The Maroon does not traditionally endorse presidential candidates. As the University of Chicago’s student newspaper, we tend to focus on elections for student government, as well as state and local elections that affect our Hyde Park and Woodlawn neighbors. National contests, we feel, are already saturated; there is little we could say that has not already been said by another publication.

But this year’s presidential election is different. No alum of the College has come closer to the nomination of a major U.S. political party than Senator Bernie Sanders (A.B. ’64) did in 2016. His 2020 campaign has been even more impressive: He leads the field in fundraising and in polls of the crucial first contest in Iowa, while polling of the general election nearly unanimously shows him defeating President Donald Trump.

At the core of his campaign and his political life has been a courageous commitment to justice which he developed, in part, at the University of Chicago. By his own admission, Sanders was a mediocre student, finding the classroom “boring and irrelevant.” But his time here wasn’t worthless; in 2015, he explained to Time that he “received more of an education off campus than [he] did in the classroom.”

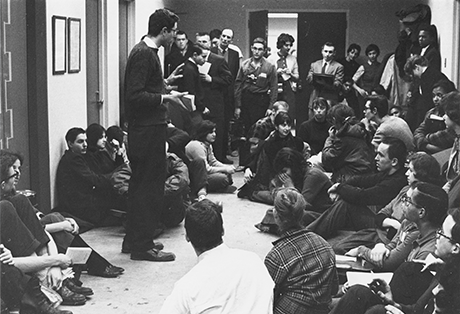

One of the first lessons in that education came in January of 1962, when the University of Chicago played host to one of the earliest sit-ins in the northern United States. Thirty-three students, organized under the banner of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), occupied what is now Levi Hall, demanding an end to the segregation of University-owned housing. Sanders, chair of CORE’s social action committee, gave a speech on the steps of Levi, then led the group up to the office of University president George Beadle, where they remained for nearly two weeks. An agreement with administrators ended the sit-in, and, by the fall of 1963, the University integrated its off-campus apartments.

His time at the University produced the now-famous photograph of a 21-year-old Sanders being dragged to a police wagon by two Chicago police officers at a protest in Englewood against segregation in Chicago Public Schools. Just two weeks later, Sanders—$25 poorer after paying his fine for “resisting arrest”—boarded an overnight bus to D.C. to attend the March on Washington, where he witnessed Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech on the National Mall.

Sanders has credited this time at the University of Chicago with helping him to “look at politics in a new way,” teaching him to recognize the “relationship between wealth, power, and the perpetuation of capitalism.” Sanders’s approach to politics shines through in his recent engagement with the University. In 2017, Sanders called on the University to respect graduate workers’ vote to unionize with Graduate Students United. When the University refused to recognize GSU, the union called a three-day strike in June 2019. Sanders’s campaign sent more than 100,000 emails and texts to supporters in the area, driving supporters from across the city to join graduate workers on the picket lines.

After decades of decline, the American labor movement is experiencing something of a renaissance. Membership numbers, gutted by the decline of industries like mining and manufacturing and further decimated by right-to-work laws, continue to drop. The last few years, however, have seen more workers go out on strike than at any time since the 1980s. American public approval of unions is near a 50-year high, the Fight for $15 movement has seen victory in state after state, and unprecedented teachers’ strikes in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Chicago have captured national headlines.

The labor movement has shown the effectiveness of a politics of mass mobilization, and it needs a friend in the White House. While most Democratic candidates sign on to broadly pro-labor proposals, only one candidate uses his campaign infrastructure to drive turnout on picket lines and collect donations for strike funds. Sanders’s vision of the presidency as “organizer-in-chief” sets him apart from other candidates. It also harkens back to a lesson he learned at the University of Chicago: Change only happens when people are mobilized to take on established interests.

This approach to social change is also apparent in his platform on the environment. Sanders’s Green New Deal proposal is the most expansive of any candidate’s, setting an ambitious goal of 100 percent renewable energy by 2030. Greenpeace ranked his proposal the best out of the field, awarding him the only A+ on their candidate scorecard. But the proposal’s strength lies beyond its technical details. The Sunrise Movement’s recent endorsement of Sanders lays it out: “a world in which we stop climate change…cannot be achieved by one President or even the government on its own. A Green New Deal can only be achieved by building and sustaining a movement of millions of people of all walks of life from all corners of the country.”

On a whole host of other issues, Sanders stands apart from the rest of the Democratic field through his commitment to grassroots organizing. He is the only candidate who continues to fight for Medicare for All, the only one to propose universal student debt relief, and the only candidate with a 50-year record of opposing America’s military intervention in Vietnam, Iraq, Yemen, and Iran. These positions have been criticized as politically unrealistic, but this criticism misunderstands Sanders’s ambitious approach to societal change. Other candidates, most notably Senator Elizabeth Warren, have also presented impressive policy proposals, but Sanders is the only candidate who pairs those with a theory of change focused on building a mass political movement. He recognizes that, throughout history, the kind of structural change he sees as necessary has only materialized when millions of people organize and demand it.

Sanders’s slogan is “Not me. Us.” It’s not just a catchy saying; it reflects a radical reimagining of the presidency as the leader of a mass movement—a political revolution—that is capable of taking back power from the richest 1 percent. That fight against inequality and injustice has been Sanders’s work for most of his life. It makes it easy to believe that Sanders is honest about his goals and intentions as president; we know exactly what he’ll do, because he’s been fighting the same fight since his time at the University of Chicago.

Sanders’s integrity and consistency is a welcome change. His vision of revolution from the bottom up sets him apart from his competitors in the Democratic primary. The Chicago Maroon endorses Bernie Sanders for president.

News Editor Caroline Kubzansky recused herself from this editorial due to her involvement in coverage of the upcoming Iowa caucuses. Associate Arts Editor Alina Kim also recused herself.