Beyond its academic intensity and trademark quirkiness, the University of Chicago stands out for its unwavering commitment to freedom of expression. The Chicago Principles, along with the Kalven Report, are two documents that define UChicago’s unwavering commitment to free expression. The Chicago Principles describe the University’s commitment to free speech, and the Kalven Report asserts the importance of institutional neutrality.

The Kalven Report has previously been applied in discourse on various issues ranging from divestment to global conflicts. Since March 2024, Jill Glick, a pediatrician at UChicago Medicine and founder of the University of Chicago Medicine Child Advocacy and Protective Services Program, has been pushing the University to take a stance against legislation targeting routine practice in child abuse medicine. The case raises concerns about institutional neutrality interfering with medical practice.

The University denied Glick support in standing against the Protecting Innocent Families Act, a piece of legislation that would protect the right of families of child abuse victims to know when their child is being examined by a medical professional contracted by the Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS). With the introduction of this amendment, families would need to be informed when a pediatrician is involved in a Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) investigation. The bill would also empower these families to seek a second medical opinion on whether the child suffered abuse or neglect. According to the bill, these measures ultimately aim to reduce the overreporting of abuse or neglect caused by hasty misdiagnoses.

According to Glick, the bill, which was drafted by defense attorneys, seeks to limit the power of pediatricians in these cases. “Defense attorneys are not neutral. Defense attorneys are trying to defend their defendants, and… their goal is to ensure due process,” Glick said. Glick implied that defense attorneys have a vested interest in preventing pediatricians—neutral scientific experts—from testifying in child abuse cases, which is reflected in the bill.

However, Glick said the amendment would also impact how pediatricians practice medicine. “[The amendment] told us specifically how and what we have to say to our patients when we evaluate children and families,” she said.

Glick argues that when politicians or legislators start controlling how medicine is practiced, the University must step in. “Our mission is to provide medicine, and if, in fact, there is legislation that is challenging best practice, we need to stand up, and the University needs to stand up,” she said. “[The Kalven Report], in my opinion, is a cloak of scholarly cowardice.”

On March 13, 2024, Glick asked UChicago to submit a witness slip representing the University. A witness slip is an individual or community’s response to a bill. The individual or community submits a response to the Illinois General Assembly before it is considered by a House or Senate committee, which will indicate an offer to testify against the legislation. According to Glick, the University denied her request, citing the tenets set forward in the Kalven Report. Glick saw that other hospitals, such as Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, had put in witness slips. She “felt very alone and very isolated and betrayed” and believed that her work was necessary and that the bill would do irreparable harm to both her work and her patients’ well-being.

“The University did not take an official position on the bill that you mention. Consistent with the ideas articulated in the Kalven Report, individual faculty members are free to engage in advocacy on this and other issues if they choose,” a University spokesperson wrote in a statement to the Maroon.

Glick found the goal of institutional neutrality valuable, especially in research and the classroom. However, she thought the University’s prioritization of institutional neutrality became problematic when it came to the commitments of medical professionals. “The whole purpose of the University of Chicago… is the idea that we’re supposed to create new knowledge to improve humanity in all the different facets,” she said.

“Our commitment is to the well-being of our patients. Therefore, if there’s something that impedes our ability, it is our responsibility as physicians to advocate for our patient.”

Glick did not think that the Kalven Report itself is problematic. Instead, she thought that the problems come from the “opacity” of the University’s application of the Kalven Report and the fact that the Kalven Report has not been updated since its creation in 1967. Glick underscored that the Kalven Report needed to clarify its requirements of the University so that its applications could be more strictly delineated.

“When something legislatively comes up that’s anti-medicine, the University has to have an open forum and discuss Kalven’s application,” Glick said. She believed that this discussion should have happened when she went to the University asking for help in her advocacy against the Protecting Innocent Families Act.

Although the original bill did not pass, it has reappeared in the House as HB3169, an amendment to the Abused and Neglected Child Reporting Act. Glick is now working to get the University to oppose this bill.

As Glick’s experience highlights, the applications of the Kalven Report have not changed over time. Jamie Kalven, a writer and human rights activist championing his father Harry Kalven Jr.’s treatise on free speech, believed this interpretation needs an overhaul. Specifically, Kalven believed the application should include a more structured and documented deliberation process.

“The committee was trusting to the future the task of building such a deliberative process. I think what happened in fact is that very quickly that presumption against public statements hardened into creed,” Kalven said, pointing to Glick’s experience as evidence.

Kalven interpreted the spirit of the Kalven Report as intending “to create optimal conditions for free and robust exchange of ideas within the university and optimal conditions for individuals within the university community to participate in political discourse more generally.”

According to Kalven, the document was created as a “point of departure” for the community to grapple with political issues. While it sets in place the presumption that the University will not take a position on a public issue, Kalven thinks that rebuttals and exemptions could be made to that assumption.

The Kalven Report, he believes, is only the precursor to deepening knowledge of the free speech principle with subsequent application and interpretation. He compared it to common legal development, where after each case, “there’s a deepening understanding, a deepening of knowledge of the principle as it is tested by concrete situations. In a way, it’s a dialogue between the principle and different fact situations—a process by which experience and knowledge accumulate.”

According to Kalven, implementing the Kalven Report as an anchor for the creation of knowledge requires two things: transparent documentation and community involvement.

“There’s no written record of decisions made under the Kalven Report, you know. I’m quite sure drafters did not quite anticipate that application of their recommendations would be a matter of administrators voting up or down.… Think of how interesting it would be now if there was a rich history going back half a century of different deliberations that were documented,” he said.

Kalven said that in the absence of such documentation, those within the University who enforce the Kalven Report are under no burden to give a reasoned explanation for why they arrived at the conclusion they did. “So what my father, I think, intended as an open invitation to have difficult conversations has often been deployed as a shield against having those conversations.”

Ultimately, Kalven believed that the University needs to be “socialized” into such a deliberative process. He believed that the more crucial concern in Glick’s case was not whether submitting the witness slip was the right or wrong decision, but rather why there hadn’t been a deliberative process with the University in making that decision.

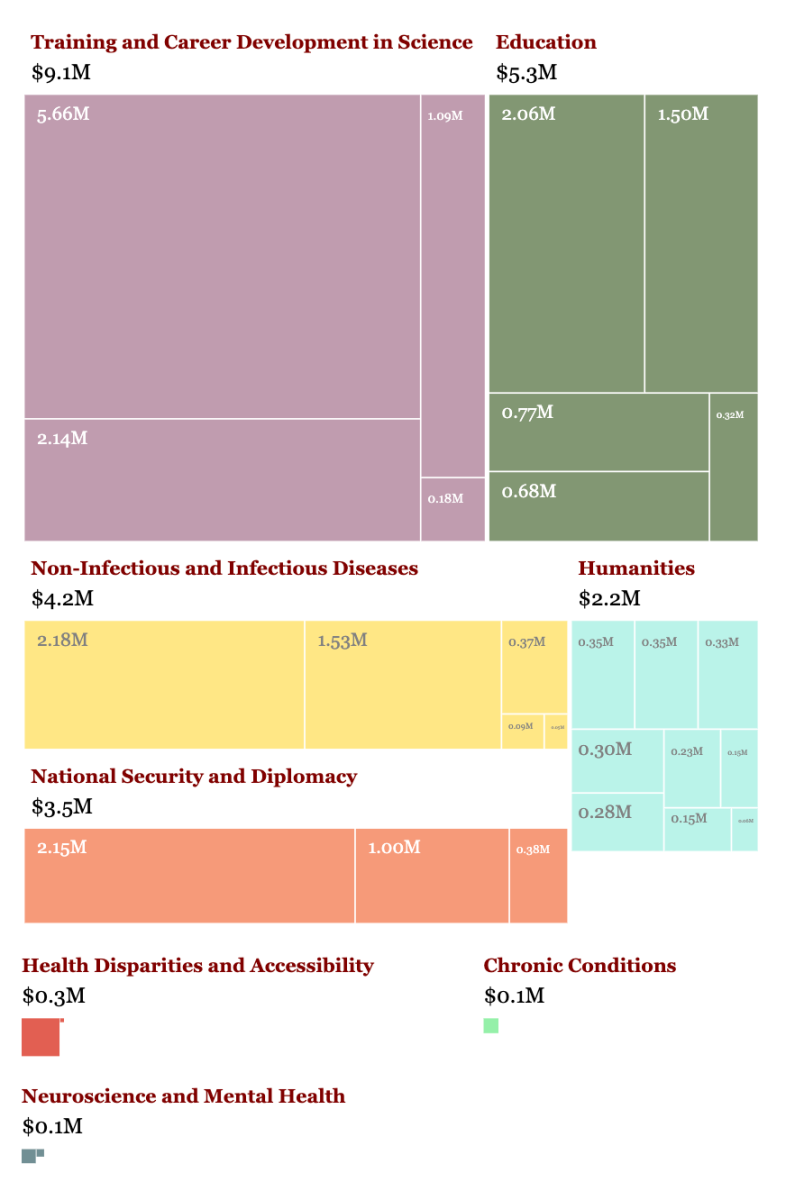

Glick believed that the time had come for the University to step into politics. She felt this move was particularly important after the Trump administration froze all meetings, travel, and communications from the National Institute of Health (NIH) and sent a directive to cut NIH funding of the University’s indirect research costs.

“We have to take a side on stuff when it comes to education and medicine, and we need to know how to have consensus amongst ourselves. Not everybody’s going to agree with everything, but I do think in certain circumstances, like abortion or withholding vaccinations, we need to come together,” Glick said.

Regarding the NIH’s cost cuts and the University’s lawsuit filed against the agency, Kalven highlighted one particular section of the Kalven Report that details the University’s responsibilities under exceptional circumstances that “threaten the very mission of the university and its values of free inquiry…. When people within the University—faculty, students, researchers—are subjected to that kind of attack, is their rigorous work transformed into a political issue that the University doesn’t address? Or does the University have an obligation to defend them?”

The Kalven Report states: “In such a crisis, it becomes the obligation of the university as an institution to oppose such measures and actively to defend its interests and its values.” The use of the word “obligation” is particularly significant here. “The president acknowledged an ‘obligation’ to resist the NIH cuts. I commend him for doing so,” Kalven said.

The present moment calls for a “return to the document and [to] really think hard about what its implications are,” he concluded. Glick, too, hoped the Kalven Report could be reevaluated and updated for the modern day. In the current political climate it seems dangerous to “keep our heads in the sand,” she said.