Over the last year, in response to national press reports on the University’s debt load and structural deficit, the University of Chicago’s leaders have held a sequence of “budget town halls.” In these, it has described the deficit in gross terms—it was $239 million in FY23, $288 million in FY24, and they project it to run to $221 million in FY25. They have never discussed the causes of the deficit beyond a very general admission that expenses grew faster than revenue. There has been no itemization of the capital investments that were funded by borrowing; no account of the distribution across units of endowment payouts from unrestricted funds; no study of the tradeoffs the University has made in order to direct billions in capital expenditures and vast additional operating expenses to the small number of areas selected for new and renewed investment; and no public discussion of the effects of spending choices on disfavored units. In consequence, there has been no study of our success along the different axes of endeavor that comprise the mission of a modern research university. Finally, there has been no consideration of the model of leadership under which the University has undertaken this project of transformation that I would characterize as entailing significant self-harm.

Given the extraordinary complexity of the modern university, I should spell out exactly what I mean in this context by “project of transformation.” In its 2009 strategic plan, the University of Chicago committed to invest substantial new funds in two areas of scientific inquiry, molecular engineering and astrophysics; to deepen the interpenetration between the University’s endeavors and those of Argonne National Laboratory, which the University manages for the Department of Energy; and to continue a program of expansion in the size of the undergraduate College. (The 2009 plan had many parts; these are the most salient in this context.) These programmatic changes in scientific endeavor had entailments that later urged further investment in related areas, especially computer science. Since then, new areas of inquiry have risen to importance that also call for major new spending, quantum computing and climate science foremost among these.

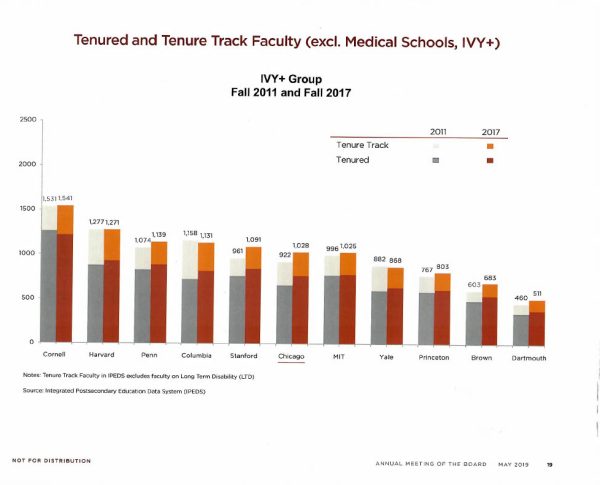

These changes were bold and intellectually unassailable as such. (One could, of course, contest on policy grounds, but that’s not an issue for this essay.) Unfortunately, they were not pursued with discipline. Spending spiraled out of control; the University’s debt grew and grew; and the University effectively abandoned an earlier ideal of itself as a graduate university in which undergraduates were taught by researchers in favor of a less aspirational, less expensive practice. In short, in an effort to drive down the amount it spends on classroom instruction, the University has cut and cut and cut the size of its doctoral programs; has allowed the faculty to student ratio over and over to deteriorate; and has met the increased demand for instruction of the contemporary College by hiring instructional rather than research faculty. In short, we exist today in a fundamentally different University than 20 years ago not simply because we do more things, but also because we are abandoning ideals of research and models of pedagogy that we long held dear. The University’s 2009 strategic plan regarded a then-recent decrease in its faculty-student ratio as a problem along two fronts, one related to the character of the institution and one related to faculty recruitment. On the one hand, the change “threatened our core ethos as a University that places a premium on rigorous inquiry.” On the other, “the shift in student to faculty ratio has reached a point where an important comparative advantage for us in recruiting faculty has been diminished” (p. 35). Values and self-interest converged to urge an increase in the size of the faculty. And yet, since 2011, the University’s leadership has constrained the hiring of research faculty in such a way that the University’s faculty-student ratio has become worse and worse. It was 5.83 in 2011, 6.13 in 2017, and 6.71 in 2023. (I draw the student numbers from the censuses of the University Registrar, historical faculty numbers from The University of Chicago. Data Trends—a booklet prepared for the meeting of the Board of Trustees in 2019 (figure 1)—, and current faculty numbers from data.uchicago.edu.) How are we to explain the University’s stunning divergence since 2011 from the official statement of its core ethos in 2009? Was there a process of academic deliberation through which we abandoned that ethos, or modified it, or redefined how we would actualize it? Or was this change a largely unreflective move in response to a self-created financial crisis?

On the surface, it thus appears that vast areas of University policy are being driven by financial exigency. It is of course also possible that these changes accord with the priorities of current leadership, which may dissent from the ideals of earlier years. Certainly, the University’s revenues have expanded enormously in recent years, so much so that the citation of financial constraint in any given context can appear pretextual. But either way, it is essential that members of the community come to grips with the University’s financial situation and the possibilities for improving it, for that is the context in which we will debate and act on our values.

In the budget town halls of December 7, 2023, and February 5, 2024, the University’s leaders laid out a plan to balance the budget through reducing expenses and raising revenue. They suggested that while a portion of the deficit would be addressed by targeted cuts, 50% of the deficit could be ameliorated through the combined revenue streams of technology transfer and increased enrollments in postgraduate degree and professional certification programs. The provost and chief financial officer have also issued the very sensible caveat that the temporalities of these processes differ: one can cut expenses faster than one can expand existing programs or develop new ones. Nevertheless, the existence of a plan, and disciplined adherence to it, are important. The provost averred in the latest budget town hall, on November 11, 2024, that an important reason that rating agencies had not downgraded the University’s bond rating is because of their faith in our “plan.”

In what follows, I present an assessment of the University’s plan along two fronts. First, I offer some cautions predicated on comparative data about the likelihood that the University can quickly generate revenue from either technology transfer or professional certification programs. Second, I review and critique prior budgetary projections offered by the University’s leadership to the Board of Trustees. Over more than a decade, these projections erred uniformly in their optimism. This, I suggest, was not an error of science but a feature of the system. Flattering their own prescience and boasting of their control does more than enhance our leaders’ own luster; by promising balanced budgets in the future, they free themselves to spend more in the present. In the world of contemporary academic leadership in which candidates jump from institution to institution, the inventors of shiny baubles move on, leaving financial wreckage and damaged institutions to the next generation.

The final section describes and discusses the model of leadership that got us into this mess and the specific damages being wreaked at the University of Chicago.

__________________

“Technology transfer” refers to the monetization of discoveries through university research by licensing them for development by private entities. This entire category of revenue is largely a modern creation. Before the Bayh-Dole act of 1980, patents given for discoveries made through publicly funded research were held by the People of the United States. In consequence, in 1979, on the eve of Bayh-Dole, 97 American universities received a total of only 264 patents. The Bayh-Dole act sought to direct the flow of research by encouraging the monetization of its results: it granted ownership of discoveries made in the course of federally funded research to non-profits (including universities) and certain categories of small businesses where that research was conducted. Nearly a quarter century later, in 2003, applications for patents by universities had increased to more than 7,500. In the same year, American universities struck some 4,500 licenses to private corporations to develop commercial applications for their discoveries (reviews of this history are available here, here, and here).

Can one count on making money by this means? The database of the Association of University Technology Managers suggests that in the early decades of Bayh-Dole, two thirds of the revenue tracked in its study went to a mere 13 institutions. Since then, the data have become harder to track because universities are so often investors in the firms to which their discoveries are licensed. Income no longer derives simply from licensing; and likewise, costs are harder to aggregate. As for the University of Chicago, I was told by an officer of the University in February 2024 that the University of Chicago has never received, in any year of its history, significant net revenue from its patents. And yet, the “plan” is to cover, in the near future, 25% of the structural deficit—perhaps $60 million per year—via technology transfer?

What about postgraduate degrees and professional certification programs? In the budget town halls, the provost and chief financial officer showed slides documenting the volume of enrollment at similar programs at peer institutions and the magnitude of tuition revenue that those institutions regularly earn. Comparative evidence from the world of on-line learning urges caution. In that “space” (to use the metaphor employed by the provost), the institutions that dominated enrollment and earnings in its early days—Southern New Hampshire University, Georgia Tech, and Arizona State prominent among these—have maintained their dominance, despite the efforts of more highly-ranked institutions to break in. Do we imagine that the market for professional certification is suddenly going to expand and that a significant percentage of those customers will flock to the new kid on the block, rather than the established players? Certainly, the history of on-line learning suggests that Harvard, which currently dominates the “space” of professional certification, is not going simply to yield market share to us, whether from inattention or generosity. Gold does not lie at the end of this rainbow.

There is also a very good reason, specific to the University of Chicago, to be skeptical of the “plan’s” reliance in professional certification programs. In an earlier period of handwringing about the budget, which stretched from 2016 into 2017 and included a liquidity crisis that led to a fire sale of University properties, the University’s leadership also announced a plan to increase revenue, based on—wait for it—increased enrollment in postgraduate degree and professional certification programs. This history deserves some scrutiny.

The briefings provided by the president to the trustees, and by the provost to the trustees’ “Financial Planning Committee,” routinely present projections of revenue and expenditures, as regards both specific endeavors and the University as a whole. Here, I set aside projections about specific projects, lest I seem to cast aspersion on the academic worth of any given endeavor. But even in regard to the budget as a whole, in the documentation available to me, the projections offered by the University’s leadership have consistently been wildly optimistic.

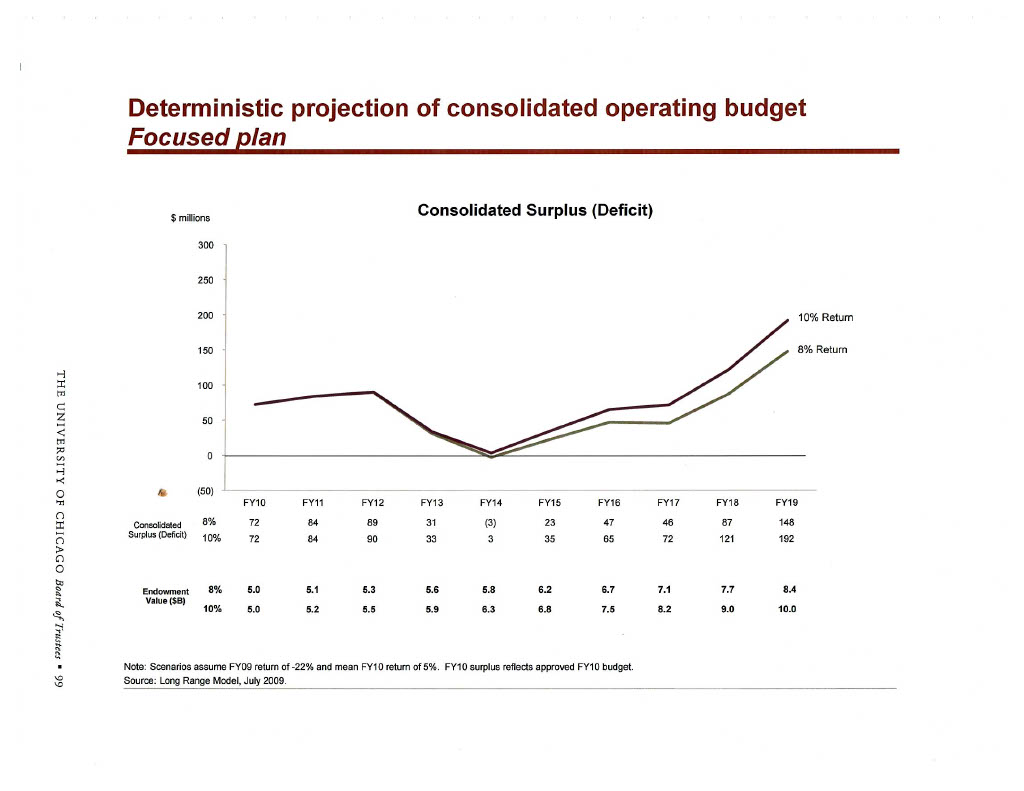

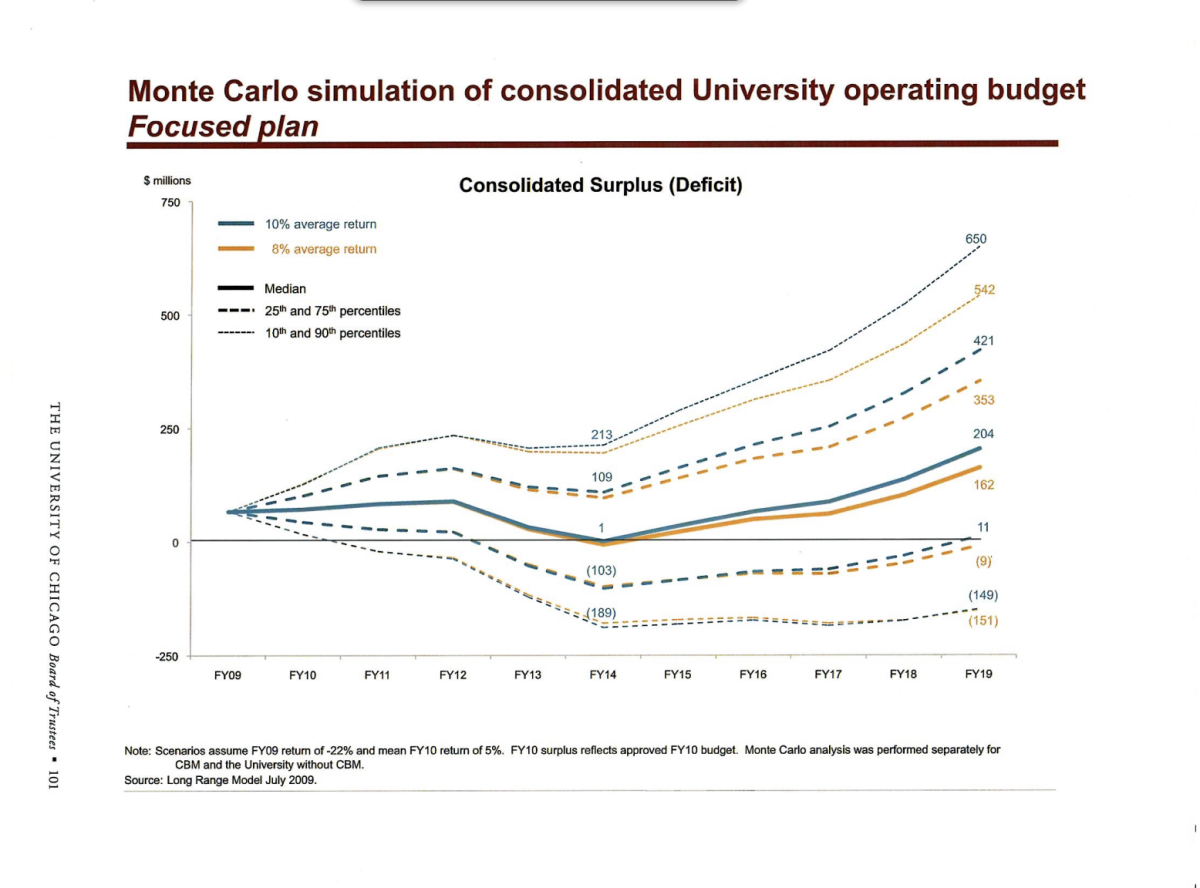

In 2009, for example, in a 302-page strategic plan entitled Moving Forward. The University’s Strategic Approach to Risks and Opportunities, presented to the trustees in September in Washington, D.C., the University of Chicago’s leadership presented both a deterministic projection and a Monte Carlo simulation of the operating budget. It used each method for two scenarios: one holding commitments steady, and the other if the trustees approved leadership’s plan for investment in new areas. Its deterministic projection had the University running an operating surplus from 2010 through 2019, with only one year at balance (figure 2); its Monte Carlo simulation allowed for the possibility of deficits under certain variables, but its median projection under conditions of lower endowment returns nevertheless displayed surpluses nearly every year (figure 3).

In the same document, the University’s leadership evaluated the impact of borrowing between $600 million and $1 billion between 2009 and 2014, “to continue to fund strategic capital plans.” It allowed that, at the higher level of borrowing, “it appears more likely that we will have a rating downgrade.” Therefore, “to move forward with new borrowing, we need to show balanced operations and sustained net operating cash surplus positions” (p. 161). In 2009, the University’s “notes and bonds payable” amounted to $2.415 billion. In 2014, that number was $3.700 billion. Why did we borrow so much more than the worst-case scenario? A partial explanation, at least, can be gleaned from the University’s public financial statements. Over the five-year period from 2009-2014, the University never showed “balanced operations” and never achieved a “net operating surplus cash position.” “Net cash used in operating activities” was negative every single year. In total over that period, operating activities “used” $390 million more in cash than they “provided.” (The terms are those of the financial statements.)

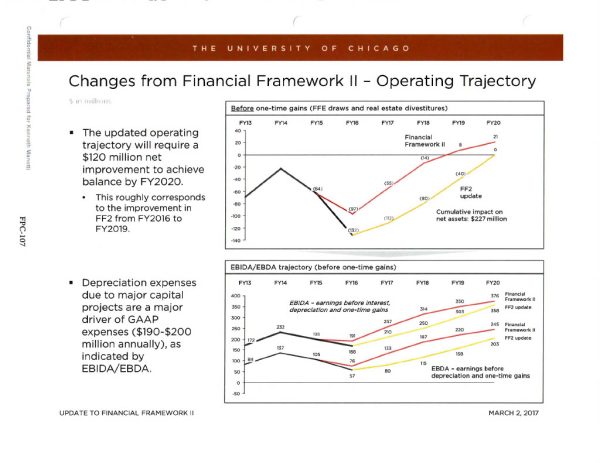

Having borrowed $300 million more than its own highest (worst?) projection from 2009, the University’s leadership presented the trustees with a series of “Financial Frameworks,” outlining efforts at “Cost Containment, “Administrative Transformation,” “Strategic Sourcing,” and the like. In 2016, the provost told the trustees’ Financial Planning Committee that these efforts would result in $419 million dollars in savings over five years, which would free up funds “to support strategic investments and create a path to balanced budgets.” (The combination of capital letters and precise numbers was presumably intended to convey seriousness and rigor.) By 2017—one year later!—”Financial Framework II” already required updating. As the chart outlining the revision makes clear (figure 4), the University had never achieved the balanced budgets, to say nothing of the surpluses, envisioned in 2009. Nor would we achieve the budget surplus of $21 million envisioned in “Financial Framework II.” Instead, “FF2 update,” as it was called, promised a balanced budget by FY20.

In FY20, the University of Chicago ran a deficit of $185 million.

When I say that the budget projections of the University’s leadership have consistently been “optimistic,” I refer not to an affective relation to the future, but to leadership’s claims about its own prescience and skill. The principal effect of this self-aggrandizing behavior has been to persuade persons and institutions in different relations of oversight to the University—both the trustees and ratings agencies—that the leadership should be free to spend more, because it has things under control. It has a plan.

__________________

This brief assessment of the University’s current plan, and review of its earlier plans, raises questions of two kinds, concerning the model of leadership that over twenty years created this mess and concerning the specific situation of the University of Chicago today. I take these in turn.

In recent years, when the need was felt to justify the extraordinary pay packages given to university leaders, it was common to compare the size and complexity of universities to those of for-profit corporations. The University of Chicago is unquestionably a multi-billion-dollar corporation. But the relationship of its leaders to the health of the enterprise is fundamentally different from that of officers of for-profit companies to their enterprises. Persons paid partially in shares that they are required to hold are, at least in theory, incentivized to pursue the long-term health of the entity as measured by the price of its stock. No similar incentive, nor any similar constraint, exists for leaders of universities. On the contrary, leaders of universities—particularly young persons in leadership roles—are strongly incentivized to pursue legible forms of “growth” and “innovation,” the better to burnish their resumé for the next job. For this, money is required. At the University of Chicago, for a long time this money was found on the bond market; of late, we are bleeding nearly all parts of the University to pay for others.

Perversely, despite the absence of contractual guardrails on the conduct of leadership, leaders of universities differ from their corporate brethren in another significant way. They do their business in secret. When Ford Motor Company decides to shift production toward electric vehicles or, indeed, back to internal combustion engines, it announces this decision to shareholders; the ramifications of this for the operation or viability of particular plants and subsidiaries is openly discussed; and so on. Large-scale decisions about priorities at private universities and, indeed, at many public ones, are often made out of sight and never announced. It is a matter of the deepest irony that contemporary universities so uniformly subscribe to a model of leadership in which power is concentrated and information withheld.

The briefing books of the University of Chicago’s Board of Trustees reveal that the trustees are occasionally informed when leadership believes cuts to the budget in one or another area will harm institutional operations and diminish excellence. But far more regularly they have been told that, on this occasion, a rabbit will actually be pulled from a hat or, rather, the very rabbit that one has always been promised will finally be pulled from the very same hat from which we have failed to pull one in the past: efficiencies will be wrung from the further concentration of “services”; despite a decade of failure, this time we really will enroll more fee-paying students in certification education. The ongoing credulity of the trustees is hard to explain except as an astonishing failure of judgment.

But perhaps we are mistaken in assuming a set of shared values between faculty and leadership, and likewise, perhaps we err in attributing mere credulity to the trustees. If, instead of positing that the University’s leaders actually believe their plan, one were to examine what is in fact happening at the University, a very different plan comes into view. For a decade or more, but in an accelerating way under current leadership, the health of a huge number of departments and programs at the University is being starved. More and more instruction is being delivered by staff who are not assessed on the basis of their contributions to knowledge; the number of faculty is decreasing in proportion to the student body. We decline to be fully ADA compliant; we renege occasionally on our commitment to need-blind admissions; we pay women worse than men; the library has become at best second-rate. We are slowly but deliberately abandoning a core ethos of the University: that teaching in a context of “rigorous inquiry”—teaching students to become critics and creators of knowledge—requires that instruction be delivered by persons engaged in research.

As I have pointed out elsewhere, all this is occurring while the University makes more and more money, in part because it continues to increase tuition for the very students it shortchanges. So far as I can tell, this is because the current leadership of the University—including the trustees—have a very different conception of the purpose of the University. As children of Bayh-Dole, they think of the University fundamentally as a tax-free technology incubator—an engine, as it were, for private wealth creation. Of course, it can only maintain its tax-free status by teaching students, but nothing requires that we do this as well as possible or that monies raised from tuition be spent on education.

Mine is a partisan view, in the sense that it is informed by a deeply held but nevertheless personal view of the ideals of the research University. But there can be no doubt that a great institution, with a deep call upon our affections, is being transformed. At the same time, the wider foundation of the health of higher education as a whole, in the form of public opinion and legislative support, is clearly in flux (for Gallup’s report on its annual survey see here; for an analysis by the AAU, see here). I exhort all those who care about future of the University of Chicago to study the situation, form an opinion, and speak up.

Clifford Ando is the Robert O. Anderson Distinguished Service Professor in the Departments of Classics and History and in the College, as well as Extraordinary Professor in the Department of Ancient Studies at Stellenbosch University.

Be quiet! / Jan 16, 2025 at 8:11 am

Once again, we are treated to yet another verbose diatribe from the so-called Distinguished Service Professor, who seems more committed to defending the bloated carcass of academic irrelevance than confronting the stark reality of modern education. Clifford Ando’s latest lament is little more than a glorified eulogy for the University’s waning commitment to his beloved echo chambers of liberal arts, all while studiously ignoring the University’s obligation to evolve in a world that demands innovation and pragmatism.

Let us address the core of his grievance: the alleged “self-harm” of the University’s transformation. This narrative conveniently ignores the obvious—that the University’s investments in fields like quantum computing, climate science, and molecular engineering are not mere indulgences but necessary recalibrations for an institution that seeks relevance in the 21st century. Ando’s obsession with faculty-student ratios and “rigorous inquiry” is nothing more than an academic dog whistle for preserving his own enclave of unproductive scholarship, where tenured faculty churn out esoteric papers no one reads while contributing little to the broader mission of societal progress.

His lament about technology transfer as a “modern creation” betrays a stunning lack of understanding about how universities must function in a world where public funding is dwindling, and private innovation is king. The Bayh-Dole Act wasn’t some neoliberal conspiracy; it was a lifeline to ensure that research didn’t gather dust in ivory towers but translated into tangible advancements. And yet, Ando casts it as a villain, as though the University should return to the days when academic discoveries were nothing more than intellectual curiosities locked away in library stacks. Perhaps he yearns for a time when his department could gorge itself on unrestricted funds without accountability, producing nothing but self-congratulation disguised as scholarship.

But the true centerpiece of this screed is Ando’s thinly veiled contempt for professional certification programs and revenue-generating initiatives. He derides these efforts as beneath the dignity of the University, as though expanding access to education and generating revenue for critical investments are somehow antithetical to academic excellence. This is the same elitist nonsense that has long plagued institutions like UChicago, where the humanities faculty cling to an outdated vision of academia as a sacred temple, untouched by the dirty realities of economics.

Ando’s critique of the University’s leadership is equally laughable. He accuses them of “self-aggrandizing behavior,” but let’s be honest: it takes far more courage to restructure an institution in the face of financial and societal pressures than it does to pen yet another op-ed decrying the loss of some imagined golden age. His complaint that the University is becoming a “tax-free technology incubator” would almost be amusing if it weren’t so delusional. Does he seriously believe that the path to institutional salvation lies in doubling down on departments that contribute little to the University’s reputation, let alone its financial health?

And let’s not forget the obligatory invocation of D.E.I. and performative activism—although in Ando’s case, it’s more of a subtext than a headline. It’s no secret that departments like his have leaned heavily into these initiatives, redirecting resources away from meaningful academic work and toward ideological navel-gazing. If Ando truly cared about the financial health of the University, he’d turn his ire toward the humanities’ penchant for hiring redundant faculty whose primary contribution is shouting into the void of social justice Twitter.

Here’s the hard truth: the humanities are no longer the intellectual backbone of the University. They are a luxury, and like all luxuries, they must justify their existence. If the trustees and leadership are prioritizing fields with real-world impact, it’s not a betrayal—it’s survival. The days of unlimited funding for departments that produce little more than intellectual vanity projects are over. And if that means fewer resources for Ando and his colleagues to bemoan their declining influence in verbose, unnecessarily long essays, so be it.

In the end, Ando’s piece isn’t a call to action—it’s a tantrum. A desperate plea to restore the primacy of a dying worldview, wrapped in the language of concern for the University’s future. But make no mistake: his vision is not one of progress, but of stagnation. And as the University charts its course into the future, it would do well to leave voices like his firmly in the past.

Stop whining. / Jan 13, 2025 at 4:04 pm

It is unfortunate that this screed was allowed to be published. Beyond being so poorly written and researched to the point of being incomprehensible, it is redundant and moronic.

Yet again the Maroon’s editors were forced to bend over backwards to accommodate Ando’s poorly written work! Screeching into the ether, tarnishing the university’s reputation (yet again) instead of taking up his grievances through an appropriate channel.

Ando is a serial complainer who, evidently, has far too much time on his hands. The embodiment of the university’s bureaucratic bloat.

be quiet / Jan 12, 2025 at 6:56 pm

OMG shut up already

Anonymous / Jan 10, 2025 at 11:32 am

Ando’s analysis of the state of the university’s finances has been very illuminating, and is clearly worthy of praise. But his remarks about his non-tenure-track colleagues have been consistently embarrassing. To say that instructional faculty are not researchers is wildly misleading. To be sure, they are not paid for their research or supported in their research, but a great many of them continue to produce peer-reviewed research in their own time nonetheless. Nor does Ando seem to have the slightest insight into the sector-wide shift from TT to NTT hiring over the last 17 years or so. But to give the impression that the increased turn to instructional faculty is doing a disservice to our students is an outrageous assertion, offered without any shred of evidence.

Ando is right to think we should fight for a better vision of the university, and that this should begin with a return to more robust faculty governance. But he would do well to consider that this is unlikely to result from the kind of excessive self-regard that leads one—wittingly or otherwise—to indulge in a practice of denigrating one’s colleagues and dividing the faculty against itself.

Matthew G. Andersson, '96, Booth MBA / Jan 9, 2025 at 10:25 pm

Pathology may not be quite the right diagnosis, unless administrative rationalization or denial are so (as in the C19 project). Difficulties in forecasting otherwise usually stem from revenue, versus cost projections. Cost reduction requires no per se forecast, only implementation, as it is under managerial control. Revenue is not, and capital is subject to entrepreneurship. Chicago is somewhat vulnerable to aggressive pro forma revenue, and strategic program error, because it is not appropriately funded at the endowment level, versus Yale, Harvard and Texas, for example. That it weights science and engineering is rational, but revenue realized from such allocations always lags cost. Otherwise, everything that a university does, can be done in half the time, for half the cost, at twice the efficiency and quality. Until that strategic goal is set and realized, the corporation, like all corporations, will remain unstable, and underperforming, regardless of revenue which is always subject to adjustment.

Anonymous Andy / Jan 9, 2025 at 3:15 pm

I appreciate how Professor Ando acknowledges that universities—at least, nowadays—operate similar to for-profit corporations. He observes an issue behind this way of running a university I have never considered: the limited constraints on leadership.

As Professor Ando points out, corporate executives are beholden to their shareholders and must keep them informed. What stops members of university leadership from making bad business decisions? Having to put down fewer crowning achievements on their already stellar resumes? This is a powerful insight.

Michael Kremer, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy / Jan 9, 2025 at 11:44 am

Excellent and crucial analysis. This should be widely read.