Hyde Park’s Unassailable Pastime

A love letter to Hyde Park pickup soccer, the sport that will never die.

February 10, 2023

At the University of Chicago, little is sacred. The College does its best to restrict the aspects of campus that bring students any semblance of joy. The beloved Botany Pond has been closed since the autumn, for reasons that seem vague at best. Library hours have been reduced; coffee shops have closed down. Even the songbirds that dot the main quad during autumn nights head south the moment winter in Chicago rears its ugly head. They know better than anyone that nothing lasts here.

Nothing, that is, except Hyde Park pickup soccer.

Pickup soccer has existed for decades in Hyde Park, and continues to persist today. A few times a week, friends and strangers, old and young, from far and wide, band together in the neighborhood to play the world’s game. The schedules of UChicago’s athletic facilities are pored over in order to find time and space to play, and eager participants are informed of possible times and locations via Facebook, WhatsApp, or email list. Eventually, a time and location will be determined. Someone will bring a ball, and if no cones are available to use as goals, jackets and water bottles will do.

The University, as is their wont, tries its best to restrict the amount that pickup is played on campus. UChicago’s athletic facilities, particularly for open-field sports like soccer, are pitiful in number, and the three available to pickup each present various problems. Stagg Field is closed in winter, and almost always occupied by varsity sports teams during fall and spring. Campus South Athletic Field, the turf field across from Woodlawn Commons which is a favorite of pickup groups, is likewise closed in winter, and often reserved by varsity or club teams during other seasons. (It should be noted that pickup soccer players, in not enjoying the organizational status of RSOs such as club soccer, cannot reserve the fields for themselves, and must look for gaps in the schedules to play.)

The Henry Crown Field House, used during winter when the weather and lack of open facilities makes it impossible to play outside, does not allow persons not directly affiliated with UChicago inside without a membership fee, which presents a problem for the dozens of Hyde Park residents or recently graduated students looking to play. Although pickup soccer’s numbers are reduced in Crown, this location also suffers from overcrowding, as basketball, volleyball, and club and varsity soccer players jockey for space on the second floor.

Nevertheless, pickup soccer survives through it all. The various existing groups scour the schedules for free space, pouncing like leopards when the time is right. Gangs of players politic and make compromises with other groups in order to carve out fields. During autumn quarter, for example, after the ultimate frisbee RSO reserved South Field during Tuesday and Thursday evenings, a treaty was quickly negotiated where pickup was able to claim a third of the field for themselves.

These negotiations often lead to friendships and feuds with the other athletic groups on campus. The frisbee RSO might be loyal friends, for example, but the same cannot be said of the varsity lacrosse team, who during summer would not allow several pickup soccer stalwarts onto the field to warm up until sometime after their scheduled slot expired.

The club soccer RSO, on the other hand, are pickup soccer’s congenial coworkers, often playing at the same time at the same locations. Sometimes, when facilities are busy, the two groups might scrap over the right to play in the same area; nevertheless, relations are generally good.

Even after finding grass, turf, or hard ground on which to play on, there are further logistical concerns which foreshadow the beginning of a pickup match. An odd number of players from which to make even teams is a common problem—usually, one side will just take the extra player. There is often adjusting of teams during games, as people come and go. Similarly, the borders of the playing field are tinkered with as the game grows and shrinks.

When games get large enough, some kind of uniform is necessary so as to identify one’s teammates. In a world where no one is organized or devoted enough to bring pinnies, this usually takes the shape of light- versus dark-colored shirts, but depending on the kind of shirts people have on, this too might be shifted by the populace. (“Blue and black shirts against white and red. Good?” Good.) During sessions where more players show up than there is space to accommodate them, three or four teams might be organized, switching off every two goals, or every 15 minutes.

It is important to acknowledge the swiftness and relative ease with which these logistics are straightened out. These groups, often made up of total strangers, are able to come together and create compromises that suit every one of them. The U.S. Congress would blush from the ease in which a group of random Hyde Park residents, most of whom barely know each other, are able to sort their shit out when collective legs itch to kick something around. As Henry Davis writes in his excellent essay on the politics of pickup, “Where there is no system of coercion, it becomes necessary for everyone—yes, every single person—to agree to a plan of action that no one violently objects to.” There is a kind of political identity forged on the field before every match; the body politic must act together in order to ensure its survival (have a good game).

Indeed: Hyde Park pickup soccer is a societal sphere Rousseau would have been proud of. (Given he was Swiss, he probably wouldn’t have made a bad midfielder, either.) Once you step onto the pitch, there is no hierarchy; the masses rule without any monarch present to shape their thinking. There is culture, there is tradition, and there is a kind of common-sense law. Nothing else governs pickup players.

The logistics that playing pickup entails may sound tiring to those who just want to kick a ball around after a long day of class, and there is no doubt they can be frustrating. There’s nothing worse than an evening when, after all the work that comes with organizing a game, you change, throw a water bottle and cleats into your bag, and make the walk over to the field before realizing there’s no damn space to play.

Those moments, though, are rare. When the pickup community sets out to play, there’s not much that can stop them. When the field they intend to play at is taken, they, like songbirds, migrate to greener pastures.

In fact, it is during moments like these, where the group faces what is in essence a struggle to survive, when the collective spirit of Hyde Park pickup soccer shines through the brightest. I’ve hitched a ride to Stagg Field from South in the station wagon of a middle-aged British man, and used my free Lyft rides to transport gaggles of unknown grad students.

Those involved in Hyde Park pickup soccer are nothing if not stubborn. Weather conditions rarely deter pickup. During my first year at the College, I came out every week to play scrimmages on the Midway Plaisance—already a terrible place to play, because of how bumpy the grass is—during a wet autumn when significant patches of the field had turned to brown mud. During one memorable game we ran about on the Midway in snow and hail. “These are the real players, the ones who came out today,” someone declared at one point. I was just glad I’d brought a hat and gloves.

It was the coronavirus, perhaps above all else, which showed off the indomitable nature of Hyde Park pickup. UChicago, unsurprisingly, kept the outdoor as well as indoor fields, closed to non-varsity sports for all of 2020 and 2021. It was tragic—but the decision still didn’t derail pickup entirely. I remember routinely scaling a construction fence on Woodlawn Avenue with a group of bravehearted undergrads so we could sneak into South Field and have a kickabout. Often, we got kicked out by University staff. Once, the campus police even showed up, flanking the field from the outside while we collectively shat ourselves. We couldn’t leave through either entrance without going up to them and owning up to climbing the fence. They rolled their eyes, told us not to do it again, and let us off the hook.

Pickup games are played in bitter cold, searing heat, and heavy rain. A few Saturdays ago, a group spent 30 minutes shoveling snow off the ground just so they could get a 5v5 going. I’m a little embarrassed to say I didn’t show up to that one.

Thanks to an ever-gentrifying neighborhood, a lack of initiatives taken by the University, and the unfounded neuroticism that still plagues many students, there exists a deep disconnect between UChicago students and the neighboring communities of Hyde Park and Woodlawn. Pickup soccer, in all its human splendor, is an activity which works, completely unintentionally, to stitch this disconnect closed. The sport has introduced me to a plethora of grad students, faculty, and locals I would have never otherwise met. The sport is also definitionally diverse. That soccer is multicultural is obvious, but what is less so is that owing to the relative lack of American appreciation for it, that same multiculturalism persists down to the level of pickup soccer. This is especially the case in large cities. New York City pickup is famously ruled by Arabic and African players; in Chicago, Indians, Black Americans, Koreans, Chinese, and Mexicans are all frequently found dotting the pitch. It often feels as if all the ethnic tensions in the world could be solved not in the boardroom but in and around the 16-yard box.

Come to a large Hyde Park pickup game, then, preferably an outdoor one in decent weather. Breathe in the grassy air. You might see a couple of old men huffing about, with their shorts pulled high and their shirts tucked in. They’re not much for dribbling—or any kind of running, really. But once in a while they’ll ping a pass across the pitch that would make Hakim Ziyech proud. You might see young kids, thrown onto the pitch by dads hoping they have a prodigy on their hands. Everyone goes easy on them. You might see some incredibly fit people running around, with enormous calves. The men rip their shirts off the moment it gets warm enough to do so. You might see some people who aren’t so fit. There are short people, tall people, attractive people, ugly people. People yelling at each other in Spanish, or in Chinese. All are welcome.

Soccer is a unifying force, no matter your background or your personality. The talkative and trusting introduce themselves and have chats with fellow players during warm-ups. The sport that binds you is an immediate conversation starter—even if that conversation just entails throwing some digs towards someone else’s jersey. And if you’re not inclined to talk, if you don’t say a word to anyone before or after the game, well, no one will judge you for it. Messi barely talks, either.

Despite the inherent joy and catharsis that comes with pickup soccer in Hyde Park, the games themselves are not celebratory. Far from it. The matches start quickly, with sweat and anger mingling in the afternoon air. Your blood starts to pump; the bruises and aches you had this morning fade in the face of the field in front of you. The narrative arc is in motion, and for all the collective spirit we share, we are helpless to stop it. Goals and tackles fly in; high fives are doled out for each player. There are a few players who might go down easily for fouls, and sometimes arguments break out regarding a certain tackle. Personal vendettas might emerge: He tackled me hard? He’s going to get tackled hard in a minute.

There are injuries, no doubt. Bruises, turf burns, and sore muscles come with the territory, but occasionally, you’ll pick up something worse. My leg once got badly tangled up with an opposition player as I was sprinting after the ball. He got up fine, but I badly messed up something in my right leg. I walked with pain for a few weeks, and my pickup career went on hiatus. Even scarier was a concussion I received as a first-year, after getting bowled over by a big Brit. My nose exploded with blood. The guy didn’t even apologize. “Football is not a matter of life and death,” the Liverpool manager Bill Shankly is rumored to have said. “It is much, much more important than that.”

But all the adversity, in the end, just makes one more convinced that pickup in Hyde Park is destined to live forever. The moments of beauty that pockmark pickup matches are why the community turns out every week, through all the hardship, battered and bruised. The pulling-off of an absurd skill, the scoring of a perfect team goal. Getting the ball off a really good player, or a really bad player scoring a great goal. We are put on this earth not to live but to feel alive, and I have never felt more alive at the University of Chicago than after whacking one into the net from 20 yards away and hearing the friends and strangers around me yelp with appreciation.

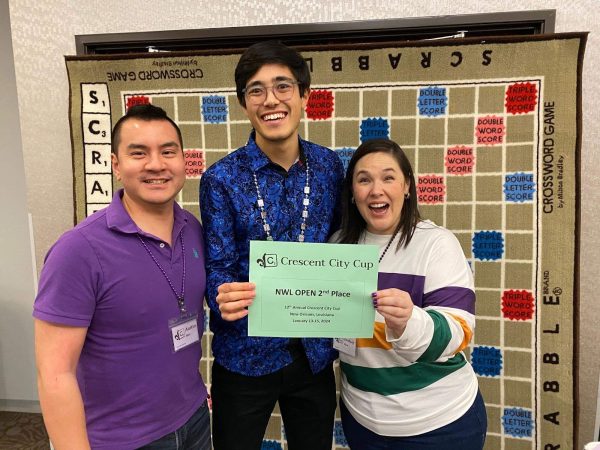

All photos by Finn Hartnett.

David B. Tick; AB '79 / Feb 15, 2023 at 12:02 am

A personal perspective:

As an undergrad who played on the varsity for four years (1975-1979), pick-up soccer was never really a consideration as formal and informal varsity participation commandeered virtually 100% of what little athletic recreational time I was able to steal from the rigors of UChicago college academics.

After graduating and moving to the near West side for four years of medical school, my pick-up soccer play took place outside of Hyde Park, and in the much larger and significantly more expansive and diverse world of City of Chicago pick-up soccer.

It was after that, when I returned to Hyde Park for four years of combined medical and pediatric residency, that I developed a true devotion to and appreciation for Hyde Park pick-up soccer. During the weeks from early April to late November, there were few obstacles capable of keeping me away from an at least weekly and more often daily couple of hours with my fellow die-hards on one or another of the pitches. Just finishing a grueling 36 hour shift on call in the hospital with literally no sleep? No problem! Nothing substantial to eat in the past 2 days? Child’s play! Suffering from an emotional crisis after losing a 15 year old child to some horrible death? Nothing more psychologically therapeutic than blocking a firm shot with your face. Confronted with a choice between devoting rare, precious down time either to the company of a nice looking young lady or instead dribbling a soccer ball with a bunch of smelly men? The choice was obvious and easy. It is no wonder I didn’t get married until I was 30!

And it is equally no wonder that I played pick-up well into my 50’s, only giving it up eventually and regretfully because of two badly torn rotator cuffs. Now that I am on the “other” side of age 65, there are many things I no longer do for one reason or another. Of them all there are none I truly miss the way I miss pick-up soccer.