In North Lawndale, Theatre Y’s production of Richard Maxwell’s 2006 play The End of Reality is not for the faint of body, mind, or heart, and not for those uninterested in meta-theatrics. The play, commonly regarded as Maxwell’s best and most complete work, depicts a world of alternating boredom and violence. Security guards Tom, Brian, Jake, Shannon, and Marcia guard an unknown building, and their conversations and pontifications are occasionally interrupted by the appearance of the man “3,” who will beat one of them bloody and then leave.

The End of Reality owes much to the hugely influential absurdist theater-makers of the late 20th century, including Harold Pinter and Samuel Beckett. But it is of this time, and wonderfully so. Its sudden violence is filled not with terror and dread, as is the violence in Pinter’s The Birthday Party, but with acquiescence and hopelessness. And its characters are not so existentially minded as those in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, but rather are forlorn, not expecting anyone or anything to save them. There is certainly something of the absurdists’ love of pauses, of language that says much and means little and vice versa, and of the stripping away of theatrical excess. However, The End of Reality brings a 21st-century listlessness to a by now well-explored plot: a visitor comes or doesn’t come and takes or doesn’t take someone away.

Maxwell’s dialogue is filled with funny quips, played dryly; rambling philosophy, played dryly; and questions about coworkers’ personal lives, played with only slightly more warmth. This is an exceedingly difficult script with which to work, stretched over two uninterrupted hours, and, for the most part, this cast does well. In particular, Matt Fleming as Tom and Willie Round as Brian excel. In his smooth cadence, Fleming brings great depth of emotion to a man who shows none of that emotion outwardly. Brian similarly manages to portray great sadness through his continued shows of strength. These are wounded, human men, but they are just as much studies in masculinity.

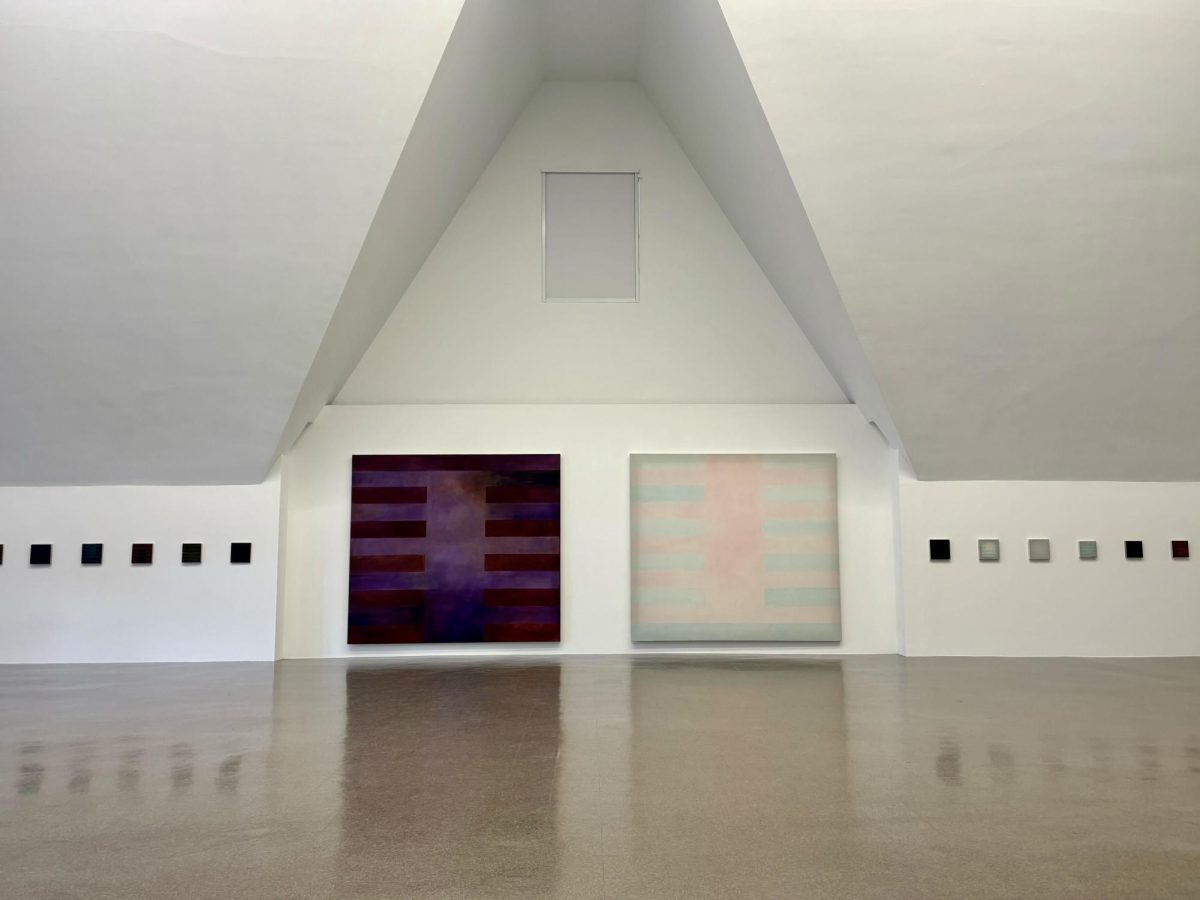

Tom, sprinting mesmerizingly around, and Brian, punching again and again into the air, seem mere specks in a massive warehouse space. There is a promenade; there is a thrust; there is a theater-in-the-round—but these terms lose meaning. The audience is assembled in two lines of little chairs, facing each other, and all around and between them actors scurry, scream, and (most commonly) stare blankly into space. This is a play about silence and stillness as much as it is about sound and fury, and Director Melissa Lorraine finds a strong balance between those qualities. The meaning, if there is much in The End of Reality, is not clear to the characters, so neither should it be clear to the audience. There is great intentionality to the security guards’ many tasks, but explanation is infrequently supplied.

In its pleasing confusion, Kimberly Sutton’s sound design also delights. There’s a bit of everything, from ’60s rock and roll to Queen Latifah to an absurd amount of jazzy elevator music and even some Rocky-esque pump-up melodies. Part of 21st-century theater’s great joy has been in mixing genres. Here, alongside the myriad of music, there are moments of romance, drama, melodrama, horror, mystery, and tragedy. There are also air raid sirens, crowd noises, and the thuds of fists to faces. Every few minutes, a freight train rumbles past just outside the warehouse’s sheet metal doors, completing The End of Reality’s atmosphere. The audience, like it or not, is stuck in this world, with all its monotony, uncertainty, and sudden sounds.

To judge a production like this one on aesthetics is essentially pointless; Maxwell is, in this play, throwing modernism and postmodernism, as well as character, plot, and beauty, to the curb. However, there is, in all its reduction of the human condition, almost something naturalistic about this work. What I would say, then, is threefold. First, this is not theater in the traditional sense, and it is not for those who seek meaning rather than experience. Second, even for those accustomed to absurdist theater, The End of Reality can prove difficult to grapple with. Its tangents are often genuinely random: at one point Marcia bemoans liberalism; at another Tom’s body is made to represent the crucified Christ. Additionally, much of the dialogue in The End of Reality is delivered in the slow, flat monotone for which Maxwell has become somewhat famous.

But third, this is theater as much as anything is theater. This is event. This is drama in a fleeting moment. In their total rejection of the beauty that often accompanies depictions of violence and hopelessness in the arts, Maxwell and Theatre Y have conjured something vivid and dynamic.

Richard Maxwell’s The End of Reality is playing at Theatre Y through June 15.