Comer Children’s Manages Surge of Respiratory Virus Infection Cases

Children’s hospitals around Chicago are dealing with an unpredicted level of respiratory virus infections, including from the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Doctors at Comer Children’s, a pediatric hospital affiliated with the University of Chicago, note a connection between the RSV spike and the shift away from COVID-19 measures.

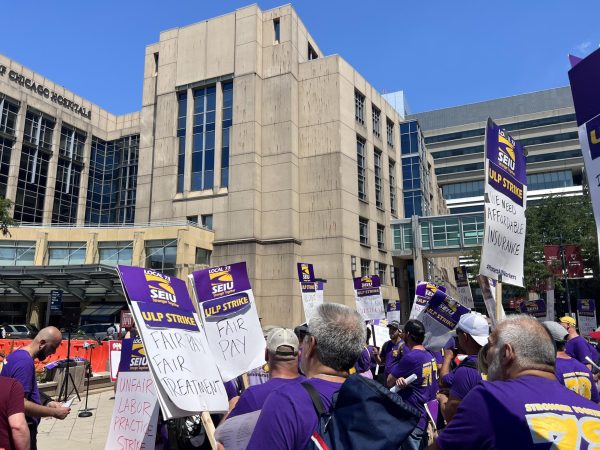

University of Chicago Medicine

Comer Children’s Hospital.

January 26, 2023

The Situation at Comer

Since September, Comer Children’s Hospital has been battling an unusual peak in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a type of respiratory virus. The peak presents a challenge as the hospital navigates a staff shortage and limited bedspaces for pediatric patients.

While the occurrence of respiratory virus and influenza infections are commonplace and seasonal, hospital senior administrators say that the cases started appearing earlier and at a higher rate than in previous years.

Physician-in-Chief at Comer and Chair of the Department of Pediatrics at UChicago Medicine Dr. John Cunningham painted a picture of the condition: “On several days in the last few weeks, we have run out [of beds]. We’ve been very close to not having any pediatric intensive care beds in the state of Illinois. And indeed, on some days in [November 2022], we’ve had to refer patients to Wisconsin or to other surrounding states.”

Although Comer caters primarily to the South Side, it has had to accept a large number of transfers from other hospitals as a tertiary referral hospital. This designation means that Comer provides specialized care that is not available at many surrounding hospitals.

With an increase in patients, Comer has made adaptations to strategically manage and even expand the capacity of its intensive care unit. A leadership team, which meets multiple times a day, has implemented some measures to make operations smoother. One of such measures is moving patients with less pressing medical needs out of the emergency room into the clinic building in order to free up bed space in the E.R. The E.R.’s urgent care section has also been moved to the ambulatory clinics to create more space.

Despite the challenges of the RSV peak, the hospital endeavors to support its staff. Associate Medical Director of Infection Prevention and Control Allison Bartlett said, “It’s a really tough time, and we are aware that people are getting exhausted. But we are also really proud of all the work that everyone is doing.”

Comer has instituted an incentive bonus program in which staff who pick up extra shifts are paid bonuses. More shifts have been added for residents and attending physicians to pick up so as to relieve their coworkers.

Jeff Murphy, vice president of Women’s and Children’s Emergency Services and Associate Chief Nursing Officer, said that leadership essentially amounts to “taking time during the day to listen to staff, getting together with them, hearing what they need, [and] ensuring that they have the tools necessary to do their job.”

However, the hospital struggles to hire contract nurses. In anticipation of the rise in respiratory illnesses, Comer routinely hires contract nurses in the winter to bolster its staffing. But the Windy City might not appeal to many contract nurses. “You can imagine every children’s hospital in the country is going through what we’re going through. And if I’m a travel nurse, it’s much more appealing to go to Palm Springs in November than it is to come to Chicago in November. So we have not been able to get any contract labor. And so what we have is what we have,” Murphy said.

Role of the Pandemic

Experts at Comer attribute the surge of RSV and similar respiratory viruses to various pandemic-related factors. For one thing, the pandemic caused a blow to children’s influenza vaccination rates. As a result, children—particularly those who are immunocompromised or asthmatic—are more prone to being admitted for respiratory infections. Second, Cunningham mentioned that the hospital is seeing more older kids, referring to those between the ages of three to four, which he attributes to the fact that lockdown and social distancing measures prevented many children from being exposed to and building up immunity against the viruses.

“We’re seeing a lot of children from previous years…who need exposure. So we’re not just seeing zero- to two-year-olds. We’re seeing three-, four-, and five-year-olds with RSV, which is pretty unusual. Because many of our children were cocooned or protected from all kinds of respiratory infection[s] because they were wearing masks and washing their hands, we didn’t see the same level of illness from respiratory illness in the last two years, in 2020 and 2021,” Cunningham said.

Third, while handwashing and masking practices that were emphasized because of COVID-19 curbed the rates of infection in 2020 and 2021, these practices have since been relaxed.

“We have kids who did not get their first RSV infection in those first two years…we started seeing these increases in infections around the time kids went back to school or childcare. So—[there was] a lot more mixing of kids with respiratory viral illnesses. And we have gotten rid of all of our masking and social distancing and all the other measures that are helpful to prevent respiratory viral infections,” Bartlett said.

According to Bartlett, the public could take certain initiatives, such as resuming masking, to reduce rates of infections, but balancing public health and politics is tricky.

“Clearly, our neighbors and our friends in our community are very tired of the masking and hand washing, et cetera, that was so important in reducing the risk of COVID-19 infections in the last three years. But as we come out of the all-pervasive pandemic and we reduce those safety measures, we’re going to see more and more respiratory illness,” Cunningham said. “We need to think about as a society, should we make sure that we mask up during the winter to prevent transmission of these viral issues, viral agents which really affect individuals who are at risk?”

Murphy added that such conversations are complicated by the erosion of trust in the public healthcare system. “I think we as a healthcare system need to figure out a way to rebuild that trust. And how do we engage, you know, political leaders and our community?… I think that’s where the challenge lies,” he said.

Looking Forward

As of November 2022, rates of infections were dropping after a few tumultuous weeks, but Comer’s staff is not wholly optimistic.

“It’s stressful to be in this position not knowing how the winter is going to play out, but I’m not particularly optimistic. And my colleagues have been working so hard and are so dedicated, but everybody’s getting appropriately really tired,” Bartlett said. “I don’t know how we can stay in this space.”

With the flu season in effect, they are expecting an influx of patients. At the same time, the staff shortage at Comer is not likely to end. In fact, availability might even be harmed as staff fall ill during the winter. According to Murphy, “we’re entering the time of year now where we start to see our own staff getting sick with influenza colds. It’s just that time of year. And that always strains the system.”

Still, Murphy expresses his gratitude towards the effort Comer has made in tackling this challenge. “I am profoundly proud of the people who have, really over the last two months, done everything possible to get every last child into that building that needs our care.” he said.

Phoenix / Jan 28, 2023 at 8:20 pm

Why didn’t the reporter approach the nurses union for comment on staffing and bed capacity? I’m pretty sure “Florida is warmer than Chicago” isn’t the full story on why contract nurses aren’t picking Comer.