Getting Bi

On being a queer woman in a heterosexual-presenting relationship, the commodification of female sexuality, and attraction as a possible means to an end.

November 15, 2022

Coming out to my mom the first time was a nonissue. I was 12 years old, a defiant hand placed on either of my cocked, knobby hips, emboldened by Hayley Kiyoko’s This Side of Paradise and Panic! At The Disco’s “Girls / Girls / Boys” from atop the staircase of my childhood home, the details and contours of which I can barely remember today. Like a queer, middle-school-aged Gatsby, I addressed my audience of one, the announcement scrambling out of my throat and descending the staircase like a mad, scrappy dog that can barely catch its breath, panting: “I like girls!” My mom kissed my cheek, rubbed my back for just a moment, and released me to do whatever preteens are meant to do after they come out.

The second time, I sat in the passenger seat of her teal-blue Honda CR-V, shaking like a leaf in the McDonald’s drive-thru. I was 17, miserable, headed to Chicago in a few months and almost two years into my first serious relationship, a relationship I hated. Maybe I just hated who I was when I was with him.

I whimpered it out in one cracked, high whine, and my mother looked up from her crumpled-up “$1 large fries! Two for $6! Five for $5!” collection with a bewildered expression. In retrospect, it probably sounded like a prayer, but I think I was more so asking for permission or forgiveness: permission from her, forgiveness from myself.

My mom blurted out a half-laugh, half-yelp that came together to form a wide and white-eyed “I know!”

We drove home with Frozen Cokes.

This column isn’t about my mother, nor my breakup, nor the fantastical queer escapade I embarked on when I was finally freed from the jaws of both suburban Michigan and a guy who played Snow Patrol during sex (please laugh, because I didn’t). There was no girl-like (“girl-like-like”?) romp, no playing catch-up, no soft limbs or sweet hair or shared closets. I started seeing my current partner and boyfriend during move-in of first year; at the time of writing this column, our one-year anniversary is tomorrow. I love him deeply and publicly.

(I’ll reject the promiscuity stereotype, but you’ve got me on serial monogamy.)

Two years after coming out to my mother a second time, I am a bisexual woman who has never been with another woman.

On Wanting Women, Wanting Women

I grew up in a deceptively conservative Detroit suburb before moving to Chicago. Under those circumstances, I cared very deeply about who knew what about me. And, in thinking so much about the image of myself I was putting out into the world, to make sure I made sense to other people, I failed to ever really make sense of myself, to myself.

While my family’s influence and love kept me on the path of self-acceptance (or at least not utter self-hatred), taking proud and casual ownership over my queerness is very much a “college thing.”

Explicitly, my relationships with men have never—and never will, as they exist and propagate throughout time in my memory—given rise to the same scrutiny, harassment, or overt homophobia I’m certain I would have experienced in some capacity if I had ever had a girlfriend. I just feel that’s something important to get out early, for the sake of understanding where this piece is coming from. Being heterosexual-presenting in my relationship contains specific privileges that others have articulated far better than I ever could, at the very least with more tact than “I don’t look the part.”

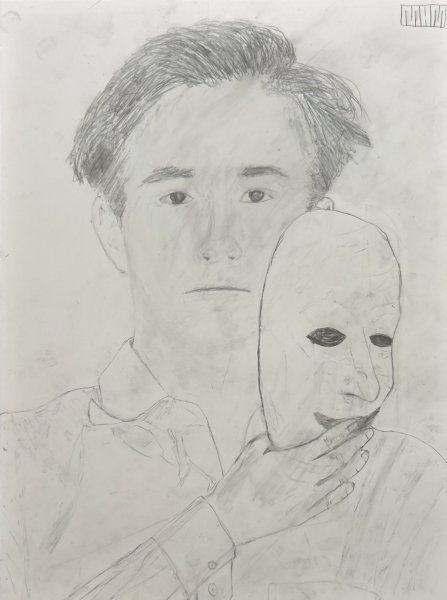

And yet, the “looking,” the part-playing, the performance element to being the bisexual girlfriend is something I’ve struggled with. In previous relationships, my sexuality transformed into this mutable currency, this transactional quality others felt the right to inspect, discuss, and share.

When my ex gleefully announced that he had outed me to his mother, I felt bile come up my throat. I asked him how could he do that.

It’s not a problem, he said. Because I’m with him.

I’ve also had straight people express, often within minutes of finding out my sexuality, that I just don’t look queer, especially with a boyfriend and all. I struggled hearing the exact same thing from LGBTQ+ people, who for so long I so desperately wanted to lift me up by my chin, hold my face in their hands, and approve of me. This led to a different sort of part-playing, where I wondered if I would be taken more seriously as a queer person if I dyed my hair swamp green (note: an ongoing personal battle I’m just one bad midterm way from losing) or gave myself a stick-and-poke on my inner thigh.

I always chastised myself for thinking like that; if that’s what I think I need to do to “be queer,” I’m really no better than anyone else.

(I was also just too scared of making any big and dramatic physical changes to go through with any of them.)

But still, perhaps I could be a caricature of myself, one that is easy to understand at face value, instead of having to stomp my foot on the ground like a toddler to get people to not just accept me, but to listen to me.

But is part-playing so terrible if you’re a convincing enough actress? There are times I’m perfectly fine with distilling myself down to my essentials: enthusiastically pointing out a girl’s piercings and tucking my hair behind my ears to show off mine; lifting up my jeans to reveal the yellow stitching on my worn-out Docs; carrying crystals in my overalls; making a point of saying “partner.” These are the moments where I see someone else’s face shift, just slightly behind the eyes, and the conversation adjusts to a more comfortable position.

And yet, even in the accepting queer settings I participate in, I feel like an intruder. The tension isn’t because of my boyfriend, past or present, but more my lack of experience making me feel like a Peeping Tom. There are experiences I simply cannot relate to—and it’s no one’s job to fill me in on the footnotes—and that dissonance I experience when communicating my queerness to my peers is necessarily alienating. In observing queer joy, queer love, queer woe, and queer pissed-the-hell-off, I’m actively trying to make sense of it all as though I were looking through wax paper.

On Billy Squier’s “Everybody Wants You”

Yes, the quick fix to all of this is kissing some girls, at least N greater than or equal to one girl. No, everything I’ve written up to this point is not some displaced dissatisfaction in my current or past relationships with men.

To expand on what I’ve already said about part-playing, I think it’s impossible to air out my grievances about being a queer woman without talking about the space I take up in others’ minds as a sexual creature.

People who are concerned with who I am and who I’m not having sex with should go out and have more sex. The fetishization of not just bisexual or queer women, but the completely lascivious way people try to dissect female sexuality at large, bleeds into how others assess the “validity” of someone’s sexuality.

We must realize and recognize that mistreatment of the bisexual woman is not entirely rooted in homophobia—which is certainly true—but also the misogyny that attacks all women.

The perceived “promiscuity” of the bisexual woman is born from the same source that shames the heterosexual woman; in both cases, her crime is her explicit, active control over her choice of romantic and sexual partners. The “fear” of the bisexual woman cheating is not about any lack of loyalty, but a lack of dependency on male validation or attraction to feel worthy or self-assured; this venom seeps into how, oftentimes, the first insult slung at a self-sufficient woman is regarding her face or physique. Queerness being equated to specifically same-sex sexual partners is all too reminiscent of the tallying of a woman’s sexual partners.

Female bisexuality, in being viewed as an opportunity for the sexual advancement of others (“My girlfriend and I saw you from across the bar, and we really like your style!”), rather than for the bisexual individual, is necessarily a remnant of women being viewed as sexual objects. Of course, I cannot speak to what this means for the fetishization of bisexual men, except that if you pursue bisexual partners under the sole pretense that your chances of scoring are higher, à la Ken Kwapis and 2000s romantic comedies, he’s just not that into you.

On Attraction and Sexuality, On Means to an End

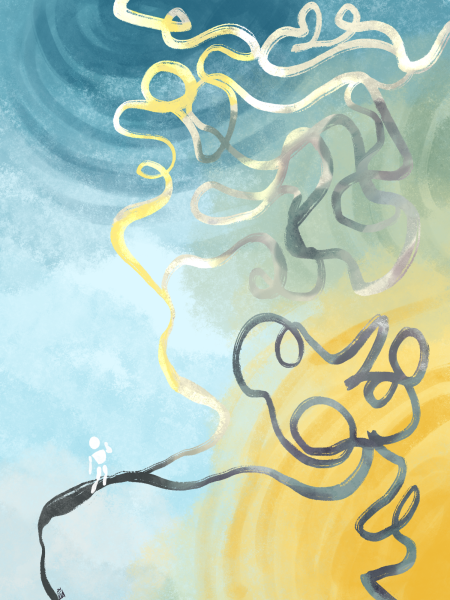

If I reject sexuality as being a good indicator of one’s person, do I perceive attraction as just a biological factor that compels us to “The One”? Absolutely not. In saying both attraction and sexuality are mere means to an end, one is effectively pushing forward the relationship- or monogamy-centric perspective of valid love, rather than appreciating raw, beautiful, terrible, and tender queerdom as a non-linear, impermanent force.

When the girl I crushed on at freshman year journalism camp crosses my mind, I make a silent ask to the universe for her to please be happy and well.

I once asked my middle school friend group what they would do if I liked girls, and watched as they grabbed their trays and saran-wrapped sandwiches and scooted away to the far end of the lunch table. I’m kidding, I’m kidding, I’m kidding.

My childhood best friend and I met at an annual summer art program, and when she came back the next year to tell me her first girl crush was me, my face glowed as we cackled.

I cannot reach down into my throat and extract these parts of me, lay them out in front of me, and say they only happened to serve as a means to the end that is my current partner.

However, my greatest grievance as a bisexual woman is others’ expectations of proof, which I’ve faced from both straight and LGBTQ+ individuals. The current, collective view of sexuality as something to be depicted, portrayed, or performed means I occupy a permanent liminal space between fetishization from straight people and insufficiency by LGBTQ+ people (in the absolute worst cases, of course).

Instead, I prefer to see my sexuality as a vehicle by which I find my person, or my people—a part of myself I love for who it allows me to be, and for who I will be in the future because of its guiding hand. I am surrounded by beautiful queer friends, and I frequently find myself sitting on their floors, gazing fondly at their fondness for one another. It’s in those moments, bathed in purple, that I think to text my boyfriend.

Eva McCord is a second-year in the College.

aurora / Nov 16, 2022 at 9:36 am

beautiful. overjoyed to be on of the queer friends you sit on floors with <3