Gentrification and UChicago’s Impact on Hyde Park

For more than a century, the University of Chicago has heavily influenced the development of the South Side, which has led to a contentious relationship between the school and its neighbors.

When the University was established in Hyde Park in 1892, the South Side was predominantly white, but the South Side’s Black population grew significantly during the Great Migration. In response, the University of Chicago continually pushed either to restrict or to reverse the growth of Hyde Park's Black community, from the restrictive covenants of the 1940s to the “Urban Renewal” efforts of the ’50s and ’60s.

This spring, the Maroon Editorial Board published a series that contended with the University’s past harms and argued for a path forward that includes reparations and greater community input in development and philanthropic decisions. One piece in particular, titled “It’s Time for UChicago To Rethink Its Development Strategy,” sheds light on the damage that the University’s development plans have inflicted on the South Side and how the University can do better going forward—by incorporating community feedback and protecting affordable housing, for example.

Beyond the University, gentrification has become a pertinent issue in Hyde Park, and one of the biggest flashpoints within the community is the Obama Presidential Center (OPC). The OPC’s proponents view it as a potential engine for development, arguing that the center will provide jobs and raise property values. The opposition is a mix of those who view the OPC as a force of gentrification and those who want to preserve Jackson Park, where the OPC is being built. An article from the Hyde Park Herald, a local paper, titled “In and Around Jackson Park, Opinion on OPC Remains Varied” features a wide range of local views on the issue. Preliminary construction on the OPC began in April 2021.

As an elite, resource-rich institution located in an underserved community, the University of Chicago has the potential to do a lot of good, as do the students who attend it. Another piece from the Maroon Editorial Board series, “To Be a Better Neighbor on the South Side, UChicago Must Begin on Its Own Campus,” discusses ways in which UChicago could leverage its resources to benefit the community.

Student groups have been making an impact on the South Side without direct help from the University. UChicago for a CBA has been organizing in support of Hyde Park residents who would like a community benefits agreement (CBA) to be put in place for the OPC, protecting residents from the ill effects of possible gentrification. UChicago United, a coalition of organizations primarily focused on organizing for racial justice on campus, has been running a mutual aid program that incorporates direct community feedback to make sure that the aid distributed best serves the community. Local organizations operating independently of the University lead the way when it comes to countering gentrification and creating healthy communities. Check out the youth programming by My Block, My Hood, My City, queer community building by the Brave Space Alliance, and environmental justice work done by the Southeast Side’s People for Community Recovery.

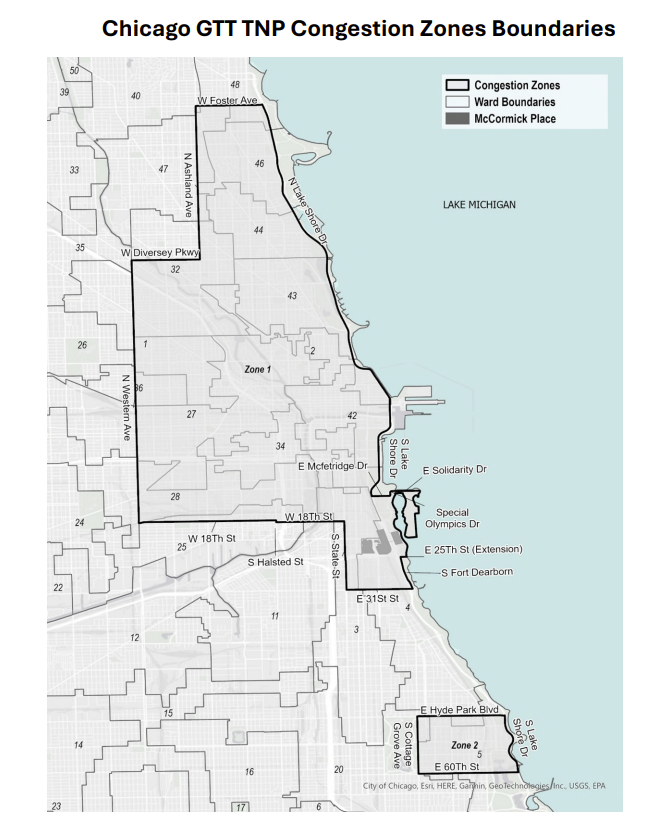

Defunding the UCPD and Over-Policing

Like many other campus police forces, the UCPD has become a flashpoint on campus due to the perception that it lacks accountability and maintains a patrol radius far beyond the edges of campus. While UChicago sits between East 55th Street and East 61st Street, the UCPD’s patrol area extends north to East 37th Street and as far south as East 64th Street, giving it jurisdiction over about six square miles and more than 65,000 Chicago citizens—45,000 more than all UChicago faculty and students combined.

The University’s first security staff were hired at the departmental level in the 1930s, with the first campus-wide force established in 1952. Named the South East Chicago Commission (SECC), the group was heavily involved in the “urban renewal” efforts of the 1950s, hiring off-duty police officers to force out “undesirable” businesses. For those looking for a better sense of the history of the UCPD, this Grey City article is one resource.

The UCPD does not have a sterling record. According to data obtained by The Chicago Reporter, of the 166 people stopped and questioned by the UCPD in ten months during 2016, 155, or 93 percent, were Black, while the population of the UCPD's patrol zone was only 59 percent Black. In 2010, a Black student was arrested in the Regenstein Library for refusing to show ID despite multiple witnesses attesting that the officer never asked for ID.

In 2018, the shooting of UChicago student Charles Thomas by a UCPD officer prompted calls for the UCPD to be abolished. Thomas was shot during a mental health episode his parents believe was brought on by bipolar disorder. On the night Thomas was shot, officers found him roaming a Hyde Park alley with a tent stake, and body camera footage shows Thomas approaching the officer with the stake before he was shot. In response to Thomas’s shooting, UChicago United founded the CNC campaign to advocate for defunding the UCPD. CNC has called for 50 percent of the resources dedicated to the UCPD to be shifted to community-focused programs that target the socioeconomic and health factors driving up crime. In June 2020, the Maroon Editorial Board released a piece titled “The University Must Disband Its Private Police Force.” The piece covers arguments for defunding and abolishing the UCPD in depth. While CNC has many supporters on campus, it also faces resistance, as a Maroon column from last year by Matthew Pinna demonstrates.

UChicago United has gained prominence for organizing multiple protests across campus, including a sit-in at the UCPD’s headquarters last summer. However, the actions of protestors have also drawn criticism. Accusations of anti-Asian racism and harassment were leveled against protestors who occupied the street in front of University Provost Ka Yee Lee’s house. CNC later released a statement disputing those accusations.

The debate over the UCPD’s authority in the South Side and whether it should be defunded or abolished is a heated one across campus. In an op-ed titled “A Peaceful UCPD, If Only,” Benjamin Boyd, a student at the divinity school, details his account of a traffic stop by a UCPD officer that ended in him being tackled and arrested as well as what he believes to be the steps that need to be taken to reform the department. Throughout, the University has continued to maintain that it is open to reforming the department, with the administration organizing town halls and listening sessions on the subject.

The Graduate Student Fight

Since 2007, Graduate Students United (GSU) has been fighting for better pay and labor protections for graduate student workers. While GSU was first created in response to what its founders said was a poor funding package, the organization’s fight has evolved into a battle over whether graduate student workers should be classified as employees represented by a recognized union.

UChicago has so far resisted classifying graduate students as employees, maintaining that work done by graduate students is a part of their graduate education at the University.

In the face of continued opposition from the University, the GSU escalated its actions, staging multi-day walkouts in 2018 and 2019. During the pandemic, a number of graduate students have been refusing to pay the student services fee in an effort to get the University to reduce it and disclose what it funds.

With a return to on-campus life, a more pro-union federal government, and a new University president in Paul Alivisatos—who spent his career at University of California Berkeley, which has a recognized graduate workers union—GSU is hopeful that significant change will occur in the upcoming year.

If you want to learn more about GSU, see “Looking Back and Forward: GSU’s Fight for Graduate Student Rights and Recognition” for more information about the group’s history and goals for the future.

Diversity at UChicago

Like at many other primarily white institutions, diversity in all aspects has been a focal point for both the students and the administration of the University of Chicago. Of the students admitted to the University of Chicago’s Class of 2024, 25 percent are Asian, 10 percent Black, and 15 percent Hispanic. Despite the diversity of its student body, minority students at UChicago have often felt marginalized. A column by Rachel Ong titled “No Longer an Afterthought” discusses in greater detail the Asian-American student experience, and an op-ed by the UChicago Black Graduate Coalition titled “How the University of Chicago Misses the Mark with the Black Community” talks about how the University needs to repair its relationship with Black students and Chicago’s Black community.

UChicago’s faculty is significantly less diverse than its student body. According to data reported by the University for 2019, 16 percent of full-time instructional staff were Asian, while Black and Hispanic staff each made up less than 4 percent. Diversity of tenured faculty is even less, with Asian, Black, and Hispanic faculty making up less than 14, 3, and 4 percent of the University total, respectively. In response to these numbers, a faculty-led effort named #MorethanDiversity has been campaigning for structural changes to the administration in order to promote diversity and equity within the University.

The group has also campaigned with UChicago United’s #EthnicStudiesNow in an effort to establish a fully funded critical race and ethnic studies (CRES) department. While the Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture does offer a CRES major, its lack of departmental status means CRES courses are inconsistently offered because faculty who teach them do so on a voluntary basis. Noah Tesfaye’s column “The Critical Need for a Critical Race and Ethnic Studies (CRES) Department” goes deeper into why many faculty and students believe the University needs a CRES department.

In an email sent to the campus community on September 1, newly appointed University President Paul Alivisatos outlined a series of “vectors of culture and engagement” on which he plans to focus during his tenure. In describing one of these vectors, “Sense of Belonging,” Alivisatos asked, “What else can we do to ensure that our community is diverse, that all students, researchers, staff, and faculty feel that they can speak and will be heard, and that our climate is inclusive and creates a sense of belonging?” As we start the new school year, students and faculty invested in diversity at the University will await answers to this question from administrators.

Free Expression on Campus

Freedom of speech is contentious at the University of Chicago, which has made freedom of expression a core part of its identity. In 2014, former University president Robert Zimmer appointed the Committee on Freedom of Expression and charged it with drafting a statement “articulating the University’s overarching commitment to free, robust, and uninhibited debate and deliberation among all members of the University’s community.”

While the committee’s report never actually mentions the phrase “Chicago principles,” the term has been used since then to promote the idea that the University of Chicago believes in no limits on speech or debate. The University’s stance has prompted both criticism and acclaim from students and faculty at UChicago and other institutions which have adopted the “Chicago Principles.”

UChicago’s emphasis on free speech seems unlikely to shift in the new school year despite a change in leadership. Newly appointed University President Paul Alivisatos said in his September 1 email that freedom of expression will be a core concern of his tenure, asking, “How can the University build on its leadership role as an advocate for and home of free expression?”

The University’s broad stance on free expression has manifested in many politically charged debates about acceptable expression in recent years. After a professor invited Steve Bannon, a former White House chief strategist well known for xenophobic, homophobic, and Islamophobic stances, to speak at the University, debate ensued over whether the University, to quote those who protested the Bannon invitation, “cares more about ‘freedom of expression’ than the lives and well-being of students, faculty, staff, and Hyde Park residents.” The criticism and harassment of a student who had written “I vote because the coronavirus won’t destroy America, but socialism will” as part of the Institute of Politics (IOP)’s “Why I Vote” campaign sparked a debate over whether the University’s atmosphere truly permits all types of speech.

Viewpoints has a plethora of columns and essays exploring the free speech debate. “Instructing Insurrections: How UChicago Can Avoid Creating the Next Ted Cruz,” a piece by Kelly Hui, discusses how the Chicago principles can sometimes be used to mask bigotry as academic debate. Another piece, “A Lesson in Free Speech” by Alexa Perlmutter, talks about how free speech allows ideas to surface so that they can be debated and critiqued.

Greek Life

Greek life at the University of Chicago, like at many other universities, has been marked by controversies. Last spring, some UChicago community members blamed fraternities for a spike in coronavirus cases—and subsequent lockdown of campus—that the University initially attributed to fraternities but later linked to “multiple clusters, starting with individuals who were unknowingly infected over break.” And in 2019, UChicago’s chapter of Kappa Alpha Theta sorority was accused of excluding members of color from its recruitment process, which led to calls to disband the sorority and a subsequent mass exodus of its members.

Sexual violence on campus is a major issue for students in and out of Greek life, but for many, it is inextricably tied to the presence of unrecognized fraternities at UChicago. Recognized student organizations (RSOs) like the Phoenix Survivors Alliance, which provides support to survivors of sexual violence, have been voices in favor of Greek life recognition, especially in the wake of alleged sexual assaults in fraternity houses and by fraternity members.

Many students believe that issues with Greek life at the University of Chicago are inflamed by the University’s refusal to recognize fraternities and sororities. Recognition by the University would give administrators a way to exercise oversight on Greek life organizations. A piece by the Maroon Editorial Board portrays this refusal as an attempt by the University to enable it to solicit donations from alumni who were in Greek life while evading blame when scandals arise.

The range of proposed solutions for the problems associated with Greek life is wide. Some advocate eliminating fraternities and sororities entirely; one former president of the Panhellenic Council argued that “the system would rather stick to its roots than address inequity.” Others are pushing for these institutions to change themselves, as Viewpoints columnist Ketan Sengupta does in his column, “How Greek is Greek Life, Really?”

Mental Health

For years, activists have been pushing the University to make changes to both its academic and campus life policies in order to improve student mental health. While administrators responded by making changes to the academic quarter and providing resources for students, a perceived lack of student input in the process has often led to solutions that are widely panned as ineffective or even harmful.

In response to complaints about the toll of the academic year’s pacing, the University decided to lengthen the breaks between terms by shortening each quarter by one week. The move was met with widespread criticism, and many called for greater student input in the decision-making process. The Maroon Editorial Board released a piece, titled “For Truly Effective Mental Healthcare, Listen to Students,” calling on the administration to incorporate the input of students and coordinate with student-led mental health efforts that had seen success.

The situation for many neurodivergent and disabled students is also precarious. A Grey City article published earlier this year reported the difficulties faced by several students with disabilities who sought accommodations from the University. Many students said that successfully getting an accommodation often depended on the goodwill of professors. Others criticized the University’s decision to stop offering part-time status in 2015.

To some, COVID-19 and the measures required to mitigate the worst effects of the pandemic exacerbated student issues. A Grey City piece from April details some of the mental health struggles that students faced during last year’s winter quarter. Some students reported feeling isolated and depressed due to a lack of social contact.

UChicago’s “where fun comes to die” culture has also been to blame. Last year, a newsletter from Woodlawn Residential Commons offered a line of finals week advice that summed up UChicago’s stress culture: “Loss of sleep is temporary…GPA is forever.” The backlash from students also encapsulates the mental and physical toll that the academic load and culture of the University can take on students. In her Viewpoints column “The Detriments of the New Dean's List,” Elizabeth Winkler talks about the effect the University’s academic awards system has on students, while in “The Danger of the Life of the Mind,” Ong discusses how UChicago’s academic culture impacts students.

Despite criticism leveled against the administration, UChicago’s students have been able to find support among their peers. Active Minds, an RSO on campus tied to the national Active Minds nonprofit, seeks to “empower university students to speak openly about mental health in order to educate others and encourage help-seeking behavior.”

Pre-Professionalism and “Quirkiness”

When James Nondorf was appointed the dean of college admissions and financial aid, a University press release touted his “emphasis on matching the right student to the right institution, while building cultural and intellectual diversity.” For the Class of 2013, the last one admitted before Nondorf took over the admissions office, the University’s acceptance rate reached a then–all-time low of 26.8 percent, 13 percentage points lower than the rate from four years before.

Now, years later, members of the community continue to debate the impact Nondorf the former Yale University associate director of admissions, has had on the University’s culture. The University of Chicago’s acceptance rate was 6.2 percent for the Class of 2024, only 1.3 percentage points greater than Harvard University’s.

Regardless of whether admissions policies are to blame, many undergraduates believe that the University’s culture has changed. “A Multistory Failure: How UChicago’s Housing Plan Disappoints” by Luke Contreras laments the new mega-dorms; “Scav Deserves to Be Saved” by Brinda Rao talks about how interest in core Chicago traditions has declined; “Why We’re All Miserable Careerists” by Tesfaye discusses the rise of pre-professionalism among the student body and the University’s role in encouraging it; and “The Problem With Mimicking Harvard” by Ruby Rorty highlights how the administration’s attempts to match the Ivy League “dilutes the wacky, wonderful culture that led us to choose UChicago.”

Those preparing to mourn the loss of our school’s identity can take solace in the arguments put forth by “Weird Social Science”, a piece published by the Maroon Editorial Board in 2010, the beginning of the University’s shift in admissions strategy. “We know, because the admissions statistics bear it out, that College first-years are better and better prepared to study here. What we don’t know—and shouldn’t presume—is that we’ve arrived at the College in the gloaming of some Golden Age of intellectual purity. Like any top school, the U of C has always attracted students with a range of interests and ambitions.”