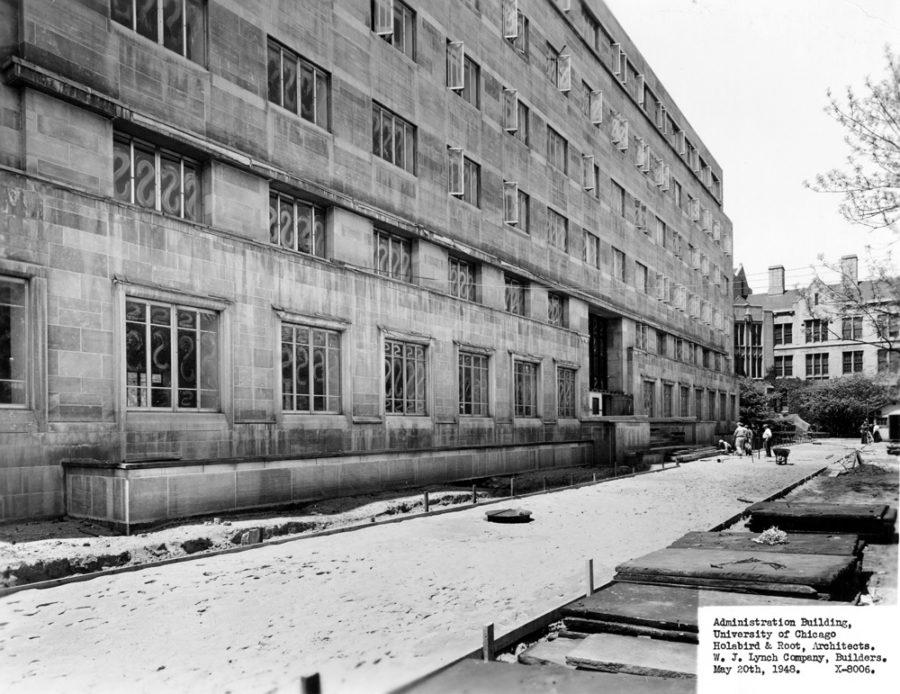

UChicago has a long history of graduate workshops, which aim to bring students from different disciplines together in order to facilitate intellectual exchange. This autumn, the U.S. History Workshop has a new policy, affirming that it is “committed to enabling the free exchange of ideas, which hinges on providing participants a safe and open space that fosters both rigorous inquiry and compassionate respect.” As the workshop’s coordinator and long-time participant, I believe this gesture of offering a safe space represents the consensus of the workshop’s participants. For me, it was a no-brainer.

Additionally, I will be calling a special session of the workshop where participants can democratically decide if the workshop will offer the oft-demonized content disclosures (popularly referred to as “trigger warnings”). This discussion will be one small part of a much larger exploration of “The Politics of Writing History.” I would encourage all other workshop coordinators to follow a similar path and declare their workshops safe spaces while freely discussing the merits of content disclosures. They should also become certified as safe spaces with the Office of LGBTQ Student Life and seek affiliate status with the Office of Multicultural Student Affairs.

In a strange way, I would like to thank Dean Ellison for prompting this action. His letter to the Class of 2020 has now become a national touchstone, prompting us all to consider a number of vital questions concerning both free speech and academic freedom.

While I cannot speak for the workshop in toto, I felt compelled to follow the lead of a number of faculty members in expressing my own personal concerns with the dean’s letter and its appropriateness. As faculty members made clear, Ellison is not the arbiter of classroom practice. Students and their professors will collectively decide the nature of their pedagogical relationship. All else from the dean is effectively superfluous.

Our professors also remind us that safe spaces, inclusive environments, and decent wages for student workers are things that we, as students, must create for ourselves. Education, like democracy, is not a spectator sport. Safe spaces cannot be not dictated from above nor are they passively received by empty vessels from below. They must be imagined, built, and nourished by participants committed to collective, ongoing action. In this respect, the administration is as impotent as it is misguided.

In terms of specifics, I have yet to hear a compelling argument in favor of un-safe spaces or a lack of content transparency. Can a professor reasonably be barred from telling their class: “This clip contains graphic sexual violence?” Is there evidence to support improved outcomes in pedagogical environments where students are subjected to personal attacks, microaggressions, and open harassment? This does not strike me as a question of political correctness or coddling an allegedly self-indulgent generation. This is a matter of basic human decency, good manners, and common sense.

Contrary to the administration’s implications, the promoters of safe spaces on this campus are not suggesting censorship or a retreat away from difficult conversations. In fact, it is quite the opposite. These difficult conversations can only take place through civility and mutual respect. They require each individual’s identity to be freely expressed in its fullness, without being subjected to ad hominem attacks or charges that one’s social position makes them incapable of making a purportedly “objective” academic inquiry. A truly safe space is the apex of open inquiry and academic freedom—not its antithesis. Safe spaces include otherwise excluded speech. They make a conversation whole.

But this moment is about much more than what constitutes a safe space or the particulars of content disclosures. Also at stake here is a much larger question of the role of the modern university in the 21st century—and who controls it. Why do universities exist at all? To produce cutting edge research to be monetized by the highest bidder? To isolate idiosyncratic geniuses from the rest of society? To generate multi-million dollar salaries to academics-turned-bureaucrats? To enable university trustees to funnel endowment money to their golfing buddies’ hedge funds?

Call me a hopeless romantic, but I still believe that the university is a magical place. A place where the pursuit of tentative truths and the mutual exchange of ideas among and between students and teachers should trump everything. But building such an environment is not automatic. It must be constantly tended to and fought for.

So why would the administration wade into this question at all? Many have speculated that the dean’s letter was an attempt to appeal to politically conservative donors. The plea was certainly a deeply gendered posture signaling that the administration can talk tough, even as it knows full well that the university already supports safe spaces and possesses no mechanism capable of policing their further creation by students and faculty. The role of the administration here should ideally be one of absolute neutrality until an overwhelming, clear consensus of the campus community demands action. For example, it would be entirely inappropriate for the administration to deliberately act against the popular will and interests of its students by hiring a corporate law firm to wage an anti-union campaign against unionizing graduate student workers (which, by the way, it recently did). Students surely know what is best for themselves in this regard.

I am proud to affirm that the U.S. History Workshop is a safe space. We might even believe in love. And there is nothing the administration can do to stop us.

Guy Emerson Mount is a sixth-year Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History, a Mellon Fellow, and the Coordinator of the U.S. History Workshop.