The University “where fun goes to die” seemingly defies its reputation.

1

A Friday night. A familiar scene unfolds. A vast house, its exterior decaying, yet alive with a buzz of youthful energy. The thumping bass of a mid-2010s pop playlist seeps out into the yard.

In the basement, a game of beer pong plays out, a competition so fierce it might be game seven of the finals. Above, a bomb site resembling a kitchen, the countertop a graveyard of empty cans and cartons, while in the corner a lone soul concocts a drink so strong it could strip paint.

Crowds pulse in and out of dimly lit rooms, laughter ringing over the crinkle of red solo cups. Odors of cheap beer mingle with juvenile desperation and misplaced promise. The air is a cocktail of inebriation and exhilaration. The night is messy, loud, and utterly unforgettable.

Here, social hierarchies bubble like a pan sauce, reducing in alcohol and patriarchal bravado.

Amidst the laughter, spilled drinks, and sprawled bodies, you realize, for all its absurdity, this chaotic, uniquely American ideal of fun is alive and well at the University of Chicago.

Fraternities, mysteriously absent from official University messaging, are a staple of the social scene on campus. These exclusive all-male societies have historically had a troubled relationship with the press, appearing in headlines alleging misconduct, depicting them as housing racists, sexists, and rapists.

As a straight-passing man, I have had candid insights into these male-dominated spaces; some members suppose I’m “one of them,” and others are willing to break vows of secrecy to share their experiences.

In the fall, the campus blooms with bizarre fashion choices. In lecture halls, seminars, and on the quad, fresh-faced first-years don suits and ties, Playboy Bunny lingerie ensembles, chicken costumes, and, my personal favorite, paddles of Perry the Platypus onesies.

According to fraternal edicts, new members look after items at all times. My statistics classmate once kicked open the door to a lecture hall 15 minutes late wheeling in a mop and bucket. Another in my Classics seminar thumped a cinder block onto his desk, unbuttoning his blazer before sitting down. At the scattered laughter, he muttered, “Pledging.”

Pledging is a secretive fraternal initiation process, also defined as “a binding promise.” Some carry that commitment in memory. A man I spoke to, and many others, carry it in scar tissue.

2

“It was completely consensual,” A.—a former member of a fraternity on campus, identified by a pseudonym to protect his anonymity—recounted, laughing. He described the ritual to me as a joke between brothers.

A metal coat hanger, twisted into a Greek letter, heated in a cast-iron pan slick with olive oil. The press of searing metal against skin. The sharp sizzle, the stench of burnt flesh.

M.D., a first-year fraternity brother with whom I also spoke anonymously, described the branding as, “Fucking nasty. When my buddy showed me, it was literally his entire fucking ass cheek with the logo on it, and it doesn’t go away. That is incredibly dehumanizing.”

A. chuckled. “I don’t really think about it unless I’m telling this story, because it’s, in my opinion, funny.” A coat hanger branding, a permanent scar—somehow, a punchline. The absurdity would almost be amusing, if it weren’t so revealing. Although he was branded with a coat hanger, his lighthearted recollection of the “bonding” he felt during the pledging process felt simultaneously familiar and perplexing.

Other than branding, some fraternities also have assigned tasks attached to pledgeship. Pledges’ completion of tasks impacts their bids in joining the fraternity. M.D. explained: “Pledge tasks are pretty ubiquitous things at any school. The ones here are not egregious for the most part.”

M.D. went on to give an example of a pledge task on campus: “A nicotine pledge. You just carry nicotine at all times. Frat X has eight of them, I think. You carry Zyn [pouches], vapes, cigarettes, whatever the brothers request. You make deliveries. If someone calls you like, ‘Yo, can I get a cigarette?’ You got to run across campus and go see them. You might miss class. It sucks.”

Why do fraternities require such arduous, embarrassing hazing? “[You’re] being forced to wear ridiculous stuff around campus, you’re getting yelled at together,” A. said in warm nostalgia. “You’re doing all this dumb stuff together. I think you do grow closer in that time.”

Though I have personally never pledged to be in a fraternity, the trials and tribulations one undergoes to become part of a patriarchal in-group—a space perpetuating traditional gender roles by prioritizing male authority—are not beyond me.

One might say that I have been hazed before. That is not what it was called, of course. My rugby team called it bonding. My military called it training. My firefighting academy called it conditioning. The logic is the same: the forging of loyalty through suffering, the consolidation of power through pain.

Much like the fraternity men I interviewed, my quests of worthiness were far from pleasant, but I recall these memories perhaps more fondly than I should. My experiences speak to an insidious narrative within masculinity: it teaches one should be grateful for their suffering.

Fraternity hazing is different. Where military rites at least claim to be in service of an external good—defense, survival, discipline—fraternity hazing is recursive. The trials and tribulations of pledging seem to be self-sustaining and artificially manufactured.

As A. said, “Trauma bonding, that’s all it is, right? It’s just light hazing.” A. admitted that apparently the “light hazing” of coat hanger branding, verbal abuse, and public embarrassment exist for the sake of bonding brothers.

M.D. imparted a similar sentiment: “Yes, it’s a quarter of ‘I’m this guy’s bitch.’ Whatever, I have to do some gross shit. Oh, I have to drink, but it’s nothing. It’s not fucking World War III, like, there are schools where it is quite literally hell on earth.”

A. frankly reflected on the issue, “That’s just the nature of pledging, right? There’s a power dynamic, it’s reinforced.” The Stanford prison experiment–esque power dynamics present in the pledging of new fraternity brothers highlight another cultural aspect that dominates one’s attention: the unavoidable stench of testosterone and masculinity.

Hazing in fraternities, much like any other ritual of initiation in a patriarchal group, creates and reinforces the fraternity’s internal logic, as A. said: “With any kind of hazing ritual, there is a sense [of] ‘I went through this. I’m on the other side. Now, I’m gonna have some fun.’”

Psychologists write about fraternity hazing as a deeply embedded part of the social fabric of college, one that furthers itself through a cycle of conformity, and submission. It is a ritual that demands submission to a perpetuation of domineering masculinity.

My two sources were quick to remind me that, in the grand scheme of fraternity hazing, UChicago is nothing compared to schools with more intense fraternity culture. M.D. claimed, “Frat hazing in Chicago, maybe you think it’s not great, but keep in mind, this is the most watered-down hazing possibly in the entire country.”

But “watered-down” or not, the logic remains the same. The bond of suffering is foundational for the next cycle of hazees. Members are initiated into the same violence that “proved” predecessors as worthy of brotherhood, manhood, and belonging.

3

Despite the tribulations, young men remain drawn to fraternities for the brotherhood, lifelong friendships, and community. The majority of fraternity brothers, much like the rest of the student body, are in their first years of adulthood at an academically brutal university—that is, just trying to find their community.

Men may be particularly vulnerable to loneliness and the mental illness that follows. The harmful effects of traditional masculinity lead to loneliness and isolation. Myths of masculinity prevent men from being emotionally available to others and themselves, and one must dismantle these notions to free men from loneliness.

I know firsthand the outdated expectations of masculinity, internalized from society, that, simply put, “boys don’t cry.” These masculine expectations set forth by societal norms of being stoic, emotionless, and providing, are insidious obstacles to the vulnerability required in the male quest for belonging and community.

I find myself in the trenches alongside the men fighting a silent, increasingly uphill battle against loneliness and mental illness. One finds an irreplaceable community through brotherhood. Can anyone fault men looking for a sense of belonging?

Though the importance of community is not lost on me—I, myself, have found solace in the friendships derived from other forms of brotherhood—the question remains: What makes fraternities stand out from other groups? Why not look for a community somewhere less controversial?

The answer lies in these societies’ unique ability to provide access to alcohol, or as A. frankly stated, “It was a place to drink on the weekends and friends to hang out with.”

M.D. furthered this sentiment, admitting, “If you’re under 21, it’s hard to be super social, extroverted, and go out as a guy if you’re not a fraternity, unless you have the world’s greatest fake ID and a group of friends that always want to go out.”

America remains a country where the majority of university students are not above the legal drinking age. For these undergraduates—full-time students and part-time underage drinkers—the fraternity house is their only option for an alcoholic third space. That is, at least, until they move off campus or find other means.

In the holy halls of the fraternity house, alcohol is the great emancipator. Within these underaged drinking cathedrals, cheap beer flows as holy water, acting as both the congregation’s lubricant and its sanctifying agent.

M.D., having previously worked as a sober monitor at his fraternity house, recalled the scenes vividly: “I literally have had to walk around in a yellow vest at parties, like, ‘Oh, my God, this girl’s passed out.’ I can’t tell you how many times that happened.”

The comical proportions of American fraternity drinking are a collegiate liberation from an alcoholically oppressive society imposing a ludicrous legal drinking age, a relic of a bygone era. Fraternities don’t just normalize binge drinking—they industrialize it. A 2018 study found that by age 35, nearly half of former frat members show signs of alcoholism.

A. admitted he barely remembers the night he was branded: “Oh yeah, I was shit-faced.” A moment of permanent scarring, blurred by intoxication—like many things in frat culture, a ritual sustained by alcohol and amnesia.

The process of fraternal drinking, much like hazing itself, is not merely about pleasure or camaraderie. This coupling is a performance, caricaturing drunken masculinity, enacted not just for the self, but—in more ways than one—supplied for an audience that insists upon it.

The fraternal combination of alcohol and patriarchal culture, an American collegiate staple, creates risks that go beyond what one encounters elsewhere. Caitlin Flanagan emphasizes this criticism in her essay for The Atlantic, “The Dark Power of Fraternities,” claiming fraternities outpace commercial spaces in harm, especially as a result of the absence of responsible oversight.

As M.D. conceded, “You’re less likely to get raped [or] roofied at a bar than you are at a fraternity. Maybe that’s a reflection on how fraternities throw parties. At a fraternity, the likelihood of being raped is exponentially higher because that’s where everyone goes out.”

Flanagan criticises the current fraternity model, arguing that frat brothers are tasked with enforcing national rules they have no interest in upholding. She argues that the national guidelines for permitted practices, sober checkpoints, and guest lists read as a bureaucratic satire—impossibly detailed yet laughably ineffective.

4

Though fraternities refuse to follow national chapter rules, they are not lawless spaces. They are instead governed by entrenched patriarchal values.

Lucia Roure, a first-year and sorority sister of Alpha Omicron Pi, described it as such: “Frat culture as a whole, there’s something to be said about [women] being viewed as an opportunity. What I mean by opportunity [is] if there are more girls, you’re probably [at] better odds of hooking up with one.”

The notion of the “ratio” in American fraternities—a numbered balance between men and women at social events—reveals broader societal dynamics surrounding gender, power, and objectification. At these events, fraternities impose the belief that having more women increases the event’s success.

As second-year Attila Newey describes: “Frat parties are designed for people to hook up, people are making out everywhere. It’s kind of foul. You’re all very close together. It’s dark, everyone’s drinking. The ratio is a symptom of that, assuming that the majority of [the fraternity’s] brothers are straight, and you’re prioritizing their interests, then you want less competition in a wider pool. This feels [like] very objectifying underlying thinking.”

Newey’s take might seem exaggerated, but it captures an uncomfortable truth: “The ratio” isn’t just party logistics. It is a fraternal economy where women’s presence is currency, traded to maximize male pleasure. It’s a system where desirability is quantified, where access is controlled, where the unspoken male logic remains: more women, less competition, better odds.

During a peer review session on Aristotle—because, of course, this is still UChicago—I mentioned to a friend of mine that I was writing about fraternities and was curious about her experiences. She told me of a system she had learned to guarantee entry to frat parties, despite “the ratio.”

She described how, while en route to “fratting,” she and her female friends were in the habit of taking off their jackets, pulling down their shirts, and throwing their hands over the men in their friend group, as though they were together.

The combination of cleavage and commitment to companionship would make the pledge at the door more likely to let the whole group in, rather than just the women, she explained. In a moment of vulnerability and self-reflection, she said it in plain English: “I feel so icky partaking in my own objectification.”

This feeling of discomfort with one’s commodification encapsulates what is so insidious about “the ratio” in frat culture. As bell hooks argues in The Will to Change: “We need to highlight the role women play in perpetuating and sustaining patriarchal culture so that we will recognise patriarchy as a system women and men support equally, even if men receive more rewards from that system.”

5

“The ratio” is a fraternal calculus of patriarchal power where female presence is commodified to reinforce gendered power structures. When one is told that there needs to be a certain number of women relative to men, it does not simply mean more women are invited to participate.

In “Why Is Fraternity Membership Associated With Sexual Assault?”, Seabrook et al. conclude: “The pressure men feel to uphold masculine norms, their endorsement of these norms, and their acceptance of objectification of women help explain why fraternity members are more accepting of sexual violence.”

This objectification entrenches traditional gender roles where men are active—controlling the party, space, and rules—and women are passive, their worth defined by their enhancement of the male experience. Even if fraternity members don’t consciously view women this way, “the ratio” surely influences their interactions with women in these spaces and beyond.

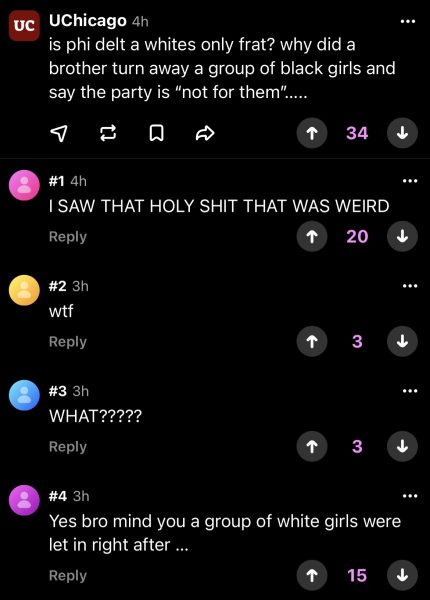

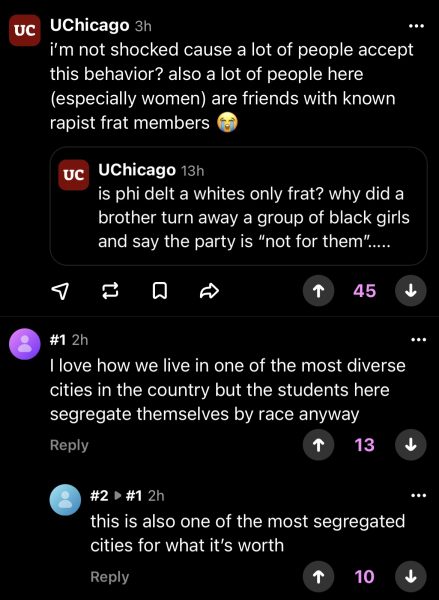

While “the ratio” may seem like a simple calculation, it operates within a broader racial and cultural matrix where women of color, non-cisgender, or non-heterosexual women are often hypersexualized, exoticized, or excluded entirely. Any critique that overlooks these intersections risks overlooking the complexity of the issue.

Gender, race, and sexuality intertwine to create unspoken social hierarchies of desirability. Sociologist Katherine Cross elaborates:

“To some white men, Asian women top their hierarchies of desirability. But what do those women get out of that? Suffocating stereotypes of docility; discrimination; abuse… These hierarchies of desirability determine your value to people in positions of relative power and privilege. Thus, even being at the top isn’t a guarantee of good treatment. It just makes you the prime cut of meat.”

“The ratio” reveals a plague of patriarchy that treats women’s bodies as sites of male enjoyment, an illness that collegiate culture is all too ready to expose our youngest and most vulnerable to. There is a particular danger, as Roure said, “especially when you’re younger, looking for validation from an older [fraternity] brother.”

“The ratio” poses a challenge for men, too. It is a Herculean task for a non-affiliated man to enter a frat party. In 2024, Newey starred in the YouTube video “How to get into ANY Frat party,” which has accumulated over 24,000 views. In an interview with the Maroon, Newey summarized what men face: “There’s a bunch of pledges on the door. You just have to do these ridiculous things to try and get in, or know multiple brothers.”

Newey’s video asks: If men can’t get into a frat party but women can, what if a man dressed up as a woman? At 6’3″, Newey’s goal of blending in with his entourage of female conspirators was no easy feat.

On camera, he shaves his armpits, is embellished with fake eyebrows and eyelashes, dons a bald cap and a blonde wig, purchases an XXL sports bra, fills it with water balloons, then applies the finishing touches of contouring makeup and an off-the-shoulder top to complete the look.

Beyond his brief labor of conformity to feminine beauty standards, video production research meant that Newey had become a bona fide expert on the fraternity subculture. According to his interviewees, denial of entry to fraternity parties had nothing to do with the heteronormative elimination of competition driven by misogynistic thinking.

Allegedly, the denials of entry relate to the possibility a partygoer commits sexual assault. He said: “They don’t want to be liable for men making bad decisions at the parties, but I don’t know. Cases [such as in the video] where ‘if you fight over this pothole, you can get in.’ That doesn’t test if [a man is] going to sexually assault someone. Those two things do not correlate!”

A more intriguing aspect of Newey’s project was the choice of fraternity to infiltrate—Delta Upsilon, which, following a string of controversies, is now known as Iron Key Society.

6

Iron Key Society (formerly Delta Upsilon) is best described as Schrödinger’s frat. It is both dead and alive; it is a frat and isn’t. Until one revisits the past, it remains a paradox.

Delta Upsilon (DU) appeared in a 2012 article titled “Fraternal failings,” in which the Maroon wrote, “[They] created a public Facebook event for a party titled ‘Conquistadors and Aztec Hoes.’”

It gets worse. DU, in their response letter, wrote, “It was never our intention to offend or hurt any minority groups.” Yet, the event description asked partygoers to bring out “an unlimited need to conquer, spread disease, and enslave natives.”

As the 2012 Maroon Editorial Board wrote, “Some might claim that such incidents are not malicious, but are exaggerated or done in irony and jest; however, no matter their intended effect, they just come across as stupid.”

As if the “Aztec hoes” debacle wasn’t enough, in 2018 DU faced allegations of drugging students with Xanax. Nothing screams their code of “Character, Culture, and Justice” quite like roofies.

The same Maroon article reported: “When contacted by phone… the president of DU at UChicago would not comment on the allegations and referred the Maroon back to the international organization. When asked why the chapter didn’t report the allegations to the international organization, [the president of DU] said, ‘I’m going to go now’ and hung up the phone.”

Then came the 2018 DU Sex Position Quizlet, a set of flashcards leaked of DU brothers’ favorite sex positions, including “punishment” and “as long as I’m in a bootyhole,” along with other more disturbing items. “The representatives did not address whether winter pledges were asked to memorize the document as a hazing assignment,” wrote the Maroon.

Not long after, the Chicago Police Department investigated a report of sexual assault in DU’s fraternity house. As of 2019, the investigation remains open.

In 2022 came the article “Delta Upsilon Fraternity Charter Revoked.” The international chapter board explained its decision in its letter to chapter alumni. “‘For more than five years, the chapter has not met the expectations set forth in the Fraternity’s Men of Merit Chapter Standards Program.’” The Maroon elaborates, “The Chicago chapter had accumulated more than $60,000 in debt… and had been the subject of multiple hazing complaints.”

What power did the international chapter have at all? As Newey highlighted in our interview, “there are things even that [frat brothers] are like, ‘National chapters can’t find out about [that].’ There’s a disconnect between what happens on campus and who the frats report to.”

Liabilities such as debt, hazing, racist public relations, drugging allegations, and sexual assault allegations meant that DU was kicked out of a international fraternity chapter and had to reinvent itself. Alternatively, “the brotherhood which existed as Delta Upsilon reorganized itself back [sic] to The Order of the Iron Key.”

Enter the reborn Iron Key Society. Schrödinger’s frat: still a frat, but not. The “frat,” detached from the international chapter, is no longer held to international guidelines. How the new organization holds itself accountable remains unclear, but its new Sexual Misconduct Policy is lackluster at best.

In a 2023 Thanksgiving article “What We’re Thankful For,” the Maroon Editorial Board expressed gratitude for the following: “Iron Key Society, for teaching us how real phoenixes rise from the ashes—even when they really shouldn’t.”

This case study confronts the reality of what is overlooked in the name of tradition or community. Though, as anyone with a shred of ethical consideration will tell you regarding Schrödinger’s cat and frat alike, the whole experiment should have been euthanized years ago.

7

When I asked A. about the relationship between fraternities and sexual assault, he admitted, “Fraternities are known for supplying alcohol to underage students at events. I’m not gonna bullshit. Of course it happens.”

A 2017 Maroon article, “UChicago Greek Life,” reported, “UChicago’s fraternities banded together to create the Fraternities Committed to Safety (FCS) policy… ‘a baseline of procedures aimed at preventing incidents of sexual violence.’ All 10 fraternities signed the document initially. However, members of the Phoenix Survivors Alliance have reported violations of the FCS policy by several fraternities.”

It’s worth noting that the FCS policy was signed in 2017—just a year before DU made headlines. In 2018, a fraternity brother was expelled a week before graduation for “verbally abus[ing] and sexually assault[ing] a female student.” The trend continued in 2019, when sororities suspended events with a fraternity, citing reports of “date-rape drugs.”

Is prevention a problem of implementation or neglect? Despite being a brother formerly in a leadership position, A. said, “I’m sure procedures have been written up, but again, I was never privy to them.”

Why does the University itself not take action against the harm these fraternities cause? Flanagan argues fraternities provide off-campus spaces where underage drinking can happen, and where liability is outsourced. When the inevitable scandals occur—instances of hazing and violence—the University can respond somewhat predictably, with plausible deniability.

Not recognizing fraternities is not a moral stance. It is a legal maneuver. The University is “unaffiliated” with Greek life, and thus remains silent. Silence, we know, is rarely neutral.

In 2016, former Dean of the College John Boyer acknowledged the simple fact that many of the University’s biggest donors were fraternity alumni: “A lot of alumni leaders that I know were part of Greek life, they feel very strongly and protective of that. That’s undeniable.”

It is an open secret that Greek life produces financiers, and financiers fund universities. Byron Trott (A.B. ’81, M.B.A. ’82), a former Goldman Sachs vice chairman, was a fraternity man. So was UBS Wealth Management’s Bernard DelGiorno (A.B. ’54, A.B. ’55, M.B.A. ’55). Harold “Jeff” Metcalf (A.M. ’52), whose name adorns the University’s prestigious internship program, was a fraternity man.

The University claims not to recognize fraternities yet benefits from them. The fraternity brother who commits sexual assault today may be the donor who funds a new building tomorrow. The administration has, one imagines, made its peace with this compromise.

This is not a failure of policy. It is policy. The University of Chicago, like all elite institutions, has mastered the art of selective ignorance. It knows what it must know and unknow depending on convenience. Fraternities continue to brand their members, haze their pledges, assault their guests. The University continues, pretending with perfect sincerity, to be surprised.

8

Who considers the fraternal history of hazing, misconduct, and toxic masculinity, and says, “This is the brotherhood I’ve been searching for?”

Despite the extensive research that exists on the danger frats pose, they are permitted as unchangeable—a collegiate cultural staple. Fraternities exist persistently because they are a place where problematic practices of masculinity among brothers thrive and persist unapologetically.

The stereotypical archetype of a fraternity brother is akin to those that philosopher Amia Srinivasan describes in her sardonically titled feminist essay, “The Conspiracy Against Men”:

“These disgraced but loved, ruined but rich, never to be employed again until they are employed again, prodigal sons of MeToo: they and their defenders are not outraged by the falsity of women’s accusations. They are outraged by the truth of those accusations. They are outraged, most of all, that saying sorry doesn’t make it all better: that women expect them, together with the world that brought them to power, to change. But why should they? Don’t you know who the fuck they are?”

Perhaps fraternities are not all monoliths of misconduct. As do other organizations, each fraternity has a different type of branding, values, and members. M.D. said, “Fraternities, by nature, attract different kids and have different pledgeships and have very different characters in them, and ultimately, have very different problems, some much bigger than others.”

Perhaps this is true. I’d like to imagine a world where Iron Key Society makes their members memorize feminist literature as opposed to a Quizlet of their brothers’ favorite sex positions. Until then, it would be best to accept that fraternities will continue denying responsibility and offloading it to others, crying “not all fraternities,” reminiscent of how men are quick to say “not all men.”

Yet, one does find “far too many women.”

I recall my source’s “consensual” branding, the irony of his words painstakingly obvious. Unlike fraternity brothers who willingly receive a coat hanger oil burn scar on their ass or endure other hazing, not everyone subject to the power dynamics present at a fraternity has the privilege of deeming their experiences as “consensual.”

Just how unavoidable is the relationship between fraternities and sexual misconduct?

A 2007 study in the Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice found that first-year college men affiliated with fraternities were 3.2 times more likely to commit sexual assault. This was the third study to replicate such findings.

Do fraternities select for rapists? It appears they instead create them. According to a 2020 analysis in Violence Against Women, “It was not men who had a prior history of sexual violence who gravitated toward fraternities. It appeared to be the fraternity culture itself that was responsible for a threefold increase in rape among fraternity men.”

A 2020 Maroon article, “Tracking Title IX,” investigated the relationship between fraternities and sexual violence across 33 universities. It concludes, “The two schools with no Greek life on campus reported the lowest rates of sexual assault.”

A 2019 study by the Association of American Universities (AAU) on the University of Chicago found that for undergraduate women, 39.4% of all non-consensual “sexual touching” occurred within a fraternity house.

The same study found that 30.0 percent of women reported some type of nonconsensual sexual contact. This is contrasted with the national average of 26.4%. Though the national average is outrageously high, it makes one wonder what makes the sexual assault rates of the University of Chicago fall 3.6% above it.

These findings may demonstrate how a trend of sexual assault at the Univeristy of Chicago runs beyond fraternities. In “A Special Problem,” the Maroon dove into the University’s long-standing issues with sexual assault, linking current trends to a dark history. The authors of the piece interviewed alum Christine Fair (S.B. ’91, A.M. ’97, Ph.D. ’04).

“Now an associate professor at Georgetown University, Fair has come to realize that her experiences at the University of Chicago were unique to the school. ‘Chicago sticks out as a real distinctive exception in terms of the hostile environment particularly for women… It is not cost-free to call these bastards out on their bastardry.’”

In “Something’s Rotten,” Sarah Zimmerman (A.B. ’17) wrote on the future of campus frat culture: “Banning all fraternities is a long-shot, especially on a campus with an administration as infamously reluctant as our own. There are undoubtedly upstanding members of campus fraternities… Unfortunately, these good apples still belong to a rotten tree; ultimately, such a tree needs to be cut down before it can do any more damage.”

One cannot expect a rotten tree to axe itself, though there may still be a path forward, a path that necessitates transformation from within. As the University is reluctant to take decisive action, the responsibility for meaningful change may rest with the fraternities themselves. Fraternity members must begin confronting the problems within their own organizations.

9

For many, fraternal brotherhoods promise to mend the patriarchal predicament of loneliness. Fraternities have an undeniably close-knit culture, a community that members know, as A. said, “has our back no matter what.”

Do all fraternity brothers have each other’s back no matter what? Are brothers willing to overlook anything, just because the brotherhood has been through everything together?

Correcting unacceptable behavior is difficult. After all, we men risk upsetting the community we have quested so hard for. I’ve personally paid the price of losing friendships after learning of unacceptable behavior. In those instances, I had to ask myself: if a community tolerates unacceptable behavior, is that a community worth keeping?

The myths of masculinity born of patriarchy are what render the male quest for a community such a dire one. Patriarchy limits men. It narrows our emotional range. It suppresses vulnerability. It distorts our relationships. It takes a mental toll.

Feminism is not a movement for women alone; it is for the liberation of everyone from the shackles of patriarchy. Men especially benefit from patriarchy, thus we must take responsibility for dismantling it.

The same power dynamics that enforce problematic ideas can serve to self-regulate for growth. This isn’t about grand gestures or heroic acts—it is about the persistent effort to challenge the culture one influences, leveraging privilege to confront the toxic masculinity that perpetuates patriarchy.

I know firsthand this call for accountability is not just theory but praxis.

During my time as a lieutenant in fire and rescue , through vehemently correcting moments of misogyny, my colleagues and I made clear that such behavior was unacceptable in a culture we influenced—no exceptions. This example wasn’t about being a “perfect ally” or waving a flag of moral superiority but about doing the uncomfortable work of reconditioning those around you.

Those who care should positively weaponize reinforcement and power dynamics to fashion meaningful change. If positive results can happen with conscripts, university students can certainly grow too. It’s about staying to work on cultures where change is possible, even if that means navigating discomfort and resistance.

Change doesn’t happen overnight but through consistent, thoughtful action.

If we men—fraternity brothers, classmates, and friends—can hold each other accountable, we will begin unraveling the deeply ingrained systems of patriarchy that govern so many of our spaces and relationships. That is where the real work begins against misogynistic indoctrination.

Misogyny requires indoctrination. Men, born to mothers, do not naturally hate women—rather, they internalize misogynistic values throughout their lives. To fight misogyny is to fight the culture of indoctrination that exists for men and women alike, wherever it may be found, through the disruption of misogynistic echo chambers.

Misogyny is not an instinct. It is an education. For many, fraternities provide it.

To examine the American ideal of fraternity fun is to uncover an unavoidable truth: like the nation itself, this fun is made for a particular kind of person. The kind already accustomed to being centered—privileged, overrepresented, infantilized, spared from consequences.

Even in cases as clear-cut as People v. Turner, society turns to shield a “promising” young man. But where is its commitment to protecting promising young women?

Fraternities endure as cultural fixtures, offering men community and students alcohol. But these offerings come at a cost: the systematic indoctrination of misogyny. This is not incidental. It is a key transaction, one that all must reject.

Fraternities and the student body alike must renounce not just a certain kind of fraternity, but a certain kind of man—the one raised for entitlement, shaped by a grotesquely outdated masculinity, and emboldened by the injustices it permits.

Yet, many will trade their convictions for access to a space where underage liquor flows, as if the tuition for all-American college experience is paid for in moral compromise.

After all, what’s manifesting misogyny when the lukewarm beer is free?

10

It’s the fall quarter. The most solemn undertaking is about to begin. A fraternal branding ceremony is underway. A coat hanger bent into a Greek letter. Olive oil inside the cast-iron skillet. The stove is set to high. The pledges are lined up, with their left buttock exposed.

Outside on the street, two boys fight each other over a pothole, proving to a refereeing pledge that they aren’t sexual assault risks. Chicago wind cuts through the night, leaving first-years shivering in “going-out tops,” strategically pulled down to improve chances of party entry.

This part of the intellectual experience certainly was not in the University brochure. After all, some lessons aren’t meant for the public syllabus.

Despite the mythos, the horrors, and the cautionary tales from those who came before, the new first-year students await entry to the party with excitement, in all their awkward, anxious glory.

For this frat house is their Berghain, the pledge at the door is their bouncer.

A lone first-year student stands at the foot of the house, a towering monolith of red brick and fragile masculinity. He stares at the men standing inside. Their jawlines all seem to have been sculpted from the same white granite block of privilege and ignorance.

His heart is pounding in his chest as he approaches the door—no, the gate—to the kingdom.

The door opens. The music is deafening. The floor is sticky with beer and sweat. The air is thick with the berry vapes and anxiety. This, they will tell you, is what brotherhood feels like.

This is the place where men are made, or at least where they think they are.

A pledge at the door stares him up and down. A lion eyeing a particularly foolish gazelle.

He steps forward. It’s Judgment Day.

A question is coming. He already knows what it is.

“Name three brothers.”

He doesn’t know them yet. But he will.

Editor’s note, 11:54 p.m. September 15: Previous initials used to identify “A.” have been changed to avoid confusion with another individual.

Walker / Sep 25, 2025 at 10:49 am

Fantastic article! As someone who has been a member of the Hyde Park and University community in varying capacities for decades, I’ve long thought that places like The Iron Key Society are not at all in keeping with the overall ethos of University. I also appreciate your unpacking of the role the University plays and their general stance of plausible deniability. It is worth noting, however, that to my knowledge, the University supplies the heat to the Iron Key Society via their steam plant. In this sense, they do have some leverage, just choose not to use it. It is also interesting that if you look at their property tax records, they are listed as exempt and have not paid any property taxes for the last several years. This seems rather odd as fraternal organizations are not generally exempt. Thanks again for the great reporting!

ryan / Apr 9, 2025 at 1:55 pm

Though perhaps a quite obvious account to most of the women on this campus, I thank the author for writing this. How many more stories need to be written before students gain the courage to take action? How many more assaults? How much more abuse? They only maintain power insofar as they maintain the popularity and support of the general student body, especially the women they rely on as capital. It has to stop.

Maddy / Mar 6, 2025 at 10:55 pm

Reminds me of stories from my sister who was (briefly) in a sorority at University of Kansas: the first week of school, the frats host parties for “Shark Week” that are eagerly attended by sorority girls, first years in particular. Why the name shark week? It’s because the new freshman girls are quite literally described as “fresh meat” for the frat brothers “sharks” to tear into. And my sister awkwardly told my parents this when they asked, yet was still excited to go party for it each year…

Paolo / Mar 5, 2025 at 8:07 pm

Excellent article. I can see why so many frat brothers are crying about it on Sidechat.