New Pritzker Dean Mark Anderson Wants Med School Without Tuition or Student Debt

Anderson, who started in October, also serves as the Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs and the Dean of the Biological Sciences Division.

On October 1, Anderson began his tenure as executive vice president for medical affairs, dean of the Division of the Biological Sciences, and dean of the Pritzker School of Medicine.

December 1, 2022

The Pritzker School of Medicine at the University of Chicago is the most diverse school in U.S. News and World Report’s top 20 medical schools and one of the most generous in its financial aid offerings, with 92 percent of students receiving tuition aid.

But for new Pritzker dean Mark Anderson, that’s not enough.

“I want to capture the value of the centennial of our school to try and move us to an even better place in terms of tuition support,” Anderson said, speaking of Pritzker’s upcoming 100-year anniversary in 2027. “My goal would be to move the University into tuition- or debt-free scenarios so that we can even further expand the diversity of our students.”

On October 1, Anderson began his tenure as executive vice president for medical affairs, dean of the Division of the Biological Sciences, and dean of the Pritzker School of Medicine. He replaced Kenneth Polonsky, who is now a senior advisor to the president of the University.

Anderson joins UChicago after nearly a decade at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where he most recently served as the director of the Department of Medicine, the William Osler Professor of Medicine, and physician-in-chief of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Prior to his time at Hopkins, he served on the faculty at Vanderbilt University and the University of Iowa College of Medicine.

Anderson hopes to bring to UChicago the broadened diversity and equity practices he implemented at his previous roles, particularly those at Johns Hopkins. “At Hopkins, not to oversimplify, but there are many similarities [with UChicago] between the vulnerable populations that surround the medical school and the long and sometimes complicated relationship of those populations to the medical school,” Anderson said.

Anderson made sure to highlight how his former colleague at Hopkins, Sherita Golden, now the Vice President and Chief Diversity Officer at Johns Hopkins Medicine, shaped his perspective on equity and community practices.

“She pointed out that the [hospital] was more than the faculty and it was even more than the nurses. Because of the structure, it involved lots of people who lived in our community—people who transported patients and were medical assistants [and] environmental services workers,” Anderson said. “There were almost 6,000 employees and we started to focus on this broader group to create engagement through a mission-values exercise that was broadly inclusive, and I think successful, through a series of discussions with various groups called Journeys in Medicine.”

The program created a forum for Johns Hopkins faculty and staff to share their experiences as underrepresented individuals while also connecting them with local leaders, such as members of religious communities, police, and university faculty and staff.

“Some of this was really pretty hard to hear, but I think it ended up engaging us more broadly, including as a faculty and as learners,” he said.

Speaking of how he wants to apply lessons from Johns Hopkins to UChicago, Anderson said, “I want [us] to be a more effective partner with the South Side of Chicago and make sure that we’re authentically engaged with the population…but I also want to make sure that people know the really remarkable things that are already happening.”

Anderson also feels expanding UChicago’s base of care is important—a task UChicago Medicine has already begun to undertake with the construction of a new $633 million clinical cancer center. “I think a real point of pride is building the first freestanding cancer center in the whole Midwest right here in Hyde Park.”

Before becoming a physician scientist, Anderson grew up with much exposure to health care. He grew up in Rochester, Minnesota, home to the world-renowned Mayo Clinic—a nonprofit academic medical center that integrates health care, research, and medical education. His father worked there as a consultant, publication editor, and professor, and his paternal grandparents were also both physicians. “It was hard not to be thinking about medicine,” Anderson said.

Despite his family history, Anderson did not originally want to pursue medicine. “My initial predilections were to go into law to do something that wasn’t so predetermined, and I loved history and political science. Those were my first majors in undergraduate,” Anderson said. “But I think I was drawn in by several factors, one of them for sure just being so interested in biology and the kind of discoveries that were starting to occur at that time.”

Clinically trained as a cardiologist, Anderson completed his internal medicine residency and fellowships in cardiology and clinical cardiac electrophysiology at Stanford University after earning an M.D.–Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota in 1989.

For nearly 30 years since then, Anderson has led research funded by the National Institutes of Health focused on heart failure and arrhythmias. His research profile consists of more than 160 peer-reviewed publications.

As his career progressed, Anderson came to especially value academic medicine. “I could try and improve the human condition through reducing suffering, understand[ing] the unmet needs, [and] using science as a tool to gain a deeper mechanistic, molecular-level understanding of how things worked.”

A new challenge Anderson and his colleagues have had to tackle is the burnout facing medical workers on the front lines of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. “It just goes on forever,” Anderson said. “Especially at the beginning of the pandemic, when we didn’t have a good sense of how the virus was transmitted, that was even scarier.”

Burnout in health care professionals remains an unresolved task. “There [are] not simple solutions. I think part of it is acknowledging the value of teams and what people do and making sure that people have access to wellness resources and engagement so that they can talk to their supervisors in a candid, safe way.”

Beyond the stresses of being on the front lines, the pandemic brought social and political turmoil that resulted in less uptake of the unprecedented tools, like vaccines, that were developed to combat the virus, Anderson . “I think the failure to really broadly uptake some of these great treatments is partially a failure of better communication.”

Other than recovery from the pandemic, Anderson also hopes to strengthen the Pritzker School’s collaboration with other UChicago divisions and other Chicago-area research universities. “Biology and medicine are generating tremendous and rich datasets that, until very recently, hadn’t been that interesting outside their communities. But now with the growth in data sciences and the power of computing, I think we’re seeing a lot of interest by adjacent or non-traditional allies,” he said.

Through this research, Anderson hopes to advance patient care—what he considers the backbone of the UChicago medical system.

“That is what creates the revenue streams to support education and research and engage more effectively with the broader university and all its assets,” Anderson said. “I want to make sure that the health system prospers because that’s how we actually touch people.”

Patrick J. O'Meara / Dec 3, 2022 at 7:03 am

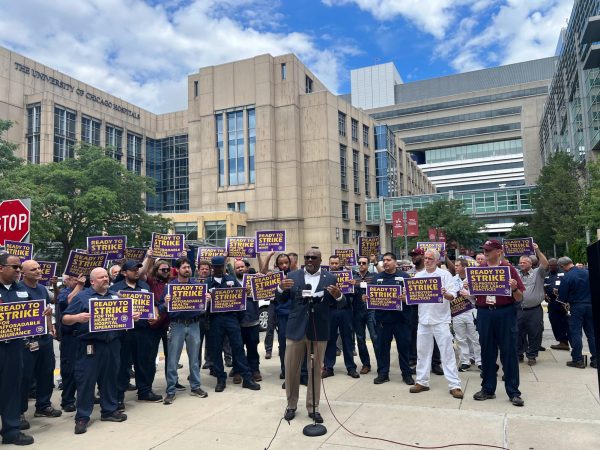

WHY NOT USE U OF C

$11.6 billion ENDOWMENT