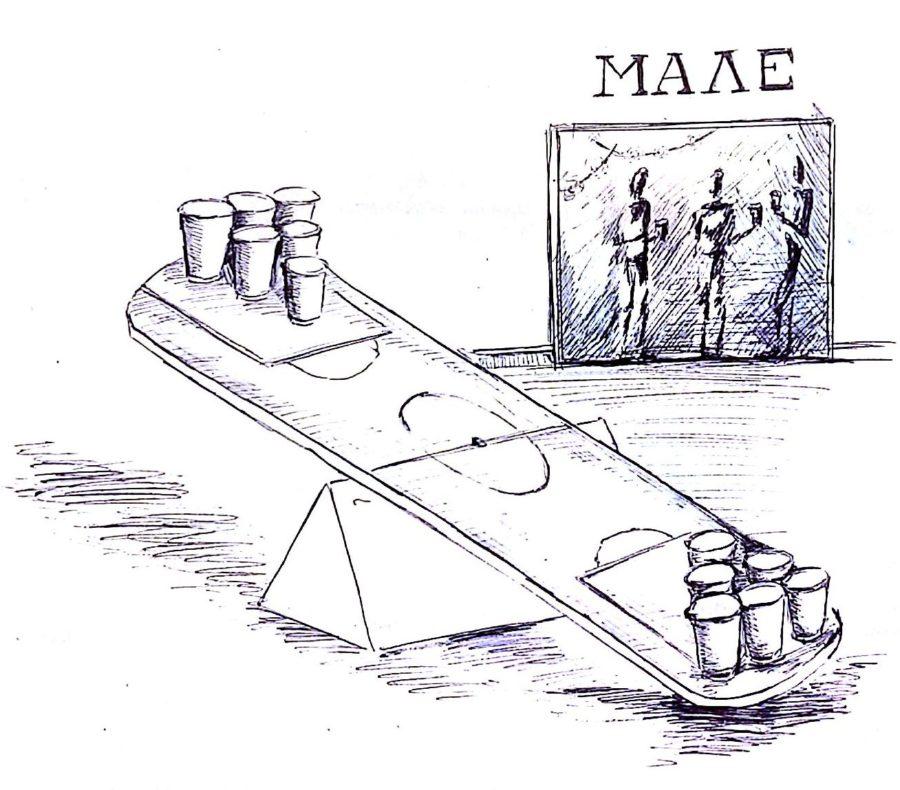

Evidence strongly suggests a link between fraternity-hosted, alcohol-fueled large-scale parties and rape. A 2007 study funded by the Department of Justice found that the frequency with which women attend fraternity parties is positively correlated with being a victim of an incapacitated sexual assault and that attendance at fraternity parties where alcohol is served is much higher among victims of incapacitated (rather than physically forced) sexual assault. Let’s be clear: these are survey data and neither of these points are proof of direct causation between alcohol being served in male-dominated spaces and women being the victim of a sexual assault, but the association should not be ignored, especially when considering how to better deal with sexual assault on campus.

The report also found that while 28 percent of incapacitated sexual assault assailants were fraternity members, only 14 percent of forced sexual assault assailants were fraternity members, which indicates that alcohol is a key factor in fraternity sexual assaults. Again, this is clearly not causation, but it lends credence to the idea that the connection between fraternities and alcohol is nuanced and needs to be closely examined. In these nuances lie many possible incremental improvements to how sex and alcohol interact on this campus.

In terms of location, a significantly higher proportion of victims reported being at a party when the assault happened. Here, having living quarters so close to the party works against the party-goers. Moving fraternity-style parties into venues without private spaces could greatly reduce the possibility for assault.

Regardless of the culture of fraternity life, students who wish to go out and meet up with their peers, especially as first-years, often head to fraternities. In order to expand their social circle or celebrate with their friends, hundreds of students rely on fraternity houses until they meet upperclassmen who host apartment parties or decide to stay within their smaller social circle and host gatherings in their dorm rooms. For many, it is an important social space, making their exploration far more dangerous than necessary.

Undergrads—even those not yet 21—should have the chance to explore all that young adult life has to offer in an environment that does not levy rape as punishment for poor decision-making.

Many of the issues regarding alcohol and sexual assault are cultural problems that cannot be fixed with a simple policy prescription. We’re better off changing how students drink through structural changes, which would begin to solve the immediate problem as we continue to have conversations about how to best effect more comprehensive societal changes.

If students were allowed to host parties in neutral spaces, women would have greater autonomy over the way that they choose to take risks and explore as young adults. One such option, suggested in an article published by *The Atlantic* last winter, are sorority parties. However, considering the strict national limitations on sororities regarding alcohol consumption, and the lack of houses for the UChicago Panhellenic sororities, it’s not the most feasible option for our campus.

Some campuses, like Hamilton College, allow undergraduates to host events in college-owned spaces, allowing clubs and local sororities (as opposed to UChicago’s national Panhellenic sororities) to host parties in neutral spaces. This gives students a chance to meet their peers in a location that puts them all on a level playing field. Intentionally or not, colleges that don’t have similar policies push college drinking into underground spaces, often fraternities, that simply don’t have the same oversight or third parties ensuring that party-goers play by the rules.

In recent years, social reformers have come to recognize the value of implementing policies that make an inherently dangerous activity less so. Like needle exchange programs for heroin users or providing free condoms to populations at a high risk for HIV infection, allowing undergraduates to drink in University spaces would make a risky activity less dangerous. All these policy changes aim to allow people to express their autonomy more safely, instead of simply preaching abstinence. By allowing parties in neutral locations, the University will be enacting a similarly-enlightened policy, by providing students with the opportunity to drink and interact with each other without sacrificing their own safety. Though the University currently tries to help its students drink more safely, its current policy forces large parties to be held in fraternity houses, giving fraternity members undue control over the spaces where alcohol is consumed. We should be giving individual students autonomy over their own alcohol consumption, should they choose to drink.

In principle, the University should not encourage underage students to drink, and opening University spaces would make it easier for them to drink. But the alternative—the status quo—is worse. Sororities and unaffiliated women will continue to rely on male-controlled spaces to hold their alcohol-fueled events, which increases the likelihood that one of them could be sexually assaulted.

It’ll be understandably tough for the University of Chicago to put practice over principle, but if it means fewer women being sexually assaulted, it would be unconscionable not to.

The University has made strides in recent years in educating students on the causal link between alcohol and sexual assault and that students who choose to drink have the responsibility to know how to do so safely. By implementing our suggested policy, the University can transform their advice on how to reduce one’s risk to being assaulted into protections against letting those potentially risky situations ever arise in the first place. It’s clear that there’s still more to do in reforming attitudes that lead to sexual assault but changing this policy is something meaningful the University can do now as our community and nation work to better understand the issue of sexual assault on campus.

Meggie Carroll is a second-year in the College majoring in Law, Letters, and Society.

Forrest Sill is a second-year in the College majoring in computer science.