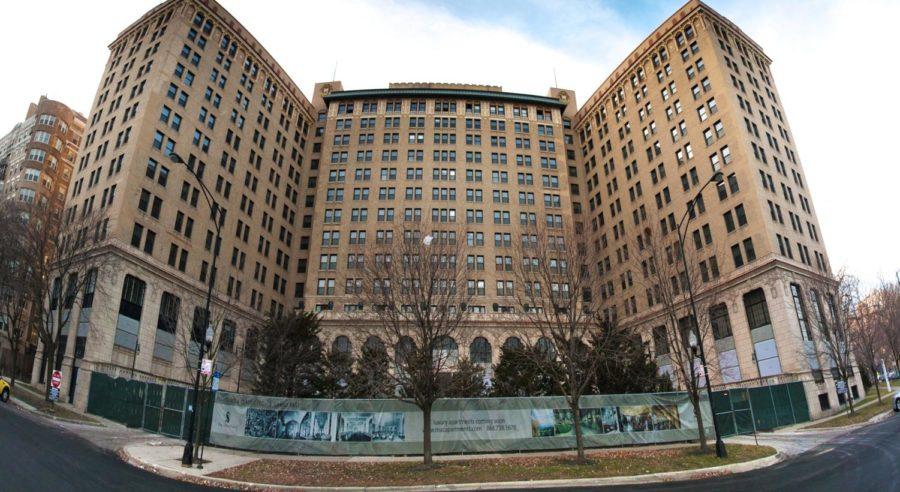

Formerly a campus landmark and a thriving dormitory, the Shoreland now stands vacant on the coast of Lake Michigan, as if washed up.

The seemingly abandoned property is strewn with old building permits from previous years, with advertising on the fencing promising luxury apartments and a return of the complex to its former glory. A sign reads: “Restoring a Classic from a Grand Past to a Luxurious Future.” Dumpsters inside the fencing are filled with the refuse of interior demolition, the only indicators of renovation on the site.

Those unfamiliar with the Shoreland, formerly Shoreland Hall of the University housing system, might see it only as another lakeside high-rise. Having cut ties with the property in 2004—and preparing to bid farewell this spring to the last class of Maroons to have lived there—the University no longer bears its mark on the 1920s relic.

Now in its fourth year of development under Antheus Capital, parent company of MAC Property Management, the Shoreland’s revival is tentative: A representative from the MAC office on East 53rd Street could only say that it would be “at least two years” before the Shoreland opens its doors again.

Built in 1926 as a hotel, the Shoreland once was among the poshest haunts in all of Chicago. Frequented by politicians, movie stars, and bootleggers, the Shoreland attracted the likes of Al Capone, Elvis Presley, and Jimmy Hoffa.

However, financial difficulties led to the building’s foreclosure in the 1970’s, at which point the University swept in and bought it for $750,000.

Over the next three decades, thousands of students and faculty would call the Shoreland home. At the height of its use as a dormitory, the building had an occupancy of 600. Though over a mile from campus and the quads, the dormitory was beloved for its large rooms, personal bathrooms and kitchens, scenic views of the lake and downtown, and the charm of a Jazz Age hotel.

However, some were quick to note the deteriorating physical condition of the building. Speaking to the Maroon in 2006, former Shoreland Resident Master Lawrence Rothfield said that the building “looks like the set of A Nightmare Before Christmas.” Toward the end of its University days, the building suffered from broken elevators, crumbling plaster, and general maintenance concerns.

The final straw was a series of changes to the Chicago building code in 1999, which led the University to begin seeking a buyer for the property; in 2001, a facilities audit of the site found that nearly $50 million in renovations would be needed to bring the Shoreland up to code.

The University sold the building for $5.7 million in 2004 to Kenard Developers, who laid out initial plans for 260 residential units and a six-story parking garage but sold the building two years later to R.D. Horner and Associates for $10 million. Horner permitted the University to continue leasing the building for dormitory space and planned to open up the Shoreland for residential use in 2009. In 2008, however, Antheus bought the building for a reported $16 million, nearly three times what Kenard purchased the Shoreland for just four years earlier.

Today, Antheus holds the deed to the Shoreland, and MAC manages the development of the property. The building permit for interior demolition is underwritten by an limited liability company in Englewood, NJ, also the location of Antheus’s headquarters.

Recently, concerns over parking, the building’s historic architecture, and its significance to the Hyde Park community have dogged plans for the Shoreland and stymied more aggressive development. The city and neighborhood have extensively reviewed building plans, eyeing the availability of parking spaces and the flow of traffic off Lake Shore Drive.

The U of C no longer has any formal relationship with the Shoreland, according to University spokesperson Steven Kloehn; ties were officially cut with the building upon the opening of the South Campus Residence Hall in 2009.

Once the current fourth-years who lived in the Shoreland three years ago graduate, the Shoreland will disappear from campus memory. Many younger students don’t know of the student murals in the hallways or the mile-long walks to campus in the rough of the Chicago winter, the drunken painting parties or the camaraderie the Shoreland engendered in its hundreds of student residents.

Until MAC finishes construction and opens the doors of the Shoreland to a new generation of inhabitants, the building stands as a monolithic reminder of the University’s history and the changing dynamic of Hyde Park.