Veni, Vidi, Vici, Or How I Claimed a Space in Classical Studies for Myself

Even though Classics is often used to justify modern-day bigotry, I helped create a more diverse and welcoming field in my four years here.

May 30, 2022

Content Warning: The following submission contains mentions of sexual assault.

Whenever I tell people that I study Classics, I am often met with the same barrage of questions: Why do you study dead languages? What will you use that for? And of course, not to be forgotten is the ever-promising “what jobs can you even get with a Classics degree?” While these remarks bothered me as a first-year, over the years they’ve come to be comforting reinforcements of why I chose the Classics major. Contrary to popular belief, Classics is not dead, but rather an intrinsic part of everyday life. Throughout my time at UChicago, by studying Classics, I have found that I’ve been able to open a connection to the past, reviving its memory and learning the many lessons it brings.

Initially, I continued a seven-year-long study of Latin for the simple reason of wanting an early class to drag me out of bed every morning. I mistakenly thought I would be comforted by the familiar verse of Virgil amid the unfamiliar newness of college. However, my comfort was soon replaced by a startling awareness of the parallels between fabled myths and modern-day events. The injustice of ancient rapes and violations was revived in 21st-century newspaper headlines. While translating the ethnocentric narrative of Julius Caesar’s De Bello Gallico, I simultaneously witnessed the rise of xenophobic hate crimes during the pandemic. I studied the Roman civil wars against the backdrop of the January 6th Capitol insurrection. My study of the classics was not an easy voyage, but rather an eye-opening exploration of how our world is rooted in a historic cycle of the same devastating mistakes.

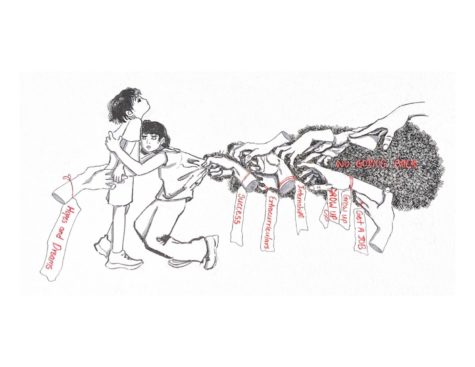

Despite my love for ancient history and literature, I was hesitant to declare a Classics major. In modern times, the field of classical studies is mired in controversies regarding its use to justify racially charged crimes, xenophobic values, and a hateful culture of non-acceptance. As a woman of color, I was devastated by the realization that my academic hearth was a field used by white supremacists to justify bigotry and violence. During my second year, though, my hesitance was met with the realization that the classics did not belong to those hateful views.

In spring of 2020, during the early days of the pandemic, I began an independent translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses at my family’s home in New York. Sitting in the living room, I began my work in front of a sculpture of Apollo and Daphne that had been placed on the coffee table in homage to my brothers’ and my high school study of Latin. The sculpture is a replica of Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne, a Baroque-era sculpture aestheticizing the moment Daphne transforms into a laurel tree and escapes Apollo’s grasp. As I unraveled lines of verse, I soon realized that Ovid was lamenting Daphne’s plight, using poetic forms like chiasmus to emphasize and condemn Apollo’s sheer power over her while also celebrating her strength in choosing to forgo a human form to express agency.

By reviving the original lines of Apollo and Daphne, I learned that our society has lost the story’s message in translation. Bernini, among many Renaissance and Baroque thinkers, romanticized the story of Apollo and Daphne despite its horrific subject matter: a girl moments away from being raped. Apollo and Daphne is not the only example of a translation gone wrong. The historic proclivity for idealizing the classics has obfuscated the valuable lessons we can learn from the field. Moreover, I soon recognized the role women had in recasting the entire field, studying the works of contemporary classicists like Alice Oswald, Anne Carson, and our own faculty at UChicago. Between office hours, coursework, and even research with instructors like Michèle Lowrie and Catherine Kearns, I was challenged to stake my own claim and space in classics. Whether it be the encouragement to apply for fellowships or the introduction to new and exciting interpretations of classical literature, these professors wholeheartedly welcomed me into the classics community. I became determined to contribute however I could to this growing tradition of making classics a more inclusive and diverse space.

I pursued my final year as a Classics major with this idea in mind. Through my B.A. thesis project, I sought to champion the growing accomplishments of female classicists alongside using classical literature as a mechanism to commemorate the dead. I studied the Iliad through the contemporary lens of Alice Oswald’s Memorial, an equalizing translation of the Iliad, and the Say Their Names movement, a social memorial for Black victims of police violence. In doing so, I revived classical literature’s immense capacity for memorializing and democratizing the dead, while also working to counter the racially exclusionary contemporary applications of Classics. Throughout this year, I also worked with a team of fellow Classics majors to launch Animus, the University’s first undergraduate classical studies review journal. In this space, we were able to work with writers from universities around the world, creating a platform to promote diverse and underrepresented voices in Classics.

As I leave UChicago, I know that I will not leave the lessons from Classics behind. While I head into a consulting career that seemingly has nothing to do with Classics, I will take with me the awareness and skills to make my professional journey an inclusive one. I am proud to have taken a small step in making one of the most exclusionary and misused academic fields a bit more welcoming and diverse.

Brinda Rao is a fourth-year in the College.