On November 30, the world stopped turning for the approximately 250 students of Earth as a Planet: Exploring Our Place in the Universe (PHSC 10800) when the professor Fred Ciesla sent an email titled “Important: Moon Journal Grades.”

While on the surface, Ciesla’s email and what prompted it seemed like a run-of-the-mill academic integrity scandal, the uproar that ensued was anything but.

A professor in the Department of the Geophysical Sciences, Ciesla created Earth as a Planet nearly eight years ago and has taught it every autumn since. The class, which fulfills a physical sciences requirement in the Core for non-physics majors, has a reputation for being an “easy A,” but course reviews suggest otherwise.

“This course was tougher than I thought, a lot more math on [the assignments] than I expected,” one comment from autumn 2022 reads. “Harder than I expected, why do people say this class is easy,” reads another.

Earth as a Planet is taught in a lecture format three times a week. Attendance is not recorded, nor is there a discussion or lab aspect to the course. Like many other Core classes, the syllabus includes weekly homework assignments, quizzes, and a final exam at the end of the quarter.

But one assignment embodies Earth as a Planet’s controversial reputation better than any other: the moon journal. Throughout the quarter, students are expected to make 15 unique observations of the moon. Each observation needs to include a sketch or photograph of the moon and details such as the moon’s angle of elevation, its direction, and the location of observation.

The vast majority of course reviews praise the assignment for being a fun demonstration of the material learned in class or describe it as an easy element of the course. But despite its relatively simple nature, a number of students fabricate journal entries.

“I’ve always known [using online resources instead of observations] is something that students have been doing. But, in the end, the goal is for them to be able to demonstrate that they understand why…we see the changes in the moon that we do see,” Ciesla told The Maroon in an interview.

Ciesla began permitting data from online sources to substitute for moon journal observations during the COVID-19 pandemic, when some remote students complained that they were unable to make observations because of quarantine restrictions.

The use of online resources by students continued without issue until autumn quarter 2022, when some students submitted observations that were scientifically impossible to record.

“One of the issues was there were some students who submitted things last year that just were nonsensical. They said, ‘I saw the moon at this time, and it was below the horizon,’ which is just physically impossible and demonstrated that [they] didn’t understand a lot of what we discussed in class.”

Despite the clear evidence of wrongdoing, multiple students refused to admit their mistakes, leading Ciesla to report them to the dean’s office.

“’I’m not here to investigate things,” he said. “I’m just reporting what I see, so if the student did something, then there should be some investigation here. I contacted the dean’s office and told them what had happened. That made us more aware this year of things to look out for.”

However, last year’s students were not the only ones responsible for Ciesla’s renewed focus on academic integrity. A spate of cheating on a series of homework assignments from before Thanksgiving break had made it clear that academic integrity was an issue in the course. Upon reviewing the moon journals after they were submitted on November 27, Ciesla found many more academic integrity violations.

In the November 30 email, Ciesla wrote that he and his teaching assistants were compiling a list of students who were suspected to have used online resources and who would be referred to the Dean of Students. Students were also given the option to confess if they had fabricated observations, “in which case the penalty [could] be lessened.” The deadline for confessing to cheating would be 11:30 a.m. on Friday, December 1—the start of the next lecture. According to the email, moon journal grades for the entire class would be delayed as a result of the suspected violations.

“Given that the final was just in a matter of days, it was important for the students to know that academic integrity issues are taken seriously,” Ciesla said. “That’s what led to [this] kind of communication.”

Within minutes, posts about the email began to appear on the anonymous social media platform Sidechat, which maintains school-specific communities that can only be accessed by verifying that one has a university-affiliated email.

The case, dubbed “Moongate” by students, went viral on campus as students commiserated, joked, and shared information about the case.

The circulation of the moon journal case on social media led to an influx of emails from students to the Student Advocate’s Office (SAO), a branch of Undergraduate Student Government tasked with advising students who are “navigating administrative and disciplinary procedures within the College, including housing, academic, and financial aid proceedings.”

Even more students reached out after the office posted graphics about the situation to social media and placed placards in front of Kent Laboratory 107, the classroom where Earth as a Planet lectures were delivered.

Third-year Amadis Davis, SAO’s lead caseworker, served as the primary point of contact for students accused of cheating.

“As time passes, we’re seeing more and more people reach out, presumably because word of mouth has spread. But we’d like to help as many students as we can,” Davis told The Maroon in an interview before the resolution of Moongate. “I would really caution against thinking this is less serious because the matter is called a moon journal. I do understand there’s a certain amount of it that might sound silly. However, in terms of the way it’s viewed, it’s still an assignment that you have committed academic dishonesty on if you [cheated].

Ahead of the Friday morning deadline, numerous users on social media purported to have confessed. Others declared that they were determined to fight any accusations, often using the slang term “standing on business” or an alternative version, “standing on bidness.” Both phrases, while dependent on context, convey that a person is either standing their ground or focusing on their work.

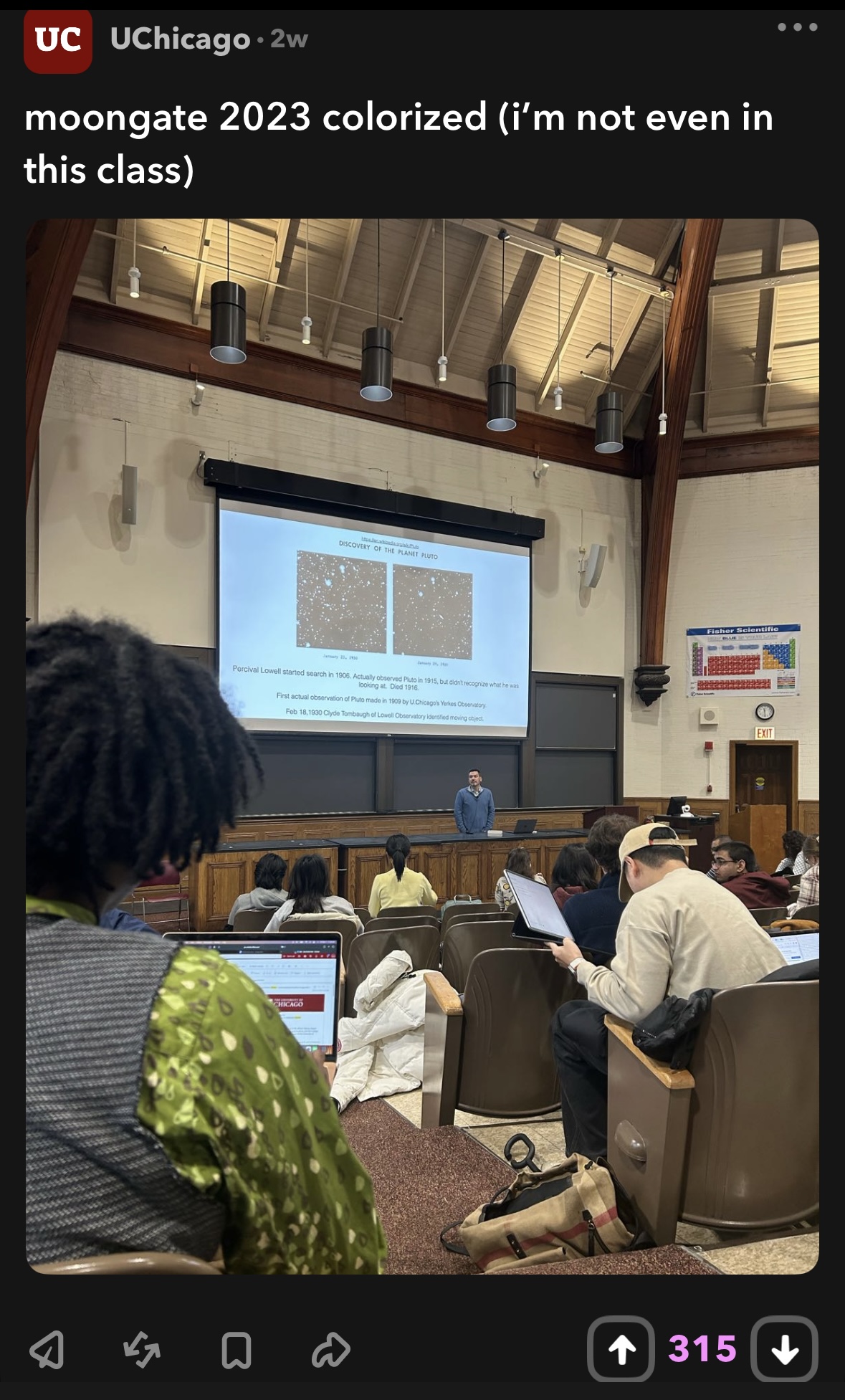

Friday’s class, the final one of autumn quarter, had record attendance, according to those present. There were few seats left in Kent Chemical Laboratory room 107, where the class was held, as students not enrolled in the course attended to hear additional details about “Moongate.”

Ciesla spent most of the class delivering a lesson on Pluto. When he finally addressed the moon journal at the end, he said that students who confessed would probably not receive a punishment but that if they didn’t confess and had been suspected of cheating, their cases would be transferred to the Office of the Dean of Students.

At one point during the final lecture, Ciesla read the Walt Whitman poem “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” a tradition he has maintained at the end of every quarter.

On December 3, students enrolled in the course received a second email titled “Moon Journal Resolution.”

The email said students who were not suspected of misconduct would be graded as described in the syllabus—the moon journal would account for 20 percent of their grade. To make up for the increased scrutiny and subsequently lower grades on the moon journal, students could have their grade on the moon journal replaced by their score on the final if it benefited them, which would make it worth 50 percent of their grade.

Students who had admitted to fabricating entries would not face disciplinary action and would instead have their moon journal grades substituted for their grades on the final, automatically making the final worth half of their overall grade.

“For those students who self-reported…we cannot count your journal towards your grade. However, we also recognize and appreciate the courage that it took to self-report, and we want to acknowledge that. None of you will be referred to the Dean of Students office,” the email read.

Students who were suspected of academic dishonesty and did not self-report would be referred to the Dean of Students office for investigation. If it was determined that a violation occurred, then they would receive a zero on their moon journal assignment and their final grade would be capped at a C.

The subject line of this email, however, belied the sense of uncertainty some students faced. In particular, students who had fabricated entries and chose not to confess as well as students who had submitted legitimate entries but were afraid of being mistakenly accused of cheating remained unsure of their fates.

In particular, there was widespread confusion around the University’s academic disciplinary system, which varies depending on a student’s academic history, year, and the course. While details about the discipline process and the outcomes of past cases can be found on a page maintained by the Office of College Community Standards, students have limited information for gauging the severity of their cases or estimating potential penalties.

“Every single year they publish what the charge was and what the result was of some of the cases that they see without any specific details. And so I find that it can be incredibly difficult for students to get a bearing of what their case is. The charge might be three counts of academic dishonesty, and the reported result is nothing happens. But it’s dependent on circumstance,” Davis said.

The clearest statement of what students can expect in terms of punishment can be found on a page on the website of the Office of the Provost.

“Instructors have a range of options in dealing with academic dishonesty. It is within the discretion of the instructor to use evidence of plagiarism or academic dishonesty as grounds for failing the student in all or part of the course. The area dean of students may be asked to speak with the student to issue a formal warning or to consider disciplinary action,” the page reads.

“Anything you know about law or due process, presumed innocent, or innocent until proven guilty, none of that really applies here,” Davis said. “The College has its own policies; it has its own rules. The letter of the law is the syllabus of the class and the student handbook, so I think that’s a common misconception that it’s innocent until proven guilty.”

Five days later—December 8, the final day of autumn quarter finals week—clarity came in the form of an email titled “Earth as a Planet Update: Final Exam Grades and Final Grade Resolutions.” Students were informed that if they had not received an email letting them know they were suspected of cheating, their moon journal had not been flagged as fabricated.

“I had no interest in making an example of anybody or making this a big deal. When something happens, if students are recognized as doing something wrong, they take responsibility for it and use it as a learning exercise, and then you move on from it,” Ciesla said. “That’s what I wanted to achieve in most of the cases, and that’s why I gave students that option.”

Throughout and after Moongate, some students expressed frustration at what they believed to be a lack of clear communication.

“I think it’s a very light case of cheating, especially considering that every single other year, people have cheated on this assignment,” said a third-year student who fabricated entries and did not confess and spoke on the condition of anonymity. “If they would have made it more clear or emphasized that they were taking academic integrity very seriously this year, then it would have been more digestible. But because they didn’t do that, it’s more shocking and feels kind of like a waste of time.”

Other students thought there was a clear basis for the accusations.

“Because he stated so clearly at the beginning of the quarter that this is a fairly simple assignment and ‘here’s what’s expected of you’ and we really want you to learn and do this in real life, then yeah, if you cheat and go online and do it in a day, it’s fine to get your points reduced because there was a standard set,” said Jules Yaeger, a third-year enrolled in the class whose journal was not flagged for cheating. “If he had pulled that out of nowhere, it would be like, ‘Whoa,’ but no, it was in the syllabus.”

Still, even students like Yaeger who sympathized with Ciesla reported that the nature of the email was unnerving.

“I know many people were freaked out. I know people who didn’t cheat, myself included, and we were still freaked out anyway, just because he dealt with it seriously and formally,” Yaeger said.

According to Ciesla, his experience last autumn of having students who refused to admit to cheating despite clear evidence prompted him to take stricter action. “You might ask why not just lower the grade there. But in part it’s because of this back and forth that I had with students in the previous year.”

Despite the drama of Moongate, many students still enjoyed Ciesla’s class.

“I think he’s just really passionate, and I’ve had several really good science Core professors, people who obviously are teaching something they’re interested in and are doing a good deed of taking up the Core class slack. And they still try to make it engaging and don’t lose their passion for it, which I really, really respect,” Yaeger said. “Weirdly enough, this Sidechat thing made [Moongate] have more hype, but I think it also sort of alleviated a little bit of tension because it was a joke. I know people personally that were worried about it and were able to find some humor in it.”

As for Ciesla, next year will be the first in which he does not teach Earth as a Planet.

“This was something I had decided before this [cheating scandal],” he said. “Having taught it since 2015, I’m ready to try something a little bit different.”

Katherine Weaver and Finn Hartnett contributed reporting.

bob / Jan 12, 2024 at 1:31 pm

“I think it’s a very light case of cheating, especially considering that every single other year, people have cheated on this assignment,” said a third-year student who fabricated entries and did not confess and spoke on the condition of anonymity. “If they would have made it more clear or emphasized that they were taking academic integrity very seriously this year, then it would have been more digestible. But because they didn’t do that, it’s more shocking and feels kind of like a waste of time.”

lol? you needed to be told you can’t cheat?