Dispatches From a Fishless Lake

The fish of Lake Michigan and the people that once depended on them have become the victims of an underwater ecocide.

Chicago skyline from the point

October 27, 2022

If you, like me, have an itch to uncover our city’s piscine history, go to the Chicago History Museum’s online photo archive and type “smelt fishing” into the search bar. About 40 images will appear, black and white photos from the ’60s and ’70s. All are taken at night, when artificial light sources can be used to lure smelt, a small migratory fish, towards the surface. There, they are easily netted, or “dipped.” The dippers’ windbreakers and wool hats attest to the month, April—its chilly but increasingly warming nights cuing the smelt into their yearly migration up to the Great Lakes tributary rivers they spawn in.

On that April 22nd, 1976—the day most of the photos were taken—fishing groups stretched all the way down the North Avenue Pier in Lincoln Park. A broad slice of humanity is on display. One group has built a bonfire out of those flimsy wooden fences you can still find on all the Chicago beaches. Four young children sit beside it on a wall, framed by the skyline, paying rapt attention to a story being told by a standing man. Another group divides their labor between netting the smelt and immediately charcoal-grilling them, the latter job belonging to a modest-looking pair while their grinning friend, dapper in his white-trimmed leather jacket and sea captain’s hat, commands the former.

In another image, a father and his sons run down the pier with buckets in their hands, faces giddy. Apart from the rest, a small group of three sit by the light of only one lantern, casting long shadows over the pier. Two of them, one silhouetted and one drenched in the lantern’s white light, sit and face the third, who is the picture of concentration as he crouches over some small tool or implement. Two lines extend off the pier and into the water that blends into blackness with the sky. The thawing waves lap, and the smelt flit and turn below, while the lights on the edge of the city twinkle coldly and far away.

As it did on this night, fishing has signified community, sustenance, and ritual to generations of Chicagoans. A lived connection to the lake endured even as skyscrapers surged into the sky and concrete choked the marshy shore. But beneath the waves, an ecocidal drama played itself out. Its initiator was commerce and progress, its characters are obscure aquatic species, and its conclusion is a lake left barren. That’s what we have left today.

***

Lake Michigan, before settling into its current basin, was cyclically pushed southward and pulled northward by the oscillating continental glaciers of successive Ice Ages. Over thousands of years, the lake became populated by the “hardy fish and other aquatic species that had been dwelling in the melted waters just beyond the glacier’s reach,” journalist Dan Egan writes in his 2017 book The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. And when the most recent of the glaciers receded about 4,000 years ago, these species came to constitute the ecosystem of Lake Michigan as well as the Great Lakes at large. Cut off from the Atlantic Ocean by the rapid currents and steep ledges of Niagara Falls, the lakes’ ecosystem was protected from any incursions by oceanic species.

Like any healthy ecosystem, the food web of the lake was complex. Everything depended on algae-like phytoplankton, and the tiny zooplankton that ate them. Small fish ate this plankton, and bigger fish ate the smaller fish, but some larger fish also ate plankton. Some smaller fish preyed on the eggs and young of bigger fish, while a few focused on insects. Add mollusks and crustaceans to the mix, and you’ve got a tangled web of cohabitation, predation, and codependence featuring some commonly known species—perch, bass, and muskies—some that have since been decimated by the ecological changes that humans have wrought—fatmucket clam, lake trout—and some that live on, hiding in the deep water’s obscurity—burbots, sculpins.

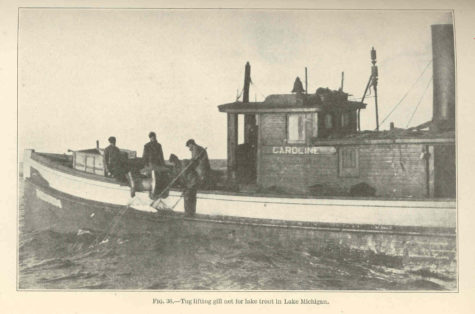

But of all the lake’s species, lake trout was king. Trout, which still live in the lake, can grow up to and live for decades. In years when food is scarce, they stop growing to save energy. In years of plenty, they resume devouring everything in their path, from plankton and insects to other fish. This incredible flexibility and longevity allowed the lake trout to form specialized colonies “uniquely adapted to thrive in the areas it colonized,” Egan writes. Bottom-dwelling trout developed eyes closer to the tops of their heads; those near streams adapted to migrate upstream to spawn like salmon, while those in deep water grew more body fat to remain buoyant near the lake’s floor. The region’s early European settlers gave these separate colonies names like yellow fins, buckskins, grease balls, and moss trout. Initially, the most effective method these men had for catching the trout was to let an angry hooked trout drag the boat around until it grew tired enough for the men to pull it out of the water. Native American tribes would net and spear the trout when they migrated to shallow water to spawn every fall, using the upcoming winter weather as a natural storage mechanism. Even as commercial fishing took off and led to concerns about overharvesting, yields remained remarkably high—by Egan’s account, 8 million pounds of lake trout were being pulled out of Lake Michigan every year at the turn of the 20th century. But the lake’s diversity and bounty were tenuously protected by just one single geologic formation—Niagara Falls. Under the banner of progress, humans soon overcame this barrier, changing the lakes for good.

***

The first character in the ecocidal drama is not a fish, but Canada’s Welland Canal. Built between St. Catherine’s and Port Colborne in the province of Ontario, it finally gave Lake Ontario and Lake Erie a connection by water other than the Niagara River and its famous falls, impassable to ships. Since the canal opened in 1829, it was enlarged and deepened throughout the following decades, allowing organisms native to the Atlantic Ocean, St. Lawrence River, and downstream Lake Ontario to use the artificial navigation channel to enter the remaining four Great Lakes’ isolated ecosystem.

The sea lamprey was the first truly destructive example of these Welland Canal invaders. With its eel-like body and perfectly round, perpetually open mouth that’s lined with dozens of tiny teeth, it’s a scary fish. And it’s a real threat, too: It uses this mouth to latch on to other fish and bleed them out until they die. In the Atlantic Ocean, it’s kept in check by larger predators like cod. But as soon as it got into Lake Erie, then Huron and Michigan, it was open season. What became of the resplendent, kingly lake trout? Lake Michigan’s catch decreased from 6.5 million pounds in 1944 to a mere 342,000 pounds in 1949, and none at all five years later, with the lamprey to blame.

The next character in the drama is a person: Vernon Applegate, a University of Michigan doctoral student. Applegate knew that most of a sea lamprey’s life is spent burrowed into the bank of a stream, sucking tiny bits of food out of the water until it grows large enough to go out into the open water and feast on larger fish’s blood. So he camped out at one of these streams in northern Michigan, intent on finding a weakness in the invader’s life cycle that could be targeted, controlling the lamprey infestation. Egan writes that the scientist would chase the parasites “up rivers through the night and into dawn with flashlights and a notebook,” and that Applegate “built outdoor pens to watch them breed.”

Applegate was obsessive, “living on cigarettes and aspirin.” He tracked their migration schedule to the week, and realized that the most effective control would be a poison, a “lampricide” that would kill off the invaders in their streams before they ever got to the lake, leaving other fish unharmed. So the mad scientist started another multi-year project, this time at a remote research station on Michigan’s Lake Huron shoreline: testing thousands of chemicals, sent by chemical corporations all over the country, by mixing them into a fish tank containing two juvenile lampreys and two native fish. The 5,209th chemical was the one that finally killed the lampreys and spared the others. By 1967, the poison had driven the lamprey population to a 10th of what it had been, and it remains at that level today thanks to a long-running lampricide program administered by the United States and Canada.

Enter the alewife. This fish had snuck in through the Welland Canal with the lamprey. Too small for the bloodsucker, and completely unchecked by the decimated lake trout and whitefish, alewife populations exploded: Scientists estimated that they accounted for 90% of Lake Michigan’s fish mass in 1965. Great Lakes fishermen attempted to make an industry out of this new invader as East Coast fishermen had done for centuries, but the lake proved not to be salty enough to sustain the alewife long-term. They came to shore another way: foot-deep mats of decaying sludge washed up on the beaches of Lake Michigan, including Chicago’s entire urban lakeshore. The city had to use bulldozers to dispose of them. Morale was low, and some park workers even quit in disgust.

Then came the salmon. Ignoring a federal project reintroducing lake trout to the now-cleansed Lake Michigan, the State of Michigan’s Head of Fisheries Howard Tanner brought salmon eggs from the Pacific Northwest and started stocking the lakes with these instead. He was focused on boosting recreational fishing and believed the non-native salmon provided a more interesting fight when hooked than the trout did. The salmon would also gobble up what was left of the alewife, preventing another beaching event. The stocking program proved highly successful, with the Pacific newcomers establishing their own runs up local rivers and filling up the empty lakes, overrunning the native holdouts that might have finally had a chance at post-lamprey resurgence. Tanner didn’t particularly care: By the 1970s, recreational fishing in Michigan had skyrocketed. Piers all along the state’s enormous coastline became, essentially, constant tailgates while lakeside communities raked in the profits of tourism.

The act of environmental engineering didn’t stick. In the late ’80s, the salmon started declining. So did the alewife, though there were fewer salmon to eat them. So did all the native holdouts, though there were fewer alewives to prey on their eggs. The culprit was an invader that put the nail in the ecological coffin: zebra mussels.

This mussel is native to Ukraine’s Dnieper River estuary, a region known for its oscillations in salinity. This made them well-equipped to travel in the ballast tanks of ships, floating in the water that ships take in for balance. Oceangoing vessels did this in ports all over the world, and then flushing and replacing the water at port in the Great Lakes. Once they made it over, zebra mussels spread across Lake Michigan’s bottom like spilt water on a tabletop, eating up all the plankton and starving the fish further up the food web. The related quagga mussel did the same thing 10 years later, even spreading to deeper areas that had been inaccessible to the zebra mussel. “Lake Michigan,” University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences ecologist John Janssen tells me, “is basically just a giant mussel bed now.”

***

Go to the lakeshore, and you will see the traces. Washed up on the beaches, along with the driftwood, bottle caps, and plastic straws, are snaking lines of the mussels’ tiny shells. Step in the water and you’ll remark how clear it is. That’s on account of the mussels filtering out all the microorganisms that typically cloud fresh water. If you swim out to a buoy, a water intake station, or a pier, you’ll find them bristling across the surface, too small to harvest and eat but large enough to cut and pierce your skin. And if you notice any dead shorebirds, know that the new water clarity helps the growth of algae that deoxygenate Lake Michigan, creating ideal conditions for the proliferation of the avian botulism bacteria.

Various fishing traditions have suffered as the lake has become barren. Ojibwe and Winnebago fishermen sitting in birch-bark canoes once speared fish by torchlight and wove nets out of nettle plants to catch a large part of their yearly sustenance. Even as settlers encroached and environmental problems mounted, tribes forcefully defended their treaty-stipulated fishing rights. Gone are the days when South Side steelworkers would take their skiffs out on weekends and fish to supplement their wages. Before World War II, most Chicago fishing outfits belonged to this category. And if you go to Diversey Parkway bridge across the Chicago River, you won’t find fishing trawlers unloading their smelt bycatch and frying it for passers-by in what one Chicagoan recalls as a stream of “gruff talk and jabs and winks.” Under combined pressure from environmental degradation and the recreational fishing lobby, the Illinois Department of Conservation limited lake fishing licenses from 45 to just three, instituting a lottery for the coveted spots and driving many family operations out of business. Now, to the average University of Chicago student and most Chicagoans, Lake Michigan exists for recreational purposes only, severed from our food system and economy by the waves of invasive species that have left it empty.

There are always those who try to gather something from the wreckage. Through all the ecological turbulence, a federal lake trout reintroduction program has been stubbornly running on Lake Michigan for decades. The fish is a draw for Chicago anglers, as any cursory glance at the bullishly alive Chicago fishing community on Reddit will reveal. Raising fish in hatcheries and releasing them for recreational anglers to catch is no replacement for a functioning ecosystem. But in 2001, Janssen was finally able to record the first evidence of natural lake trout reproduction in the lake, zebra mussels notwithstanding. He continues his lake trout monitoring to this day, and was preparing to go on a multi-day boating trip to investigate potential trout spawning areas in Lake Superior when I spoke to him.

He explains that in a lake, this warped invasive species can have good consequences, too. One of the Great Lakes’ new arrivals is the round goby, native to the same European waters as zebra mussels, and a prodigious eater of the mollusks: It’s already succeeded in driving the scourge out of Wisconsin’s Green Bay. Unexpectedly, native bass really took to the gobies, so much so that bass fishing in Lake Michigan is on the up. Howard Tanner’s salmon still have their runs, too, and the Chicago Sun-Times’ outdoors column reports on prize catches made by urban anglers throughout the summer.

Some commercial fishing operations have held on. Most are in Lake Superior, though one in Lake Michigan still fishes for the elusive burbot, a bottom-dwelling relative of cod that is barely researched due to its inaccessible habitat. The more common catches are familiar lake trout and whitefish, battered but not beaten in northerly Lake Superior, where low calcium levels make zebra mussel growth difficult. A taste of these resilient fish—and a connection to the lake that goes beyond wading in, deciding it’s too cold, and wading back out—can be found just a few Metra stops south of campus at Calumet Fisheries, an old-fashioned smokehouse perched on the side of Calumet River.

The place is surrounded by creaking old bridges, highway overpasses, and post-industrial junkyards, surviving with the same kind of tenacity that drives scientists like Janssen back to the lakes they’ve lived their lives by. Founded in the 1920s under a different name, Calumet Fisheries survived the deindustrialization in South Chicago that deprived it of steelworkers stopping for a bite after their shift; it has flourished in the 21st century despite the bleak, disused landscape that has set in around it. Part of that is thanks to a feature on Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations, but most of it has been on account of the place itself. The customers are loyal and have been coming for decades. It has deep local roots, embodied by store manager Javier Magellanes, a young man only a couple years older than some of the students reading this newspaper. He started working at the smokehouse as an after-school job while growing up in the neighboring East Side neighborhood and rose through the ranks until the store was entrusted to him. He takes me to see the main component of the store’s stubborn excellence: the smoking itself.

Great Lakes trout, whitefish, and smelt, along with imported shrimp and salmon, are brought on the previous afternoon in a small truck. It sits in a secret brine overnight until the worker with the morning shift comes in at 5 a.m. to start the smoking process. The fish is sliced into what’s known as a “darne” shape at this point: the bones and organs taken out so that the cross-section of the fish resembles a tooth or a horseshoe. It’s hung from strings on metal rods near the top of the little brick smoking shack next to the shop (made from the “good” Chicago bricks of the early 20th century, Javier says). Oak logs are put on a movable grate sitting on the ground and pushed inside with the flame burning. The door is closed: This part is for heating up the inside of the smokehouse enough to cook the fish. Once it’s cooked, the worker dons heavy-duty work gloves and protective glasses to replace oak with the smokier cherry. It’s periodically pushed in and out of the smokehouse while the door is kept open, giving the fish its smoky taste after it’s been cooked through. I ask Javier if he can stand to eat fish in his free time anymore.

“Yes, I never get tired of our fish,” he says. “But bonfires are the real problem. I smell like smoke every single day. I do laundry all the time. When a buddy invites me to a bonfire in his yard on the weekend, I just can’t bring myself to go. I can’t be smelling like smoke on the weekends too.”

***

Calumet Fisheries smokes up some delicious fish, but it’s paltry consolation for the cold, hard fact: The piscine history of Chicago is an ecological catastrophe. Think about it too much, and the waves start to lap with the silence of annihilation. The fishermen on the piers lose their idyllic sheen and seem more like Sisyphus than like Hemingway’s Old Man. The stray birds probably eat more pizza crusts than they do fish. And the supermarket fish we eat for dinner—Alaskan salmon, Icelandic cod, Mississippi catfish—is just faceless fillet, pastiche product.

The joy that Calumet Fisheries or a big salmon catch may bring is put in perspective by something called ecological baseline shift: What seems natural, healthy, and good to us is just a shadow of what there was as little as one lifetime ago. Compared to the days when European explorers wrote of catching 50 trout in a day, some “weighing half as much as man,” perhaps we’ll never be able to speak of a true ecosystem in Lake Michigan again.

Is this a surprise? An ecosystem with humans in it reflects the needs of those humans. Native peoples and early settlers depended on the lake for survival, so they kept it resilient and plentiful. Later commercial fishermen were feeding a booming nation; they pulled as many fish out as they could while the lake seemed to just keep on giving. We don’t need the lake’s ecosystem at all, with our transnational trade networks and supermarket habits. So most people didn’t blink an eye when it went barren. The ones that were affected almost seem like relics, weird holdouts.

In the struggle between nihilism and hope about the fish of Lake Michigan, perhaps it is fitting to end on these holdouts. One of them is an unidentified person in a red jacket, captured in a photo for the Chicago Sun-Times outdoors column, walking along the grand embankment between Shedd Aquarium and Adler Planetarium. It’s nighttime, and the city skyline glimmers in the background. They’ve got quite a setup: a picnic table, bags of food, fishing poles, buckets, a generator, and a grill. The photo was taken in April 2019. Is the water below empty? Maybe. Does it support a healthy ecosystem, streams of springtime smelt? Unlikely, but year to year, who’s to say? It seems that the lake behaves in the same ways this city does—always changing, always getting wiped clean just to be repopulated again. We have our fires and floods, the lake has its mussels and lampreys. Our riots and displacements are the lake’s disasters and die-offs. The smelt itself is an invasive species, one of the first, breaching the Welland Canal as early as the 1910s. That unsettling fact doesn’t bother the dippers; should it bother us? We mourn ecocide, but most of us are an invasive species too, raising a palatial boomtown on top some of marginal Potawatomi hunting land, erasing the prairie under a metastasizing array of smokestacks and roads, a needlework of billboards and apartment buildings. In their shadow, the artificial is disguised, the natural is muddled, and the smelt dippers will surely keep on dipping: two invasive species united in a primeval ritual. It’s absurd, tragic, and beautiful, and in Chicago, it might be the best that we can get.

Bill Wade / Nov 14, 2022 at 9:22 pm

OK, soi dissant Jack Walter, you did good here with the writing. And the research relit all my memory light bulbs about Lake Michigan’s commercial fishing from the late 1940’s onward.

Paul / Nov 13, 2022 at 4:22 pm

Excellent article. This belongs in the New York times where people actually read the news. I’m a native Hyde Parker, and also spent my summers in Michigan on the Lake Michigan shore. I was an avid fisherman, catching Perch, hunting for Lake Trout and Brown Trout in the many streams that drained into the Lake. I remember the Smelters at the Point. And I am a long time customer to Cal City Fisheries. The change as you describe is so relevant, our Lake is so clean and clear and unfortunately devoid of life. But the days of the Alewifes washing up on the beaches by the thousands, making a day at the beach smelly and difficult to wade in the water without being touched by dead floating fish and clumps of algea-we called it seaweed- are long gone. So true that our Great Lakes are now a balancing act for industry, water usage, recreation and trying to clean up the mistakes of our interventions of the past. You didn’t mention the Asian Carp invasion…they probably already exist in some tributaries into the Lakes, they most likely will not invade the deep cold waters of the Great Lakes to be a nuisance, but there will be others that will preservere.

Christy Anderson / Oct 27, 2022 at 9:28 am

What a great article! Excellent research and a great read!!