The Strange Intimacy of Gameday at UChicago

Attending a regular-season varsity sports game at the University is a quiet, dreamy affair. Where have the fans gone? And who are the ones that remain?

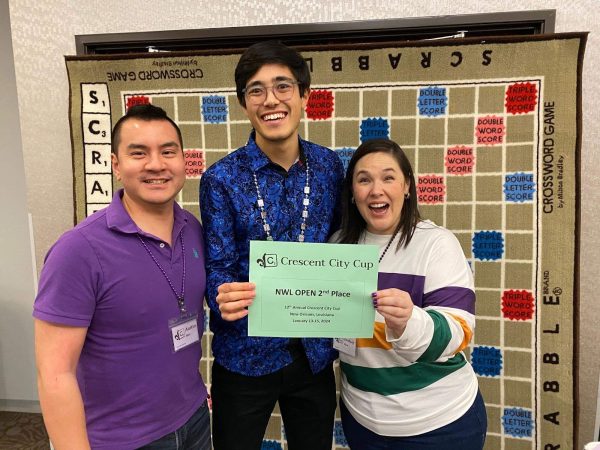

A small crowd gathers to watch the UChicago softball team take on Lake Forest at Stagg Field.

May 11, 2023

“Gameday culture” and “the University of Chicago” are two terms that sound a bit strange if used in the same sentence. Unless they are student-athletes themselves, the majority of UChicagoans don’t concern themselves with following or attending varsity sports. You might come out to a game or two if you have a friend on the team, but few become regulars, willing to turn out for both games of a Sunday baseball doubleheader or for a midweek lacrosse match.

UChicago athletic events come without tailgates, without memorabilia, and, generally, without mascots. (Director of Sports Information Nathan Lindquist told The Maroon over email that Phil the Phoenix only attends “select games, mostly football home games.”) Credit must be given to the UChicago Pep Band, who occasionally play at football and basketball games, but on the whole, there are few fan or College-associated activities surrounding the events. Asking undergraduates to describe sports or gameday culture at UChicago, the most common reply is “what culture?”

Looking back through the history of the University of Chicago, its lack of gameday hubbub comes as little surprise. UChicago has a long, deliberate history of deprioritizing athletics, beginning with Robert Maynard Hutchins, the University’s fifth president, who in 1939 canceled UChicago’s football program altogether. “Football has the same relation to education that bullfighting has to agriculture,” he remarked at the time. The original Stagg Field, which had a capacity of 55,000, was demolished, and the Regenstein Library was built on the ruins. The varsity football program was not reinstated until 1969; the current iteration of Stagg Field holds 1,600.

Still: Where there are people, there is culture, and so gameday culture at UChicago cannot be said to not exist.

On Sunday, April 23, a small crowd gathered at Stagg Field to watch the UChicago softball team take on Lake Forest College in the first game of their Sunday doubleheader. The afternoon was cloudy and gray, and the temperature hovered around 45 degrees; not beautiful weather by any means, but fairly representative of an average day in Hyde Park.

Around 15 UChicago fans, the vast majority parents or friends of players, occupied the third-base bleachers. They were outnumbered by about 25 parents supporting Lake Forest, who sat on the first-base and some of the home-plate bleachers.

“I come to every softball game,” said third-year Erin Ku, whose girlfriend, as well as a few other friends, plays on the varsity team. On this particular afternoon, Ku reclined on the first row of the bleachers, watching UChicago and Lake Forest battle. Asked whether the softball games ever draw significantly larger crowds than the 35 or so total fans who had turned out for this game, she answered in the negative. “It’s only been the parents…and then a couple friends here and there.” Looking around her, she added, “This is honestly one of the bigger turnouts.”

The Lake Forest dugout chanted and sang incessantly during their half-innings at the plate (“Elena!” to the tune of “Tequila!”, and so on). The Maroons were a bit more restrained in cheering their hitters on, although they treated the crowd to a solid rendition of The Neighborhood’s “Sweater Weather”—echoing middle infielder Madeline Murphy’s walk-up song—whenever the first-year stepped to the plate.

Kim Tatro, a former DIII softball coach at Lawrence University, and current Director of Athletics at Lawrence, was also at the game. She cited the busy schedules of UChicago students as a reason why so few turn out to the school’s sports games. “I think with success comes maybe a bigger fan base. But, you know, let’s be honest, students at Chicago have a lot going on,” she said. “If they don’t have a vested interest in the team, maybe it makes it a little bit more of a challenge because there’s so many other things they’re doing.”

Tatro is well-connected in the softball world; she had come to the game to catch up with friends on both the UChicago and Lake Forest coaching staffs. Although she is retired from coaching, she still enjoys attending softball and other DIII athletic events. “I just like the balance of DIII athletics… It’s not all about trying to go professional. That’s not the goal, the goal is to get a great education and have some fun along the way,” she said.

The question comes to mind, then, whether UChicago’s lack of gameday support is a byproduct of its DIII status. DI schools put many more dollars and resources into making their teams and facilities top-tier; it follows that this emphasis on sports would lead to a rise in fans among the student body. But UChicago reports below average attendances even among fellow DIII institutions, most of which possess far fewer students.

UChicago’s total enrollment of 16,274, including 7,526 undergraduates, far surpasses the average total DIII enrollment of 2,615. Nevertheless, the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) reported that in the 2021–22 season, 211 people on average attended UChicago men’s basketball games, below the DIII average of 249. The football team drew 1,113 people per game in 2018 (the last year with NCAA records publicly available), well below the DIII average of 1,705. Women’s basketball was the only sport that drew above-average DIII attendances: The 2021–22 team drew an average of 190, compared to a national average of 152.

The NCAA does not publicly list every DIII university’s average attendance for baseball, softball, volleyball, and men’s and women’s soccer, but they do release the top 25 average attendances for each sport. Needless to say, UChicago does not rank anywhere among these lists.

Tatro speculated that UChicago being located within a large city may be part of what hurts the school’s attendance rates. “There are some small towns where the college is it. That’s the only game in town…so they get a lot of community support. Obviously, a big city like Chicago is different,” she said.

Jennifer Zvokel, who lives in Indianapolis and was present at the game with her husband to cheer on their daughter, pointed out that UChicago’s international reach also means that not as many parents are able to show up to sports games than at a typical DIII school. “I think a lot of other DIII schools, the athletes are quite often from the same geography. Our team…we’re the closest parents geographically. And we’re two and a half hours away.”

People trickled in and out of the bleachers. The game was an exciting and tense one, fueled by good pitching—the Maroons and the Foresters were still tied, 3–3, by the end of the seventh inning. At this point in the game, only two sets of parents and one younger couple supporting a sister remained on the UChicago side of the bleachers. After the eighth inning, three more UChicago students trickled in. They looked lost, although they eventually sat down and watched with the rest of us.

The Lake Forest parents in attendance now greatly outnumbered the UChicago support, which gave the home game a strange atmosphere. Did the Foresters simply have more loyal fans? More local families?

Ku speculated that the Lake Forest parents had helped drive the students to the game. First-year Ally Khoshabe, who had come for a few innings in the middle of the game to cheer on a roommate and who has also attended football, soccer, and volleyball games, said that it is not uncommon for more fans to show up for the visitors than for UChicago. “I wouldn’t know about these games unless I knew people on a lot of the teams. And I have no other reason to go,” she added. “It’s not like people go just for the sake of it.”

Khoshabe attended an Illinois high school where athletics were taken far more seriously than at UChicago, and is of the opinion that the school should do more to get people to attend the games. “I think there are things that can be done to make people more aware about our sports,” she said. “I know our men’s [soccer] team went to nationals, and UChicago really didn’t put anything [out] about it. I thought that would be a chance for people… just to be aware [that] they could watch it on a livestream.” She suggested that the school send emails promoting sports games on campus, though in the same breath she acknowledged that the College sends out “a ton of emails already promoting things.”

The softball game rolled on. The temperature had dropped as the sun sank low in the outfield; parents huddled under blankets and sipped tea for warmth. Chicago’s unfriendly temperatures present another reason why crowd numbers can be low at sports games. Khoshabe stated that the volleyball and basketball crowds are generally larger and livelier than the softball crowds, simply because the games are indoors. A sunny day outdoors will always convince more fans to show up than a grizzly one. Tatro echoed this sentiment. “When I think about spring sports, I think it can be very weather driven,” she said.

Second-year Paige Heffke struck out Lake Forest’s Emmie Nyen to retire the side in the top of the ninth, and the Maroon players around her let out a roar of approval. Heffke had pitched the entire game up to this point; this was her tenth strikeout, and her 134th pitch.

DI sporting events obviously offer a completely different kind of atmosphere than those at UChicago. There are massive stadiums which hold tens of thousands. There is coverage of every game in the student newspaper. There is a massive amount of resources and facilities given to the teams (UChicago students would be shocked to learn, for example, that Northwestern has a dining hall and a “nutrition center” exclusively for student-athletes).

Ku describes attending a football game at the University of Missouri: “You wake up at six, you tailgate. You go to the pregame tailgates, and everyone walks to the field together. 90,000 people, just like, flocking, and then the stadium’s filled. It’s just crazy. Everyone’s geared up… Everyone knows the chants. The marching band is there. We don’t have any of that.”

UChicago’s athletics scene lacks the kind of organized, orgiastic, tribalistic madness that DI sports provides, and this is a fact mourned by some. But there are positives to UChicago’s small, close-knit crowds and more relaxed sporting environments.

Zvokel, for one, opined that the varsity softball team did not mind the atmosphere of UChicago athletics. “I think that the girls that came here to play were coming here for the academics and the ability to continue playing a sport they enjoy, without that sport, like, kind of owning them. I think they knew what they were signing on for,” she said.

Another detail Zvokel noted was that UChicago athletics teams will often turn out to one another’s games, hawking programs and gear to parents and fellow students. There is clearly an intimacy that comes with athletics at UChicago that is impossible to find at a DI institution. Athletes play not with their future careers in mind, but simply to play, to exist. “The different sports support each other,” Zvokel said.

So, it goes. UChicago walked off Lake Forest in the bottom of the ninth. Outfielder Ava Sinai lined a single up the middle, scoring pinch-runner Nicole Wong from third base and giving the Maroons a 4–3 victory. The UChicago dugout let out a united cheer. So, too, did the home crowd that remained.