began. The administration had just released a statement offering joint discussions about integration with members of CORE, SG, the faculty, and several community organizations. While students deliberated their response to the proposal, administration sent a notice warning the students that they had been violating the administration’s rule of four protesters on the fifth floor at a time. Administration demanded students leave the floor immediately and report to Dean Netherton, as “…the failure to do so will result in the automatic suspension of the student’s registration in the University.”

Student protesters finally left the administration building. Beadle issued a statement announcing the final compromise: off-the-record joint discussions. The statement was careful to note that “There would be no votes taken, and the only way a policy would be adopted is by agreement of the University administration.”

At the conclusion of the sit-in, the editorial board of The Maroon argued, “The sit-ins served the valuable purpose of catalyzing University action, and for this they were most worthwhile.” Forty-three years later, in January of this year, author Rick Perlstein interviewed Bernie Sanders for the University of Chicago Magazine and asked him about the compromise that ended the 1962 sit-in. Sanders responded with a weary sigh.

1969: Militant action

Though it seemed dramatic at the time, the 1962 administration building sit-in was tame in comparison to student demonstrations of the late 1960s. As counterculture spread, universities became centers of the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements. Although students at the University of Chicago passionately joined these national efforts, the protest that caused the biggest stir on campus was, in typical UChicago fashion, about academics. The issue at hand was faculty hiring-firing practices.

When Marlene Dixon, a popular left-wing assistant professor of sociology, was not reappointed to her position in 1969, many speculated that it was because she was a feminist and a Marxist. In response to the administrative move, over 400 students voted to take “militant action” by holding a sit-in at the administration building.

The sit-in was rather unpopular on campus. Faculty members wrote letters to The Maroon arguing that Dixon’s reappointment decision was due to inadequacies in her research. Ironically, over 300 students participated in an “anti-sit-in” to protest the original sit-in. Nevertheless, the original student demonstrators held firmly to their demands, announcing, “Sitting in at the administration building halts the normal functioning of the university; therefore forces the administration and faculty to deal with us and our arguments. No less militant action would achieve these results.” To an extent, the students were right—two weeks later, the administration offered Dixon a one-year extension of her contract. (She ultimately turned it down.)

However, the victory came with costs. By the end of the quarter, the administration had expelled 42 of the students involved in the demonstration, and suspended another 81. If administrators hoped this would quell protests, they were wrong. Soon afterward, student demonstrators marched to University president Levi’s home with a petition for disciplinary leniency. They pounded on his doors and windows and called his name; when they realized he wasn’t home, one student broke the glass of the outside door, crawled in to unlock the door, and stapled the petition to the inside door. After these students were also suspended, students set off stink bombs in University buildings, organized a boycott of classes that 70 percent of students participated in, and carried out a hunger strike on the main quad. None of these actions changed the punished students’ sentences.

Peter Draper, A.B. ’75, was a student activist in the college during the early ’70s. When asked whether the expulsions of the students involved in the 1969 protests discouraged students in the following years from pursuing similar methods, he grins. “I never remember anyone saying ‘let’s occupy the administration building again,’ but I don’t think that made people think that they shouldn’t protest.”

The expulsions certainly didn’t make the 1969 protesters themselves regret their actions. One reporter for The Maroon interviewed a few expelled students in 1983. When asked about their actions, they unanimously stood by the decisions they made in 1969, agreeing that if they were to relive the situation, they would have “kicked out the administration immediately…tried to close the school down and use more dramatic tactics.”

1980s: A failed attempt

Students in the 1970s and 1980s continued to be involved in protests about a host of issues—nuclear disarmament, federal abortion restrictions, LGBT rights, foreign policy, and more. Nevertheless, the general consensus is that the 1960s marked the height of the influence of student activists. Sahotra Sarkar, Ph.D. ’89, was a student activist during the late ’80s. He recalls political cartoons of the ’80s that satirized student protesters as excessively tame, “intentionally not as disruptive as those in the 1960s.”

Sarkar was one of the leaders of UChicago’s anti-apartheid divestment movement at UChicago in the 1980s. The national divestment movement aimed to put pressure on the government of South Africa to end the apartheid—the system of racial segregation by encouraging universities to divest from companies that did business there. The national movement has been singled out by some academics as the most important instance of student activism post-1960s.

At the University of Chicago, the divestment movement’s demonstrations were nowhere near as disruptive as the 1969 sit-in. Sarkar remembers this as a deliberate decision of the University of Chicago movement. He says, “After a lot of talking back and forth…it was decided that we did not want to commit civil disobedience because we did not want to divide the community.”

The movement was successful at not dividing the community—Sarkar estimates that about 90 percent of students supported divestment. Letters to The Maroon on the issue from the late ’80s by professors and students alike are largely uncontroversial, nearly unanimously urging the Board of Trustees to divest.

And yet, the University never fully divested from South Africa. Many of its peers, especially those that had more disruptive protests for divestment such as Columbia and the University of California schools system, did. In 1990, the Apartheid ended, bringing a conclusion to a decade long student movement that never succeeded. It’s not surprising, then, to hear Sarkar hypothesize on current-day divestment campaigns, “I don’t think they have any chance of success.”

2015: Diverging narratives

Today’s student activists are more optimistic about their own chances of success. From University of Chicago Climate Action Network’s campaign for divestment from fossil fuels to the South Side Solidarity Network’s Campaign for Equitable Policing, student groups continue to campaign for changes in University policy. One such group, Phoenix Survivor’s Alliance (PSA), advocates for sexual assault survivors.

In May of 2015, student demonstrators from PSA marched to Levi Hall holding signs and chanting, “Rape culture is contagious, come on Admin be courageous.” They delivered a list of five demands to administration, one of which urged the University to provide more comprehensive education on consent, federal Title IX rights, and other sexual assault issues during O-Week and for grad students, and another which requested that information regarding the rights of sexual assault victims be posted online in an easily accessible format. The group loudly chanted on the second floor of Levi Hall outside of the Office of Student Life until a dean-on-call picked up their list of demands and promised to deliver it to Dean of Students Michele Rasmussen.

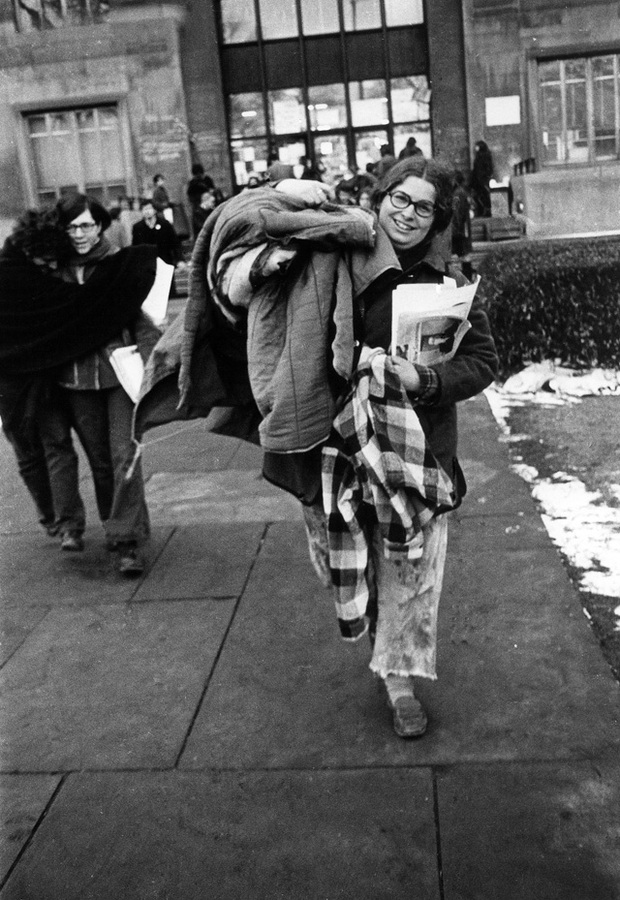

The next week, PSA, along with other student activist groups, held a senior sit-in at Levi Hall with the same demands. Graduating seniors wearing caps and gowns refused to leave the building until they were told they would not graduate if they stayed. At the same time, Veronica Portillo Heap, A.B. ’15, co-founder of PSA, filed a federal complaint against the University for not meeting Title IX’s requirements for training students about sexual assault policy.

In the beginning of the 2015–2016 school year, the University made changes to its sexual assault education program. Now titled “UMatter: The O-Week Chicago Life Meeting,” the program was changed from a discussion to a presentation in order to explicitly define the University’s policy on consent, the rights of sexual assault victims, and the investigative process. Moreover, an optional sexual assault prevention seminar was added to graduate student orientation. Finally, the University launched the UMatter website, a user-friendly central location for information and resources regarding sexual assault, at the end of this last summer.

Were these changes a result of the actions of student demonstrators? Heap believes they were.

The day after the senior sit-in, she received an e-mail from Rasmussen inviting PSA to a series of conversations about the progress the University was making to meet the PSA demands. Before the two spring protests, Heap says, PSA members had several meetings with Rasmussen and other administrators about the University’s sexual assault prevention, until finally administration refused to have any more meetings with them. According to Heap, at each of the previous meetings, administrations “told us that they would not do anything and that they were compliant and that there was nothing wrong.” Heap cites the combination of the two protests, the Title IX violation complaint, and viewpoints articles she wrote for The Maroon as the catalyst for the University’s changes.

Rasmussen disagrees. She says, “Because of the timing of the school year, a lot of the actual planning work for O-Week doesn’t happen until late spring, but we knew starting in the fall of 2014 that there were things we wanted to do differently during 2015 O-Week …. And we also knew that we would be developing a UMatter website. That website only went up in the late summer because summer is when we had the time and the resources to develop the website.” She says that administrators took PSA input into account when building the UMatter website. However, she stands by the administration’s previous stance, saying, “Those changes were not due to being in violation of Title IX.”

“Direct action never works…until it does”

The Levi Hall sit-in this past spring was only one action in a half-decade long campaign by the Trauma Center Coalition (TCC), the group of community activists and students that advocates bringing a Level I trauma center to the South Side of Chicago. During the same weekend as the Levi Hall sit-in, the group held a die-in at an alumni awards ceremony in Rockefeller Chapel. Earlier that month, they marched to Zimmer’s house. In March, they blocked off Michigan Avenue during a University fundraising event downtown. Several campus activists not affiliated with the TCC describe the group’s actions as more risky and disruptive than those of other campus groups.

This summer, the University of Chicago announced a joint partnership with the Sinai Health System to establish a Level I adult trauma center on the South Side. The announcement made no reference to the TCC or any recent protests. When asked if the spring protests had any role in the trauma center decision, Zimmer says, “One always listens to what’s going on around one, but I think the fundamental question was what are the set of healthcare needs of the South Side…It’s a whole set of decisions that were made in a very complicated environment.”

Tristan Bock-Hughes, a third-year in the college and a member of the South Side Solidarity Network, coordinates demonstrations with community members. When asked whether he thinks UChicago’s joint partnership is a response to the TCC protests, he pauses and says, “Direct action never works…until it does. No power will ever want to admit that it was these people yelling at me who made me uncomfortable and then I changed something…The alternative is saying they made us look weak and we had to change.”

For Bock-Hughes and other student activists, the question is not whether nonviolent protests can work, but whether the risk of expulsion or arrest is worth it. He describes the necessity for a movement to pick the right target and the right method, usually “media shaming or hitting them in the wallet.” In his words, “For the most part…if you have a demand and hit someone in the right way you’ll see something come later.” He furthers, “The effectiveness of how much you are going to be able to move your target is pretty directly connected to how high risk this is going to be for you.” He then qualifies, “…if it’s done right, and if it’s nonviolent.”

Bock-Hughes’s comments speak to the central dilemma of determining the effects of student protests. For each student movement, there are two vastly different narratives—one in which the administration makes decisions independent of student protests, and one in which it is moved by student actions. With all the exogenous factors that influence a University’s decisions, it is difficult to draw direct lines between a student movement and an administration’s action.

There is often a backlash against protest movements that are “too disruptive” or a “nuisance” to the everyday lives of students. Whether in The Maroon or Yik Yak, whether in statements or in actions, students and administrators critique demonstrations that are especially at high-risk.

Yet history suggests that protests can work, and high-risk protests can be particularly effective. There are stories of protests that were not high risk, such as the anti-Apartheid campaign, that did not see results. There are stories of protests that were excessively high risk, such as the 1969 administration building sit-in, that did see results at high personal cost. And then there are stories such as the 1962 housing discrimination sit-in—stories of student protesters on the moral high ground, taking moderately high level of risks, with only debatable results.

We will never know exactly what was said in the off-the-record conversation that ended the 1962 administration building sit-in. All that we know is that some time in the past 50 years, the University stopped discriminating against black students applying for off-campus housing. It’s possible that the sit-in’s contribution to this was negligible; it’s similarly likely that some of the student movements of today will fail to ultimately affect policies.

But there is also a very real possibility that the risks student protesters take will pay off, that their words will be heard, that their defiance will create change.