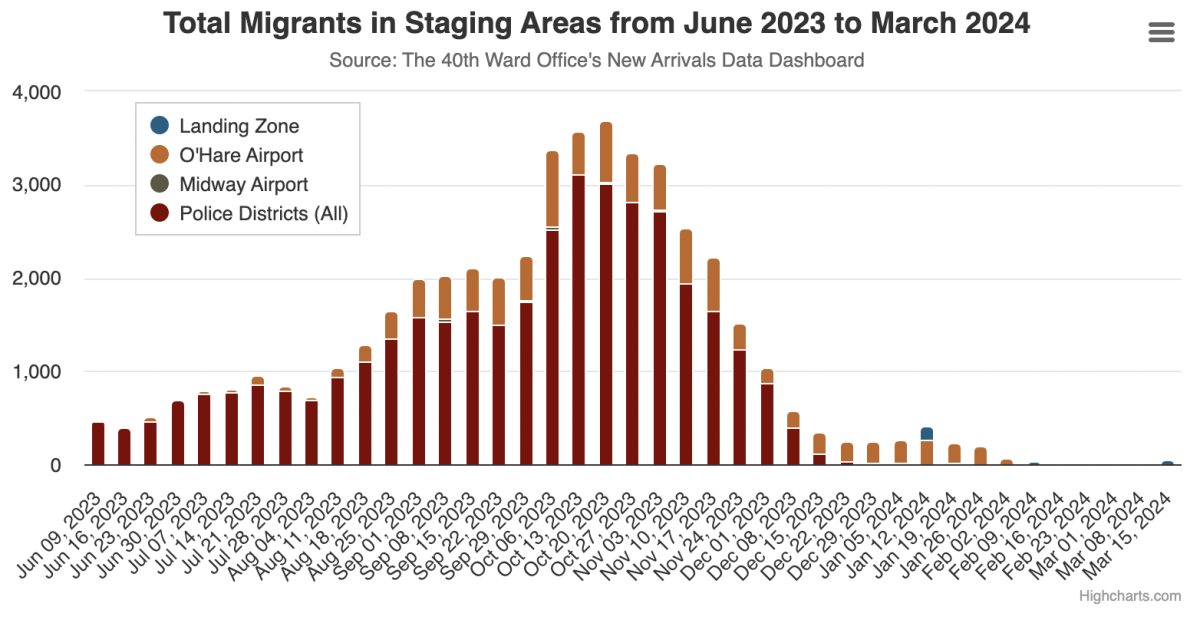

Working in an emergency room in the South Side is filled with its unique challenges, and ever since Chicago started to receive an influx of migrants coming from the Southern US border in August 2022, Dr. Abdullah Pratt found himself rethinking his role in the hospital and beyond.

Pratt grew up in the South Side and has an intimate understanding of the problems that afflict the area, especially its Black communities. With the recent introduction of migrants, which has sparked tension and dissatisfaction over the way in which the city’s leadership has decided to allocate resources, Pratt has taken on a dual role. He is both a medical professional caring for the community members’ physical health, but also a community leader rallying for the UChicago community to come together to support the South Side’s new residents.

Pratt wears many hats: he is an emergency medicine physician at the UChicago Medical and Trauma Center, Faculty Director of Community Engagement for the Pritzker School of Medicine; he is the founder of the nonprofit Medical Careers Exposure and Emergency Preparedness (MedCEEP) initiative and the Trauma Recovery and Prevention of Violence Program (TRAP Violence); he is also a resident dean for Snell-Hitchcock Hall.

“Historically, the South Side patient population is mostly African American, and we have Latinx patients as well. We’re working with an overburdened healthcare system, patients who’re usually of lower socioeconomic status, who have lower levels of health literacy, and populations that have a lower ability to produce medical professionals,” Pratt said of the structural challenges that he is already used to dealing with, but the new arrivals have revealed new weaknesses within the system.

The migrants do not have healthcare insurance or doctors among them. On top of that, Pratt has found that language barriers and limited knowledge of the American healthcare system and their own medical histories has made it challenging for migrants to access timely medical help. “The migrants who come to us are often much more sick. For example, when sepsis isn’t treated immediately, it worsens from just being a localized infection to becoming blood-borne, which is when it becomes life-threatening. Also, we have no knowledge of their medical history…so we’re receiving mothers and children with symptoms, pregnant women who don’t know their dates, patients who don’t know their infection history,” Pratt said.

These barriers to healthcare create frustration and unhappiness for both the staff and the patients. “[The patients] are frustrated. They ask us questions like ‘why am I waiting for so long’ because they’ve been sent around in circles,” Pratt said. “Communication is difficult sometimes because we have to remember that these people are also coming with lots of trauma—some are victims of assault, fights, domestic violence, or gun violence.”

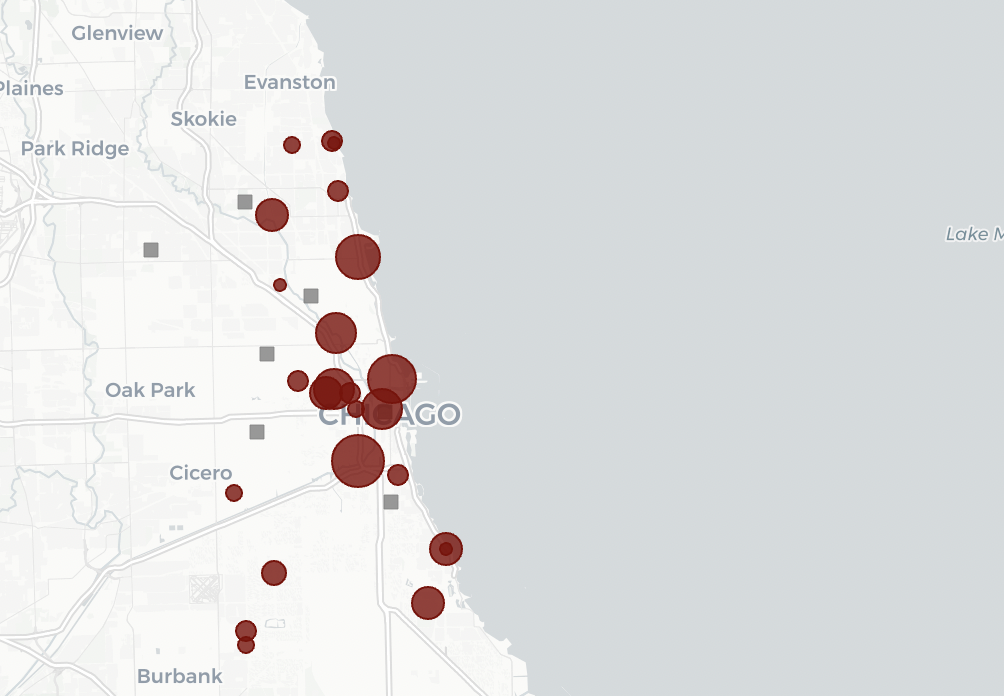

Pratt also observed that there have been rising tensions within the South Side community ever since the migrants arrived. “There’s anger that resources are being directed to migrants. They’ve fixed up schools to host migrants, when the locals have been asking for years to get those schools fixed so the neighborhood can have more schools for their kids,” he said. One example of these tensions is Wadsworth Elementary school in Woodlawn, which was converted to a migrant shelter in February, 2023. The Hyde Park Herald reported that a physical altercation had broken out on July 14, 2023 when a resident found her driveway blocked by some shelter residents. This is but one example revealing the pent-up frustration that residents of historically underinvested neighborhoods hold toward the incoming migrants.

As a doctor, Pratt is constantly working to understand how to solve long-standing health disparities, what it truly means to treat every patient humanely, and what can be done to bring communities together to collaborate instead of compete. “As someone who’s already deeply involved with this community, the question that I ask myself is, what can we do as shepherds [to address these tensions] because we have to remember that, ultimately, [the migrants] are here for their own humanity.”

Respecting each individual’s humanity has become a cornerstone of Pratt’s advocacy. “The migrants are human. Treating them like humans is different from what we Americans think,” he said. “It’s about empathy, not sympathy.”

He recalled one patient in particular who inspired him. “One day we had a patient come in; he was a Spanish-speaking middle-aged man with very bad knee pain. The nurse came and told me that he was threatening the staff—he swung and tried to punch a nurse. The nurse who was translating said that he said, ‘My knee hurts a lot, I deserve to be treated like a human too.’ After I treated him, he apologized for his actions. He said that he was in so much pain that he couldn’t think straight,” Pratt said.

The interaction revealed for Pratt how migrants are often subject to dehumanizing portrayals and treatments that prevent them from being afforded the dignity and care that they deserve. Such narratives promoting ideas that migrants are “stealing jobs” or are content to work labor-intensive jobs while being paid below minimum wage are harmful for both migrants and locals, and deconstructing them, to Pratt, is the first step to mitigating tension.

“Some migrants are disillusioned by how they still can’t make enough money despite getting housing and stipends. This dispels the myths that the Black community is poor because they’re lazy, that migrants are ‘stealing jobs,’” Pratt said. To him, the migrants’ disillusionment highlighted how there were structural reasons preventing underprivileged groups from making a living wage even if they had some support in the form of stipends. “These narratives [of laziness and job stealing] are harmful to all communities: it’s not true that migrants are willing to work for unlivable wages, it makes the assumption that migrants are made to work and work and it’s okay for them to be treated as less human,” he said.

Pratt therefore believes that helping the migrants will be beneficial to the local community on top of being a moral responsibility. “The least that we can do is give them some help since they’re part of the community already,” he said. He tries to organize efforts that involve partnerships between different communities so as to enhance mutual understanding and create more equitable solutions. “To me, equity is achieved when a problem is met with an equal or greater solution,” Pratt said. “So communities that are in greater need should get more help.”

One such partnership was created by Pratt when he organized “Thanksgiving for the Migrants” on November 17, 2023. This initiative involved migrant community leaders like Dr. Alfredo Lopez, other nonprofits, students from the Pritzker Medical School, and even students from Snell-Hitchcock Hall. Lopez is the chief scribe of the UC Med Adult Emergency Department (ED), and Pratt entrusted him with the leadership of the event.

“Alfredo had approached me before to ask how he could help, and he’s someone who understands the migrant community. He left Venezuela when he was 17 and managed to get visa status, so I told him, ‘I want you to lead this effort.’ I wanted to build him up as a community leader and [support him to create] more doctors from that community,” he said. “He’s now a national leader and involved in efforts like this everywhere.”

Lopez suggested that they distribute arepas, which are a staple in Venezuela and Colombia. Pratt opened Snell-Hitchcock’s main kitchen and invited students from Snell-Hitchcock to come and help make the arepas because “we need to give kids the opportunity to give back to the community [and] learn about other cultures,” Pratt said. Other nonprofits helped with the food distribution, in addition to bringing other necessities like coats, socks, and blankets. The Latino Medical Student Association from the UChicago Pritzker School of Medicine also volunteered at the event.

Keeping morale up is challenging since doctors like Pratt are already extremely busy handling their responsibilities in the ED and elsewhere. The influx of migrants has also meant longer working hours because of the rise in patient volume. “There’s definitely an increased burden [in the ED that] deters people who want to help but can’t because they need to prioritize supporting their families, but it’s a double-edged sword. [Helping migrants] helps us cope with the problems of our system. Some of us share an affinity with their plight because we grew up helpless to things like diabetes, sickle cell disease that affected people around us. [It also feels like] we’re living up to the image that our younger selves had,” Pratt said.

Notably, Pratt did not always have emergency medicine as his dream career in mind. When he first started out in medical school, he had wanted to specialize in sports medicine. In 2012, however, an especially intense level of community violence led to the murders of many of his loved ones, his older brother among them. This was the pivotal moment that led Pratt to change his career goal: “My number one concern became the community,” he said. “As an ER doctor, I have more leverage to address issues like gun violence and maternal fatality, and a better platform to advocate for change.”

He took a gap year for therapy and did research with Dr. Monica Peek, who is an advocate for reducing healthcare disparities. The experience inspired him to advocate for creating a Level I trauma center for the South Side, which has historically lagged behind in terms of healthcare access. “Before UChicago Medicine was founded in 1899, patients here didn’t even have a hospital and needed to go up North,” he said. “I worked with the other community groups that were protesting, and the Medicine School and Hospital leadership were graceful enough to teach me about the dynamics [of pushing for change from within the system].”

The trauma center was initially viewed as an unprofitable and unnecessary venture that placed additional burdens on patient care, but it proved to be good for the hospital as well as the community in the end. “The trauma center has actually helped us to make money, especially thanks to the Affordable Care Act under the Obama administration,” Pratt said.

During his medical school years, Pratt also founded the nonprofit Medical Careers Exposure and Emergency Preparedness (MedCEEP) that seeks to build up emergency preparedness and next generation medical professionals like emergency medical technicians in underrepresented groups. Pratt led workshops training youth and adults in skills like cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and treating gunshot wounds. These workshops then uncovered another need within the community: trauma recovery. “It was difficult to finish the workshops sometimes because the children and youth would be sharing their trauma. Many of them have experienced traumatic events—some of them have seen their friends get shot,” Pratt said.

Consequently, the Trauma Recovery and Prevention of Violence Program (TRAP Violence) was founded as part of MedCEEP, which focused on youth violence prevention and helping youth overcome depression. “We borrowed from resources for violence recovering programs for adults and made them suitable for youth, and we [were also informed by] sources like the National Institute of Health’s studies on youth violence prevention programs,” Pratt said. “The best strategy to prevent trauma is to reduce the number of people being shot [through violence prevention programs] and let the healthcare system prevent the worst-case scenarios from happening.”

Mentoring the youth became a key part of Pratt’s work after he realized the positive impacts that initiatives like MedCEEP had on their lives. “We have kids from our high school programs who now want jobs here [at UCMed]! You can see the product of uplifting them,” Pratt said. “As a mentor, [the most important thing is] do not get discouraged. Change the small things—no one has to be a big superhero. Make sure that your efforts can be modeled and spread.”

Ultimately, bridging the gap between these different groups—the communities that he helps, the youth, and other advocacy groups—is paramount to Pratt, who firmly believes that “the people shouldn’t be fighting. We must hold policy makers accountable to prevent further violence.”

Patricia Putman Barlow M.D. / Mar 31, 2025 at 6:09 pm

Dr. Pratt…this question does not relate to migrant care. It relates to YOU. In a community that produced you, but also produces children who grow up to join gangs…killing one another. What were the factors that created you…an amazing and remarkable human being? Whatever those factors were, we need them to be provided to every child in America. THAT is what we need to focus on. The other factors are just a massive waste of time and money.