On June 14, the dean of the Division of the Arts & Humanities (AHD) formed and immediately charged five “working groups” with proposing significant reforms on the structure of departments; language instruction; and doctoral, master’s, and undergraduate education. The committees have until August 22 to submit their recommendations to the dean, who will in turn forward them to the provost by August 25. This timetable means that a program of reform intended to change nearly every aspect of academic life will be completed and advanced beyond the division in exactly the interval during which neither departmental nor divisional meetings take place. To achieve this unseemly haste, the process allows neither for consultation with departments nor for comparative and historical study.

Everything about the process, stated rationale, and likely outcomes of this program of reform strikes me as emblematic of the current trajectory of the University of Chicago and, indeed, of higher education as a whole. In what follows, I seek to analyze this development in terms that clarify the stakes, both internally to the University and externally to colleagues in higher education.

I first explore the charges of the committees and the rationale they have been given, both for acting at all and especially for acting quickly. I then analyze the implications of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) and other federal actions for the University of Chicago. This analysis leads to the question of the incidence of funding changes at the federal level for the budget of the Division of the Arts and Humanities.

The thrust of this analysis is that the University has undertaken extraordinary quantities of leveraged spending in ways that benefit select units, while others, who have achieved high international ranking with little aid from capital spending, have instead suffered from a withdrawal of operational support in order to finance those endeavors. The present moment of reform brings that long trend to a crisis point. To understand the University’s willingness to dismantle its own excellence, I turn to an earlier moment of panicked reform induced by an earlier stage of this prolonged financial crisis, namely the expansion of the College in 2017. This leads to some final reflections on the maintenance of University ideals in an age of instability.

The Reforms and Their Rationales

For the sake of brevity, in this section I focus on the charge to the “Divisional Organization Working Group.” The Divisional Organization Committee has been invited to consider the questions: “What is the right number and size of departments for the division in 2025 and beyond? Could we envision an organization with @8 [sic] departments?” Subsequent bullet points suggest that a reduction in the number of departments will reduce “administrative costs” and “administrative burden.”

Merging disciplinary departments into larger entities has a long history in American higher education. Reforms of this kind are a feature of life at second-tier public universities. The School of Languages and Cultures at Purdue University, for example, has a Department of American Sign Language, Arabic, Classics, Hebrew, and Italian, or AACHI. But one doesn’t major in AACHI! Instead, majors and minors are offered in the constituent disciplines of the agglomerated department, which raises the question of whether lumping units together does in fact reduce administrative costs and burden. This question could have been studied by the Divisional Organization Working Group via data and analysis from comparative cases, which in turn might have justified “@8” as the optimal number of departments for the Division. But this work was not done. Instead, the committee has been invited to reduce 15 departments to eight; to identify what those eight will be; and to provide an intellectual rationale for a goal that was determined before the rationale existed.

This is not an academic process.

The charge to the committee admits that it must work on a “a very short timetable.” In speaking to the working groups, the dean has justified the need for haste on three grounds:

- The dean wishes to “get ahead” of a review of the structure of all schools and divisions requested by the Committee of the Council.

- The provost has said that any unit with fewer than 15 tenure-stream faculty members will be dissolved or merged.

- The budgets of the Division and University are under stress, due to the federal context.

As regards the Committee of the Council, I can find no evidence that such a review is taking place. It was not on the agenda of the Committee of the Council in academic year 2024–25 (AY25)—I have spoken to members of that committee. Nor is it on the agenda of the committee in AY26. (I have been elected spokesperson of the committee for AY26, and the faculty on the committee have met to discuss its agenda, with the caveat that the committee is not formally inaugurated until September 25, 2025.) Nor, frankly, is this sort of thing within the committee’s power or traditional functions.

Nor have I been able to verify the second claim. A survey of the webpage of each department in the University suggests that only one unit in the Division of the Social Sciences (SSD), perhaps only one in the Division of the Biological Sciences (BSD), and none in the Physical Sciences Division (PSD) would fall below this threshold. (It is not always simple to resolve whether faculty on departmental pages have their primary appointment there.) Nor has any faculty member in those other “small” units, in response to my inquiries, confessed to having heard of this plan on the part of the provost. Apart from the fact that I have been unable to verify that such a plan exists, the use of quantity as a way of parsing institutional efficiencies and determining the fate of disciplines is too crude to be believed. The professional schools have no departments. Perhaps their form is ideal? If so, we should eliminate all departments. Or perhaps the professional schools defy analysis because our yardstick can’t measure them? The whole idea is beneath the dignity of a research university.

I set aside for now the questions of whether merging departments saves money and, if so, how. I turn instead to the question of whether the University’s fiscal situation and the current federal context demand a response of this kind and on a timetable such as the dean of the Division of Arts & Humanities has imposed.

The Federal Context and the University Budget

The hostility of the Trump administration and the Republican-majority Congress toward research and higher education scarcely requires documentation. Their actions target several significant sources of University revenue, including research funding—both the total amount available for grants but also so-called indirect costs—as well as international student enrollment, Medicaid patient revenue, and endowment payout. In some cases, there remains significant uncertainty about the consequences of any given action for the University’s budget; some of these concentrate in areas currently subject to litigation, and some are the subject of future appropriations bills. Nevertheless, the passage of the final version of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act has brought some clarity to the situation. Here I offer a sketch sufficient to understand the implications of the federal context for the University of Chicago and, by extension, for the allocation of resources within the University. (To a point, this section expands on a study that I published recently in the Chicago Tribune.)

Most people experience the finances of higher education as payers of tuition. But at the University of Chicago and the other private research universities, tuition comprises around 20 percent of revenue if one focuses on the university alone. (In the University’s 2024 financial statements, tuition is $609.991 million out of the total $3.207 billion in revenue.) The rest derives from endowment payout; contracts and grants; the provision of “auxiliaries: (an opaque term that refers to services, especially room and board); and the like. It is of the essence as well that, across higher education, revenue and expenses tend to be extraordinarily stable, the ambitious talk of revenue growth by university leaders notwithstanding. The lack of any conceivable quick fix is precisely what makes the University of Chicago’s debt situation both irresponsible and intractable.

The Trump administration is upending decades-long stability in science funding for projects housed at universities in two ways. First, it proposes radical cuts in the funding of the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In the case of the NSF, the president’s financial year (FY) 2026 budget request for the NSF is $3.9 billion, a 55.8 percent cut on the previous year’s enactment (which was itself reduced from the then president’s request). (As is well known, the NSF has already been seeking to curtail reimbursements for contracts long since signed.) In the case of the NIH, the president’s appropriations request for FY26 for the Department of Health and Human Services is 26.2 percent below the enacted budget for FY25 ($93.8 billion from $127 billion), including a nearly $18 billion reduction in funding for the NIH. If anything like these cuts are enacted, there will be a great deal less grant money for teams to compete for.

Second, for anyone who wins a grant, the Trump administration proposes to cap so-called indirect cost recovery at 15 percent. The distinction between direct and indirect costs traces the difference between the immediate costs of a specific piece of research and things that cannot be directly connected to a particular project but which are necessary for research. Indirect costs therefore comprise things like heating and air conditioning, building maintenance, libraries, administrative costs for compliance issues, and so forth.

Formally, both direct and indirect costs are paid by the federal government in the form of reimbursement after the expenses are incurred. (Hence the opportunity for the Trump administration to covertly intervene in existing contracts by simply not processing reimbursements, an issue that is very difficult to litigate because it is experienced as a delay.) Despite the status of these funds as reimbursements, universities count on them in two ways. First, universities essentially build research buildings in the sciences as loss-leaders. Decades of stable funding according to negotiated rules have led universities to expect the cost of new facilities to be substantially repaid over time via funded research. Of course, the faculty have to be good enough to win that funding through individual applications to the federal government, and the prospect of a diminished overall pool of available grants is a threat to the entire ecology of higher education. In addition, facilities eventually require repairs and renovations that can cost as much or more than the original cost of construction.

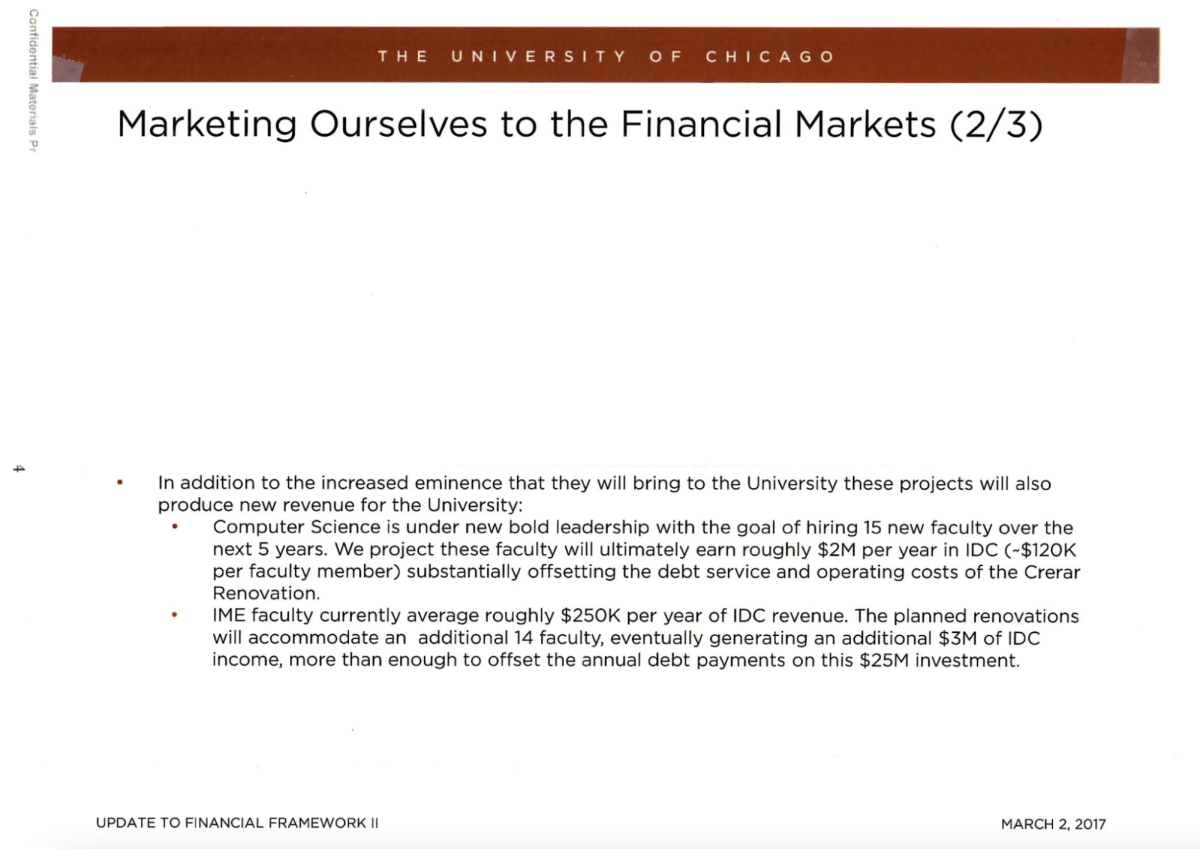

Second, the University of Chicago has occasionally calculated the per capita rate of indirect cost recovery in given fields, to be weighed as a factor when it considers whether to expand its faculty in any particular direction (see Figure 1). Those faculty are then employees, whose salaries and benefits contribute to annual operating costs whenever they are not covered by grants. The diminution of available grant money is therefore in itself a major threat to operating costs. For its part, the attack on rates of indirect cost recovery is an assault both on past capital expenditures, which the University has financed through debt and expects to repay, and on future operating expenses, which the University has costed out at rates of indirect cost recovery on which it can no longer rely.

The University of Chicago is also deeply vulnerable to the OBBBA’s slashing of Medicaid, which the Congressional Budget Office estimates will deprive 16 million people of health care after the measures take effect on January 1, 2027. Located on the South Side, 18.8 percent of UChicago Medicine’s $3.996 billion in FY24 patient revenue derived from Medicaid. By contrast, Northwestern Medicine derived only 8 percent of patient service revenue from Medicaid. This matters because, while the margins on Medicaid revenue are much lower than those on private insurance, they are clearly better than seeking to serve populations without health care at all. What is more, the University of Chicago is unusual in that its medical center’s revenue contributes directly to the financing of basic science departments in the BSD and, in my view, the University is simply unequipped to make up those costs via other means.

The University of Chicago derived 16.4 percent of its FY24 revenue from endowment payout. (The number is 7.3 percent when one consolidates the University and UChicago Medicine.) The versions of the OBBBA proposed by the House and Senate differed, but the original proposal in each chamber would have raised UChicago’s tax burden quite substantially, while the version proposed by the House in particular would effectively have penalized universities for admitting larger numbers of foreign students. This was a major cause of concern in May and June. However, thanks to the Senate Parliamentarian, who disallowed a clause that excluded foreign students from the count of enrollment, the excise tax on the University of Chicago’s endowment will remain unchanged. That’s right: the increase in FY26 on FY25 will be $0.00.

We return to tuition. Tuition is a leading source of unrestricted revenue for all universities. (Restricted revenues are funds like grants and gifts that can only be spent on a named purpose.) But tuition cannot solve the shortfalls that are coming, for four reasons. First, as I have already said, tuition revenue is only a small part of the University of Chicago’s overall revenue. Second, the University must use a substantial portion of its unrestricted revenue to pay the interest on its extraordinary debt. Third, tuition revenue is particularly inadequate to cover the cost of instruction in the sciences, precisely the area where the Trump administration proposes its most radical cuts. Fourth, tuition income remains vulnerable to the Trump administration’s effort to discourage foreign students from attending American universities.

It is crucial to know that very few people pay the advertised tuition at America’s leading private universities. In FY21, UChicago reported to the Department of Education’s IPEDS database net tuition revenue of $31,500 per undergraduate. (More recent data is available in the form of net price per student in each incoming cohort.) Because the overwhelming majority of American universities that admit students on a need-blind basis do not extend this policy to international students, foreign students pay much higher rates of tuition. In effect, they subsidize American students. At the University of Chicago, 24 percent of students are international, including 15 percent of undergraduates. Everything the federal government is doing—including a full pause on processing student visas—will make international students harder to recruit. What is more, the ability of international students to come to America, and the ability of American universities to host them, is an area where the executive branch retains great power, largely unconstrained by the other branches of government.

The Singular Self-Reliance of Faculty in the Humanities

All of this raises the questions: What is the incidence of the federal context for the Division of the Arts & Humanities? How much does the Division “cost” the University?

Contrary to much vernacular opinion, faculty in humanistic fields and the interpretive social sciences are the only faculty in the arts and sciences who systematically pay for themselves: they do not need expensive buildings; they do not require substantial material infrastructure or expensive data sets for research; and the provision of instruction in their fields is cheap.

Consider, for example, the budget of the Division of the Humanities (HD), as it was then named, in FY21 (Figure 2). Perhaps the most important, immediately visible fact is that 98 percent of academic compensation, which totaled $45.034 million, was paid for through undergraduate tuition and endowment. This is seen not simply in the pie chart of “Academic Compensation by Source,” but also in the comparison of “Revenue by Source” to “Expenses by Type.” The largest asymmetry, such as it is, between revenue and expense lies between “Graduate Tuition,” derived from M.A. programs, at $46.383 million, and “Graduate Student Support,” which largely goes to Ph.D. students, at $53.298 million. But some portion of that gap is filled by endowment support, at $5.111 million. The “gap” is a mere $1.8 million.

The situation of humanities faculty in FY22 may be taken as emblematic of the budgetary implications of faculty in all humanistic fields, as well as the non-quantitative social sciences. Within the arts and sciences, they are unique in the extent to which they fund themselves on the basis of endowment and tuition alone, without subsidy from the center.

Given that the excise tax on the University of Chicago’s endowment will change not at all, and given that the Division of the Humanities previously derived only 1 percent of revenue from federal grants, it seems fair to say that the exposure of the Division, narrowly construed, to the current federal context borders on nil. In short, the argument for precipitous change, enacted without comparative analysis or due consultation with the affected communities, based on the current federal context, is nonexistent.

Of course, the fiscal situation of the University could be so dire that its leadership might elect to make units that are largely unaffected by the federal context “pay” for “needs” in other units, including—and perhaps especially, in UChicago’s case—debt-financed capital expenditures. Let me make two points in this regard.

First, the University has long since been engaged in a project of reducing its commitment to humanistic departments and in fundamentally altering their character. Figure 3 tabulates the population of doctoral students in the three units in which the university funds doctoral education largely from its own resources: the Divinity School, the then HD, and the SSD, with their total in red. The next columns tabulate the populations of doctoral students in the BSD, the basic science departments of the PSD, and the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, with their total in black. (All data are taken from the autumn quarter reports of the University registrar.)

From a peak in 2004 with 2,508 students, the number of doctoral students in the humanities and humanistic social sciences declined every year for nearly 20 years, to a (perhaps temporary) plateau of 1,080—a decline of nearly 60 percent. By contrast, the number of doctoral students in STEM fields has grown every year for the last 15 years, reaching roughly double the number in 2024 that had existed in 2009. I assume that a large portion of that increase results from an increase in federal support for scientific research. I don’t quarrel with the increase as such. I simply pose the question whether further cost-saving in humanistic fields—which to an astonishing degree pay for themselves—in response to internal and external pressures that they did not contribute to create, is appropriate.

A second area of potential investigation, not captured by a chart of operational expenses, is capital expenditures. A vernacular understanding of capital expenditures focuses on new construction. In reality, a surprisingly large amount is devoted to alterations and repairs to existing buildings, as well as equipment. In a 2017 report by the provost to the Financial Planning Committee of the Board of Trustees, the provost estimated $638 million would be spent on “alterations, repairs, and equipment” between FY16 and FY20, while $671 million would be spent on capital projects over the same period. As an additional data point, UChicago’s 2009 strategic plan outlined a plan for $370 million in renovations to PSD buildings and a further, time-staggered expenditure of $370 million for a Center for Physical and Computation Sciences.

This leads to two conclusions. First, on the basis of an imperfect dataset—because I don’t have a full run of reports on capital expenditures—I can document roughly $1 billion of capital spending devoted to “renovations and repair,” which must be combined with the cost of construction of any given building when estimating whether “indirect cost recovery” will ever “repay” the University’s investment. (It will not.) Second, between 2013 and 2020—again, working with an imperfect dataset—itemizations of “major capital projects” by the University’s leadership to the Financial Planning Committee of the Board of Trustees list none for the Humanities Division. Nor were any named in the strategic plan for 2009, though, in a longer term accounting, one should include the Reva and David Logan Center, the planning of which began in 2002 and which was inaugurated in October 2012.

In short, capital investments in the Division of the Humanities between 2009 and 2020 totaled perhaps 1 percent of the total, but very likely less. As a provisional matter, one might draw the lesson that it doesn’t pay to be inexpensive, because then people feel free to take your stuff. If you are expensive, more shall be given.

Educating Undergraduates as “Marginal Cost”

In order to establish an interpretive framework that allows us to understand what UChicago is now doing and to predict where we might go in the future, it is instructive to examine the University’s response to an earlier stage in its ongoing financial crisis. Over several articles, I have written about numerous aspects of the University’s liquidity crisis in 2016 and 2017. Many of the facts are well-known. I focus here on the relationship between the University’s actions regarding academic personnel as documented in its own datasets, on the one hand, and on the values that seem to inform the University’s policies, as these were discussed before the Financial Planning Committee of the Board of Trustees.

The University’s 2009 strategic plan argued that increasingly poor ratios of tenure-stream faculty to undergraduate students “threaten[ed] our core ethos as a University that places a premium on rigorous inquiry” (Figure 4). Despite a vow then to increase the number of tenure-stream faculty, the information provided by the registrar’s census of the student population, a trustees’ databook from 2019, and recent figures from data.uchicago.edu reveal that our student-to-faculty ratio has, in fact, grown steadily worse: rising from 5.83 in 2011, to 6.13 in 2017, to 6.71 in 2023.

In particular, as I have documented from the College’s own reporting (Figure 5), the fiscal crisis of 2016 led to massive hiring of instructional faculty. What I can now show is that, in the meeting of the Financial Planning Committee of the Board of Trustees, the provost proposed to ameliorate part of the University’s fiscal problems by a further expansion of the College. What is more, the provost asserted (Figure 6):

If, as we believe, the existing capacity of our tenured and tenure track faculty can absorb most teaching responsibilities for new undergraduate students, the marginal cost of adding these students would be fairly minimal (~10-20% of net tuition). Assuming normal tuition growth and discounting these additional students would net significant additional revenue, thus contributing materially to ongoing operations.

In short, in the analysis and language of the University’s leadership, the cost of educating the 500 students who were added to the College in that expansion would amount at most—which is to say, at worst—to 20 percent of their tuition. 80 percent would be available to service debt or for operational expenses that the University’s own leadership identified as unconnected to undergraduate education.

At America’s leading research universities, tuition always subsidizes research. This should not surprise anyone. Nor is this wrong in principle. Students benefit in many ways from the University’s research enterprise, both directly, through exposure to a culture of rigorous inquiry, and reputationally, as the value of their degrees and, indeed, the degrees of all alumni reflect the University’s contemporary overall reputation. Nonetheless, these were not the terms in which the matter was discussed, and one must still acknowledge that the path chosen in 2017 amounted to a repudiation of the “core ethos” of populating the University and its classrooms with research faculty as articulated in the 2009 strategic plan.

The turn away from research faculty and toward instructional professors was done hastily and without academic study of relative pedagogical effectiveness. The process, timetable, and outcome certainly appear to have been determined by financial considerations alone.

This brings me to the charge delivered to the “Languages Working Group.” Among other questions, this committee was asked to consider whether a given class should be taught every year, whether there are languages we no longer need to teach, whether there are opportunities to partner with peer institutions to share language instruction, and “how [we can] use technology… while maintain[ing] institutional strengths and standards.”

It is hard to read these questions and not conclude that the committee is being asked to reduce offerings, send students across Chicago or onto Zoom to study particular languages elsewhere, and reduce the cost of instruction by using AI. Changes like these might reduce the “marginal cost” of educating students from 20 percent of their tuition to something more like 10 percent. For my part, I am tempted to say that students whom we send elsewhere for instruction, or whom we educate via ChatGPT, should have their tuition bills reduced.

To resume: the University’s deficits and debt load have grown nearly every year since 2017. What reason is there to think that a ruthless fiscal logic won’t continue to drive academic decision-making? The language employed by the University’s leadership to discuss College instruction in 2017 induces the fear today that other successful and fiscally responsible units will also be treated like an ATM with which to finance priorities beyond themselves. Is this the lens through which to interpret the process now underway in the Division of the Arts and Humanities?

Conclusion. Could We Care Less About Education?

The University of Chicago is a complex organization. It pursues multiple goods, some of which overlap and some of which relate to one another only obliquely. The analysis performed in this article is informed by, and itself intends to further, a particular vision for the University of Chicago and, by extension, the research university as ideal. Other people will have different visions. We should welcome public conversation about what those are, and that conversation should be informed by the fullest range of information.

My analysis has had three targets: the processes by which the university’s leadership enacts reform; their long-term and large-scale choices about which units should flourish and which can be weakened; and the fact that reckless spending has sharpened and continues to exacerbate the scale of the trade-offs that these policy preferences entail. I also lament how hard it is to understand the University at this scale. The University of Chicago’s pathology for secrecy regarding the simple facts of its own operations does not suggest confidence on the part of its leadership, despite their power. They should announce their vision proudly and provide the data for it to be analyzed and discussed.

As regards the reform and reorganization of the Division of the Arts and Humanities, what we appear to have is a plan in search of a rationale; we’re going to disrupt and then see what happens; we don’t even know whether we will achieve the efficiencies that are the reform’s stated goals, let alone what their effects on academic excellence and institutional reputation will be. We will simply fracture the homeomorphy between pedagogy, local institutional life, and national and international disciplinary organizations that has long sustained us and hope for the best.

Clifford Ando is the Robert O. Anderson Distinguished Service Professor in the Departments of Classics and History at UChicago and an Extraordinary Professor in the Department of Ancient Studies at Stellenbosch University.

Editor’s note, 10:50 p.m. July 28: This article previously stated that the Committee of the Council for 2025-2026 is formally inaugurated on September 1, 2025. This has been corrected to September 25, 2025.

Carl Southwell / Nov 30, 2025 at 8:45 pm

Ando’s account maps to Cory Doctorow’s cycle of platform decay he calls enshittification:

* Serve the public good: To a large degree, UChicago built its reputation on rigorous inquiry in humanities and social sciences.

* Shift to marketization: Expansion of the College (2017), debt‑financed STEM investments, royalty chasing.

* Exploit all sides: Humanities cutbacks, adjunctification, tuition leveraged to service debt, faculty sidelined from governance.

In this framing, UChicago’s leadership is hollowing out the very departments that made us distinctive — a textbook case of enshittification applied to higher education.

Concerned Alum / Aug 16, 2025 at 3:56 pm

I can’t seem to view Figure 1 properly in either Firefox or Chrome. Can someone fix the graphic?

Dr Omar Altalib / Aug 14, 2025 at 5:00 pm

Thank you for publishing this comprehensive article that highlights the critical challenges facing the University of Chicago!

Tallies Ream / Aug 2, 2025 at 9:26 am

University of Chicago is gutting its Division of the Arts and Humanities so that it can start a new Division of Data Science. The name is not final yet but it will be something to that effect and the process has already been underway for several years. Loads of people have already been hired. It just hasn’t been called a “Division” yet.

Ando is puzzled because he doesn’t understand this basic ploy: You don’t shut down an old unit and then start a new unit to replace it because people will be upset. You start the new unit first, create a deficit, blame it on the old unit, and then use it as justification to close or shrink the old unit.

Young / Aug 19, 2025 at 2:51 pm

Ando is not the one who is puzzled here. A huge draw of UChicago has always been its humanities and social sciences. If the administration wants to gut their golden goose–a goose that pays for itself even if it doesn’t fetch enormous amounts of capital–to chase after a fad of the day, then it’s clear someone higher up in the administration is puzzled. “Basic ploy” doesn’t mean that it is a “good ploy.”

Young / Aug 19, 2025 at 3:42 pm

Ando is not the one puzzled here. Social sciences and humanities have been a huge draw for UChicago. It doesn’t bring in big bucks, but at least it pays for itself. Killing one’s golden goose to chase the fad of the day—if this is a “basic ploy”, it sure isn’t a very good one.

Zachary Sheldon, Ph.D. 2020 / Jul 31, 2025 at 11:46 am

Commentators who are criticizing the author seem not to understand what the University of Chicago is or why it was successful prior to the disastrous 2016 expansion discussed in the article. But this is a wonderful piece of research that provides context and clarity to my own experience as a graduate student and postdoc throughout this period of change. The thesis is clear and simple: Greedy incompetents brought the university into a financial crisis by cheapening its brand as leverage for debt financing. They knew what they were doing, and they were determined to shoot themselves in the foot anyway. Critics who suggest that faculty somehow brought the school into this crisis have no idea what it was like to work at Chicago during this period. As the author states, value-creating employees were completely marginalized and ignored by the people agreeing to more and more debt. And the more one spoke out about the short-sighted and wasteful decision-making, the more they were told to stay in their lane and leave the budgeting up to the deans and provosts. Now that the political winds have shifted away from Chicago, the city, and its Democratic money machine, the chips are down and there’s nowhere for the debtors to hide. But this piece only touches on this administration’s culture of secrecy and their contempt for value-creating faculty and graduate students who tried, again and again, to warn them against killing the golden goose that was Chicago’s reputation. We all know that in American business, whether we’re talking about the University of Chicago or Burger King, bad executives can saddle a company with debt then lay everyone off and walk away from the mess they made.

Matthew G. Andersson, '96, Booth MBA / Jul 26, 2025 at 10:53 pm

The author’s efforts are commendable. UChicago however remains under-capitalized, with a strategic mismatch in operations and finance. Its sensitivity to revenue variation, therefore leads to compromise, and its governance, to problems in decision-making. Instead of $10B, why doesn’t it have $20B; if $20B, why not $50B? There is also a mismatch in leadership. Compared to Harvard, Yale and Texas, the three richest universities in America, Chicago is operating at one-fifth the capital level. The “Big Three” face no urgency or strategic imperative per se (although they will be obligated to make significant structural changes over time). Texas in particular, the wealthiest of all US universities, in part through its permanent university fund, may provide a model for other states. See “Everything a University Does Can Be Done in Half the Time and Half the Cost,” and “Academia: The Worst-Managed Industry in America,” in the National Association of Scholars: It is instructive to consider university administrative behavioral difficulties, including maladaptation and current dissociation. These stem partly in ways still not fully appreciated, from what UChicago alumnus and former White House advisor Dr. Scott Atlas has called “the most tragic breakdown of leadership and ethics in our lifetimes” (WSJ, March 3rd, 2025).

T Whyte / Jul 26, 2025 at 4:27 pm

I concur with “TL;DR” and “JJ.” This meandering diatribe is a transparent attempt to reassert relevance under the guise of principled dissent. Nothing more. The author devotes thousands of words to lamenting departmental mergers—does he seriously believe maintaining 18 under-enrolled fiefdoms is viable in 2025? He wrings his hands over efficiency yet offers no alternative beyond preserving his own patch of turf. He denounces administrative streamlining as if universities exist to serve tenured egos, not students. We’re told this reorganization is reckless, undemocratic, and destructive. Yet he presents no concrete evidence, only florid abstractions and nostalgia for a structure that’s clearly broken. Does he truly think the solution to financial strain is to ring-fence departments that contribute the least and consume the most? At every turn, the author attempts to elevate personal grievances into critique, casting himself as a moral compass while ignoring that hard choices are the province of leadership, not sideline theorists. His overwrought and ideological framing and refusal to grapple with the real constraints of university governance make clear one thing: he has no workable vision! No, only the wounded pride of someone whose influence is waning.

ConcernedBiologist / Jul 27, 2025 at 8:21 pm

The humanities place less demand on university funding than the natural sciences, as was stated in this well sourced analysis. Not sure why you think they “consume the most”?

TW / Jul 30, 2025 at 8:15 pm

Because the claim is a convenient fiction. The humanities may not require expensive lab equipment, but they’ve quietly bloated themselves through ballooning administrative overhead, proliferating DEI sinecures, and niche centers that do little but host self-congratulatory panels. “Less demand” ignores the full cost of subsidizing intellectually stagnant departments that produce negligible research output and enroll fewer and fewer students each year. A low burn rate is still a burn. I thought that was self-evident.

J / Aug 14, 2025 at 7:47 pm

You out yourself with the phrase “DEI sinecures”. Me thinks that your critiques of the humanities are actually the convenient fiction – convenient to the rationale you’ve invented for why they’re not needed. It’s sad.

Albert Steptoe / Aug 15, 2025 at 5:06 pm

‘proliferating DEI sinecures’ rather gives your game away…

Geisteswissenschaftler / Jul 28, 2025 at 5:12 pm

Care to explain which departments “contribute the least and consume the most?”

Avid Dence-Pliz / Aug 19, 2025 at 2:55 pm

Care to support your claims with concrete data? If not, your counter-argument is nothing but an ad-hominem.

TL;DR / Jul 26, 2025 at 12:30 pm

Why is this professor, who clearly despises the institution that signs his checks, given free rein to dress up self-preservation as moral clarity? This screed reads as a litany of personal grievances masquerading as institutional concern.

Mark Weinstein / Jul 30, 2025 at 1:36 pm

Because that is the meaning of “Academic Freedom.” Without it we may well be forced to drink hemlock.

J. / Aug 14, 2025 at 7:50 pm

The University of Chicago in large part built its reputation on its humanities and social sciences departments. Many of these departments are among the best in the world. Perhaps you only think about STEM or some rightwing extremists in economics, but for many of us, UChicago humanities is a beacon. It has long set the standards that everyone else follows. Now, the university is out to kill its reputation. This will make even the departments you prefer to lose their stature. It is a self-own. It is suicide.

Art Dodger / Jul 26, 2025 at 8:42 am

I wish Clifford Ando could become UChicago president or provost, as it is nice to have a clear and detailed explanation of the challenges the university is facing rather than infrequent and cryptic communications such as the community currently receives (the provost’s occasional budget townhalls notwithstanding). If the data reported here are accurate, it does seem as if the university is robbing the humanities to pay for shortfalls in other divisions, general overhead, and debt. Between Republican funding cuts and AI, the STEM fields that students have been flocking to for the past 20 years may now be turned upside-down, and the critical-thinking skills students acquire through a liberal arts education may become all the more crucial.

JJ / Jul 26, 2025 at 12:39 pm

…did you actually read this manifesto, or merely skim it for a conclusion that confirmed your priors? It is overwrought and ideological, meandering in scope, and attempts to elevate personal grievances into grand institutional critique, all while positioning the author as a moral authority. It is not a serious or coherent diagnosis of institutional dysfunction.

J / Aug 14, 2025 at 7:48 pm

“Ideological”? The essay supplies facts and reasons with the data. If you’re prone to call that ideological, you need to look int he mirror.