UChicago takes pride in the efforts of its civic engagement department to give back to the surrounding community, programs like the Neighborhood Schools Program or UChicago Local initiative. However, if the University really wants to build a partnership with the South Side community, it needs to give locals a say in how those resources are distributed. Setting up a community board attached to the Office of Civic Engagement (OCE) and establishing a Reparative Justice Center—both endowed with autonomous leadership, true authority, and adequate funding—are two necessary steps to ensuring that’s the case.

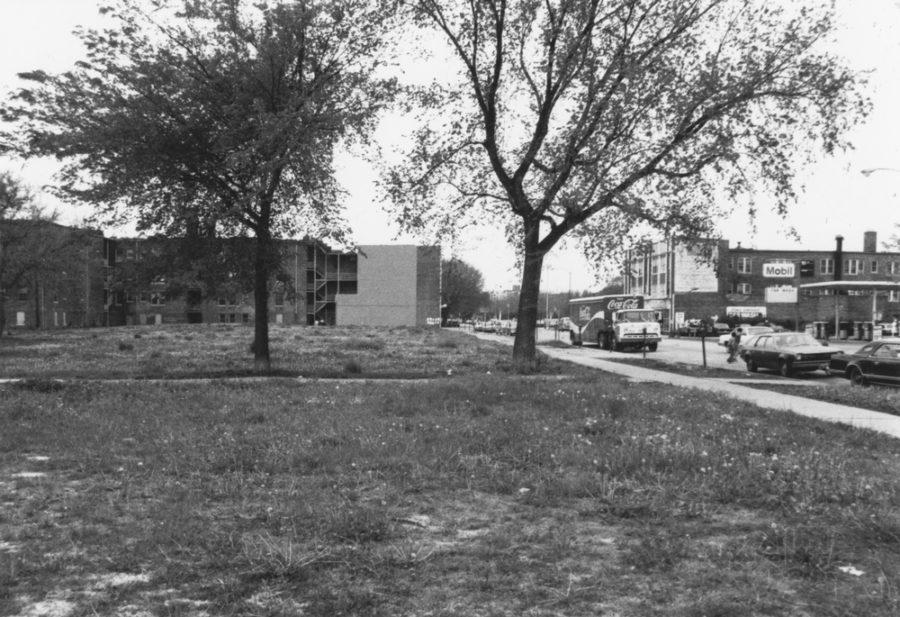

Since its founding, the University of Chicago has worked against the interests of its Black neighbors in order to enrich itself by privileging the interests of its white community members, “revitalizing” and reorganizing the South Side. The history of our primarily white institution deliberately separating itself from the South Side, whether that be through isolationist campus architecture or destruction of Black neighborhoods under the guise of “urban renewal” projects and the South East Chicago Commission, is a legacy which undergirds the relationship between campus and the South Side community today. It is UChicago’s responsibility to acknowledge this legacy and actively work to dismantle it by redistributing power to the locals, particularly those Black Southsiders whom they have so long sought to silence and displace.

The appointment of Derek Douglas, a former South Side organizer, to vice president for civic engagement and external affairs was a step in the right direction towards letting those familiar with the needs and demands of local residents guide the University’s engagement with such issues. The next step is creating a lasting, institutional body that positions our neighbors front and center in the decision-making process, ensuring their needs are heard and accurately met so that a true partnership can begin being built between the University and the South Side.

Deborah DeVaughn, a Chicago Public Schools teacher, has spent most of her life on the South Side, but despite growing up less than two miles south of the Midway, she said the University has always felt distant to her. She never saw many avenues into the University community and when she did they were one-off events that didn’t go far for her in forming a relationship. Still, DeVaughn expressed practical optimism for the idea of a partnership between the University and the surrounding South Side neighborhoods; she listed off the top of her head a number of ideas for programs and initiatives, most with her students in mind, that the University could provide to support its neighboring communities.

However, DeVaughn had clear criteria needed to achieve such a relationship: regular and substantive engagement through the incorporation of Southsiders into the University’s everyday functioning. “If you don’t have that exposure, you don’t have a relationship and you don’t help grow people who would want to get to know and be a part of the University.”

Currently, OCE has a working group composed of around 50 community stakeholders from the nine South Side neighborhoods the University interacts with, but for their voices to truly be honored they need to be given real bargaining power. A community board with the ability to help shape OCE programs at every step, composed of local activists, organizers, and enthusiastic Southsiders like DeVaughn, could go a long way toward making these programs more effective at meeting the needs of the people they are intended to serve.

However, in order to truly start to repair the damage done by more than a century of resource deprivation, redlining, and the University’s original ties to slavery that the historians from the Reparations at UChicago Working Group (RAUC) have identified, OCE will not be enough. As RAUC argued in an interview with the Maroon Editorial Board, reparations require the University to honestly acknowledge its historic role in perpetuating structural racism on the South Side, and to relinquish control over how the money it must invest in reparative work is used.

A Reparative Justice Center, funded by the University and governed by a coalition of community organizations, offers the opportunity to leverage UChicago’s wealth to make a material difference in the lives of the people it has historically harmed.

Discussions of reparations on college campuses often point to the example of Georgetown, which established a policy in 2016 to give admissions preference to the descendants of enslaved people sold by the school’s founders, and whose students established a reparations fund in 2019 to benefit those descendants. UChicago has yet to fulfill this very basic step of recognizing its racist foundations and meaningfully contending with them, as Georgetown has done.

The first step towards this would be meeting the demands of the More Than Diversity campaign and creating a department for Critical Race and Ethnic Studies. Such a department would enable faculty and students to interrogate the University’s own history, and partner with a Reparative Justice Center to explore ways to move toward a more equitable future. But UChicago also has the chance to go beyond the examples of its peer institutions, and set a new standard for universities reckoning with their violent pasts.

“As far as I know, it's always been a top-down [process], how can the University provide leadership and do certain things it wants to do, maybe consulting and kind of asking permission,” said RAUC member Guy Emerson Mount. “But I think that the model that we would like to see happen and that communities would like to see happen is that the community is kind of in control of not just the truth telling process, but the reparative process, with the assumption being that communities know what communities need.”

In an interview with The Maroon, Douglas mentioned a survey that showed the more interaction community members had with the University, the more positive their perception was. If it is OCE’s goal to improve the University’s relationship with the South Side, then they must begin to bring community stakeholders into the fold. In recent years, OCE has worked to support its neighbors by funding the initiatives the University decides it should offer to the South Side. But under such a method, the University will never meet the needs of community members and activists or allow them to take the lead in determining how to repair the damage the University has done to their communities. Meanwhile, these groups will continue to speak over one another, maintaining an age-old divide. Only once Southsiders have a leading role in the University can we begin to see activists and administrators speaking the same language.

Transforming the University’s community outreach through a two-pronged approach of a Community Board, which directs and approves OCE initiatives, and a Center for Reparative Justice, whereby the University financially supports the needs of Southsiders, would not only begin a partnership to heal the historic rift between the South Side and UChicago, but also lay the foundation from which to meaningfully approach the University’s historic harms and their present-day consequences.