Some University of Chicago faculty members have presented objections to the Obama Presidential Center (OPC), contending that the Obama Foundation’s plans violate Frederick Law Olmsted’s intent for the park’s design even with one of the Foundation’s guiding principles being to “honor the vision of Frederick Law Olmsted.”

One-hundred-and-eighty-two University of Chicago faculty members have signed an open letter concerning the future of Jackson Park, expressing their desire for the “Obama Foundation to explore alternative sites” for the OPC.

In contrast to the faculty letter’s concerns, a University spokesperson said, “The Obama Presidential Center has the potential to be a powerful catalyst for economic development, civic engagement, and cultural opportunities across the Chicago region, especially in the South Side neighborhoods. As with all issues, University of Chicago faculty members are free to express their individual views and engage in discussions in any format they wish.”

The letter first highlights faculty members’ frustration with a planned above-ground parking garage which they believe takes away green space and parkland, a decision they conclude Olmsted would have fought against. Frustration over the parking garage location led the Obama Foundation to reconsider plans. On January 8, the Foundation conceded to public outcry and announced they would move the parking lot to an underground location within Jackson Park.

Jonathan Lear, John U. Nef distinguished service professor and an organizer of the faculty letter, credited the announcement as a victory for the community but remained skeptical of the OPC as a whole.

“The underground parking garage does address one of our concerns about the misuse of a historic public park,” Lear said, “but the other serious issues raised in the letter—the relative lack of opportunities for economic development, the huge burden to taxpayers, and the unprecedented size of historic public parkland to be given to a private entity—remain to be addressed.”

Nearly every faculty member who discussed the concerns raised in the faculty letter with The Maroon mentioned that the Center’s plans disregard the original intent of Frederick Law Olmsted.

The Obama Foundation maintains that Olmsted’s vision acted as a guide in the development of the park and believes that Olmsted would have approved of its changes in his design as part of an evolving landscape. “Jackson Park of 2018 is far different than Jackson Park of 1870,” a spokesperson from the Obama Foundation said. “The story of the park tells an interesting evolution in response to changing circumstances more than it represents the pure intentions of Olmsted and [collaborator Calvert] Vaux.”

In the Obama Foundation’s perspective, the intentions of the museum align with Olmsted’s values. “Olmsted was an influential advocate for social causes in his day. It is fitting that a cultural attraction that celebrates the significant accomplishments of African Americans, which will become a global destination for civic activism, would be located in one of his parks,” the Obama Foundation said.

Many community members see Olmsted’s vision having little room for the evolutionary decisions the OPC would make in redesigning the park. “The plan will destroy Olmsted’s design by the use of the park for buildings,” Lucia Rothman-Denes, A.J. Carlson Professor of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, said. “They are killing Olmsted’s vision, but what they are actually killing is a place that supports wildlife.”

The Obama Foundation refutes the idea their plans destroy space for wildlife. “The OPC buildings occupy less than three acres out of Jackson Park’s current 500 acres, in part because of the decision to build a vertical tower rather than a horizontal museum experience so that we could preserve parkland and minimize our footprint,” the Obama Foundation said.

The faculty letter’s focus on the OPC’s disregard for Olmsted’s design was a factor which precluded Martha Nussbaum, Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics, from signing the letter.

“Olmsted should not be fetishized,” Nussbaum told The Maroon of her arguments with letter organizers. Some parts of his plan were silly, such as turning the Midway into a canal and having gondolas going up and down.”

Director of the Language Program in German and Director of the Chicago Language Center Catherine Baumann, who signed the faculty letter, also admitted the over-commitment to Olmsted’s design in the faculty letter. She suggested the OPC plans may actually recreate parts of Olmsted’s design, such as the OPC’s civic spaces within the forum and large public green spaces to promote, as Olmsted characterized it, the “harmonizing and refining influence” of parks.

Further acknowledging Baumann’s claim, the Obama Foundation frames their design as “consistent with the best and most revered historical visions for Jackson Park—even more than in its current fragmented configuration.”

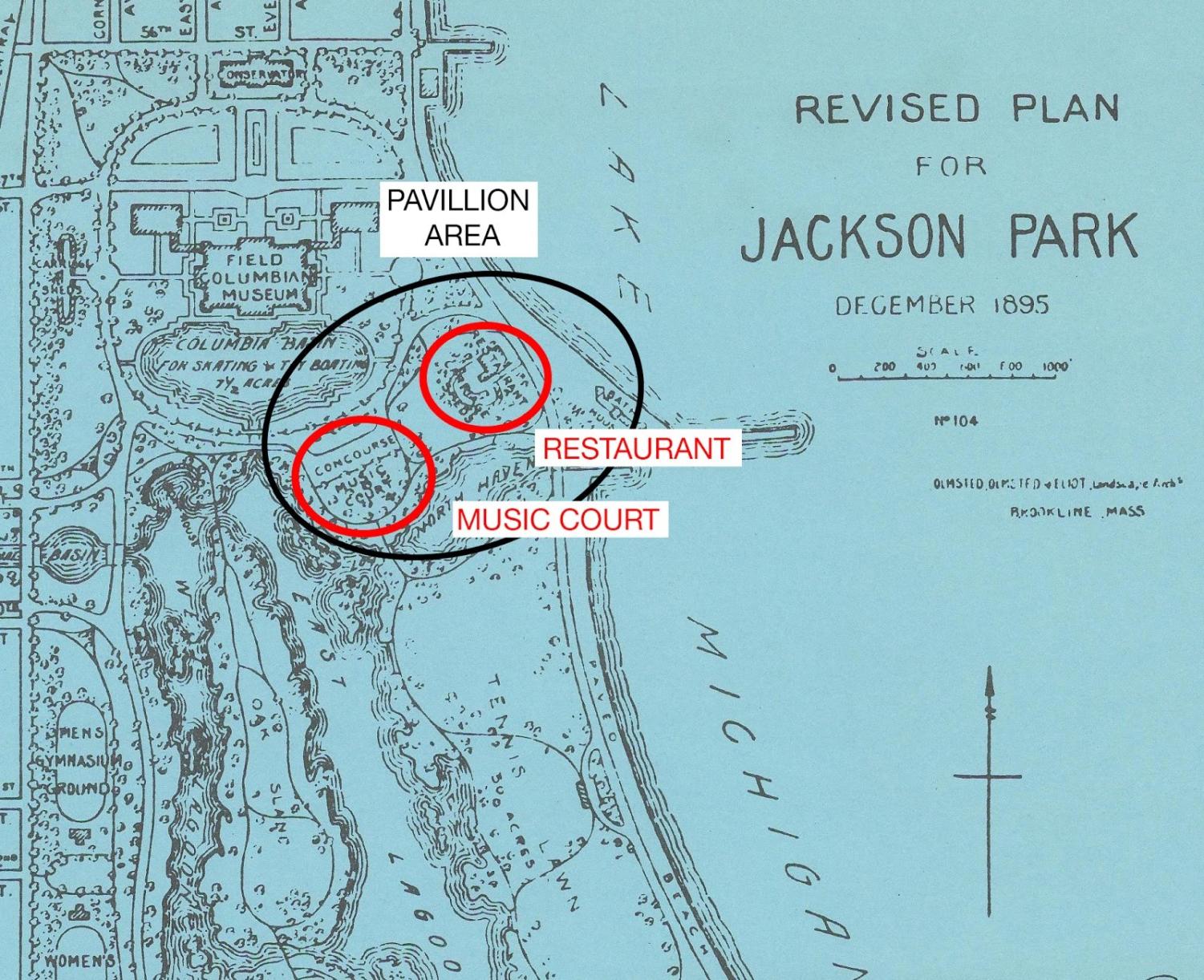

Visiting the original park plans from 1871, revised plans for the 1892 World’s Columbian Exposition, and the final 1895 Revised Plans of Jackson Park—finished by Olmsted’s son—provides a comparison between Olmsted’s objective plans and those proposed for the OPC.

An initial comparison between these plans and the current OPC plans reveal definite links between the designs. The OPC plans include a plaza which surrounds the museum, forum and library building and according to the Obama Foundation “will host performances of all types, including celebrations, events, or markets and fairs.”

Olmsted historian Victoria Post Ranney credits Olmsted’s original version of Jackson Park, then called South Park, as containing similar features. “Olmsted planned a pavilion: a large refectory building, where meals would be served, and in front of it a large area covered by trellises and surrounded by galleries or roofed promenades,” Ranney said. She also describes Olmsted’s intent for concerts to take place in the pavilion while guests could enjoy refreshments.

Upon sharing original maps with the faculty letter’s organizers, W.J.T. Mitchell, the letter’s Olmsted historical advisor and professor of English, art history, and visual arts also described the faults of corollary conclusions formed by the maps and the necessity to consider the park’s elaborate history.

Originally designed in 1871, the park’s official first plans never came to fruition after the Great Chicago Fire destroyed all of the park’s contractual documents and plans—although the actual parkland remained unscathed. Due to financial concerns, planners abandoned Olmsted’s grandiose vision for waterways and canals in South Park, and the plans were restructured.

South Park went through major transformations again for the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. After the Exposition, the park burned down in 1894 and was rebuilt with a final revised plan designed by Olmsted’s son in 1895.

Jackson Park’s tumultuous past complicates which iteration of plans one should refer to when considering the park’s “original plans,” making it difficult to follow community members’ claims about Olmsted’s vision.

Additional historical context provided by descriptions of Olmsted’s intentions for South Park do not display the kind of dedication to pure, natural spaces in the park, which the faculty letter and many community members assume.

In her book Olmsted in Chicago, Ranney writes: “Olmsted predicted that South Park would soon be the center of a populous and wealthy district…. To be well adapted to such habitual use, he decided it would need a much greater variety of features and accommodations.”

The faculty letter’s final charge against the OPC plans argues that closing Cornell Avenue will cause major traffic problems and changes Olmsted’s design, which includes the street. Visiting the original maps confirms the presence of a roadway inside the park that today constitutes Cornell. The roadway originally allowed carriages to travel through the park for guests to enjoy, far from the commuter highway that it has evolved into today.

The Obama Foundation notes Cornell’s functional change stating, “The addition of Cornell Drive through the park has resulted in a fragmented park that is disconnected from some of its greatest assets—the lagoon and Lake Michigan.”

“We see our project as a continuum of the park’s history,” the Obama Foundation said. As OPC plans become final, the Obama Foundation remains confident in its potentially positive outcomes for the community.