The Janes: The Story of UChicago’s Clandestine Abortion Ring

From 1969 to 1973, the Janes, which included many UChicago students, facilitated an estimated 11,000 abortions.

Some members of the Janes in 1968

February 11, 2023

Content warning: This article includes mentions of sexual assault and suicide.

During UChicago’s 1968 first-year orientation, Ellen Diamond wasn’t getting to know her classmates, exploring campus, or getting acclimated to college life. Instead, she spent her first week on campus scouring Hyde Park for a pregnancy test.

Clutching a positive test, Diamond realized that she did not want a child at that time. Yet in the years before the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, she could not legally get an abortion in most of the U.S. Diamond was desperate. Fortunately, she had the resources to travel to Montreal to terminate the pregnancy.

Diamond was not the only person experiencing an unwanted pregnancy during a time in which abortions were illegal. When she later spoke with her mother and grandmother, she learned about her grandmother’s own experiences with abortion—it seemed as if every female relative had had an abortion, Diamond reflected.

In response to needs like those of Diamond, the Jane Collective was born. A clandestine abortion ring run in part by young UChicago students, the Jane Collective organized and performed over 11,000 abortions for those in Chicago between 1965 and 1973. Orchestrating an underground abortion network was no small task; in their fight to advocate for women’s rights, the Janes had to overcome both a system working against them and the risk of arrests.

A quick note on terminology: This article focuses on a time period before a clear vocabulary for discussing transgender and nonbinary people was widely available. Consequently, this article refers to the Janes and the people they helped as women.

1965: The Jane Collective is Born

“Pregnant? Don’t want to be? Call Jane.”

Posters with iterations of this phrase and a phone number attached to it were scattered around Hyde Park and the greater Chicago community, serving as beacons for women seeking to get a then-illegal abortion without leaving any incriminating details for authorities to follow.

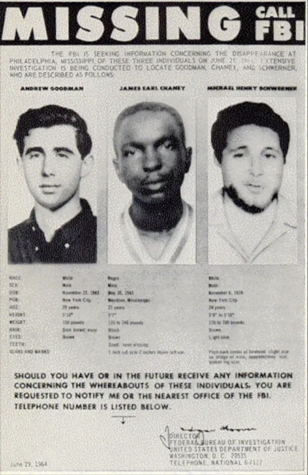

The Janes, formally known as the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation, or the Service colloquially, originated in 1965. The group was founded when a friend asked then–second-year Heather Booth to help him find an abortion provider for his sister, who was “nearly suicidal,” Booth explained in an exclusive interview with The Maroon. Booth had a history of social activism, spanning back to the 1960s’ civil rights movement, when she spent her first-year summer in Mississippi educating Black voters on their rights. While there, three student volunteers were killed by the Ku Klux Klan, and Booth herself was arrested.

“I learned some very key lessons, the most important of which is that if you organize, you can change the world. But you need to organize, and with love at the center. The other thing is sometimes you need to stand up to illegitimate authority,” Booth said.

Through word of mouth, Booth became known as a person who could connect women to a doctor, Theodore Howard, who ran a clinic on 63rd Street and could perform an abortion. Howard himself also had a background of civil rights advocacy and was, per Booth, a “very courageous civil rights leader” in Mississippi—he gained national attention in part because of his role in calling for the investigation of the murder of Emmett Till.

Booth’s services grew into what was later referred to as the Jane Collective, officially established in 1969. Born in the Hyde Park area due to Booth’s affiliation with the University, the Janes operated throughout Chicago by both UChicago students and women in the greater Chicago area. Within Hyde Park, UChicago students spearheaded local efforts, providing abortions for those who did not have the financial resources to go to places where abortions were legal.

A woman seeking an abortion would first call the number on the poster and leave their information on an answering machine. From there, a Jane member, the position titled “Callback Jane,” would respond to the message and write pertinent information via a two-card system. One card went to a scheduler, called “Big Jane”; “Big Jane” managed the logistics, such as coordinating a location and someone to perform the abortion. The other card went to a counselor.

One such counselor was Sheila Smith Avruch (A.B. ’72).

Avruch joined the Janes in 1971, her third year at the College, after receiving an invitation from a friend’s roommate. She had earlier heard talks of an underground abortion counseling service and attended her first Janes meeting in the fall.

“It was a little bit strange because when we walked in, the people in the meeting got very paranoid to meet us. They were afraid that we were police spies or something because we hadn’t been invited. No one could vouch for us,” Avruch recalled in an interview with The Maroon. “I think eventually they realized we were not. We went to some subsequent meetings and joined the group.”

As a counselor, Avruch would receive five to seven women per week via a notecard with their names, addresses, telephone numbers, ages, and how far along in their pregnancies they were. After calling and scheduling a time to speak, Avruch talked with each woman individually, and detailed the entire abortion process from start to finish.

“I would walk [the women] through what the experience of the abortion was going to be like, so that it wouldn’t be so frightening what had happened,” Avruch said. “I would explain that we’re going to do this and we’re going to give you these pills, we’ll give you some antibiotics, just in case, and we’re going to give you this other pill that will help your uterus contract—that kind of thing.”

Part of counseling entailed providing each woman with a copy of The Birth Control Handbook and Our Bodies, Ourselves, which was then a revolutionary feminist pamphlet and has since evolved into a full-length novel by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective.

“Back then, most people didn’t have very good information about either birth control or really the functioning of your own body,” Avruch said. “I always thought that the educational part of it was useful.”

The emphasis of the educational aspect of the Janes came in part from Booth’s experience with the resources for women’s health, or lack thereof, at the University. “A friend of mine had been raped at knifepoint in her bed in off-campus housing. We went with her to Student Health for a gynecological exam,” Booth recalled. “She was given a lecture on promiscuity.”

For some Janes, the age gap between themselves and the women receiving abortions, who would sometimes be double the age of the college student counselors, felt noticeable. “I felt young and somewhat inexperienced compared to some of the women I was counseling, because they often were older than me and had children and just had a lot of life experience,” Avruch said.

However, Booth recalled the myriad of emotions Jane affiliates and patients of all ages felt. “The most painful part of it was seeing how fearful many of the women were, who were coming through the service and didn’t feel like they had alternatives,” she said. “But there was also joy to see how grateful they were for having come through Jane.”

“The Front”

When it came time for the abortion, women would be assigned to an apartment called “the Front.” The location of “the Front” varied, but it was often a Hyde Park apartment of UChicago students such as roommates Ellen Diamond (A.B. ’72) and Amy Levine (A.B. ’72).

Students like Diamond and Levine opened not only their homes but their minds and hearts as working with the Janes broadened their understanding of women’s rights activism pre-Roe.

“We were advised to keep the interactions to a minimum, so we just offered them water to drink. We greeted them as they came in, offered them a seat,” Levine said in an interview with The Maroon. “One of the things that amazed me at the time was that I expected to see nervous teenagers. And in fact, most of the women were women of color, and most of them were in their late 20s, 30s, or even 40s.”

Like Diamond and Levine, Christina West (A.B. ’72), also offered her apartment as a “Front.” She remembers noting how the women who needed the Janes were not who she expected.

“There were women who were clearly mothers already. I think one of them even had a child with her, which was very confusing to me. Many of them were women of color,” West said. “It was at that point I realized that this was such a necessary service.”

“I remember them just looking scared. Looking in their eyes, seeing how scared they were, I would empathy for them,” Diamond recounted in an interview with The Maroon.

Once the women were ready for the abortion, a driver would take them from “the Front” to another apartment, called “the Place.” At “the Place,” Howard would perform the abortions exactly as detailed during the counseling sessions. His fees amounted to about $500 per abortion. Though the Janes were unsuccessful in lowering his operating costs, they were able to sometimes receive two abortions for the price of one or negotiate a pro bono abortion for women who absolutely could not afford the procedure.

Howard was eventually arrested, independent of the Janes, for performing abortions. He was replaced by a man only known as Mike. “Everything was safe and caring and a real community for women coming through,” Booth said. However, after a few years of this operation, the Janes learned that their “doctor” was not, in fact, a licensed medical professional. This created a crossroads for the Janes: Half of the group decided to leave, objecting that the procedures had been unsafe and irresponsible. The remaining Janes chose to learn how to perform the abortions themselves.

“I wasn’t as surprised as I probably should have been, to learn that the doctor was not licensed. I think I sort of had figured it out,” Avruch said. “I got interested in [performing abortions], and I wanted to learn how to do it.”

With the Janes performing abortions themselves, they dropped their price to $100. However, they never turned anyone away for financial reasons, taking any amount the women were willing and able to pay and sometimes performing operations for free.

The Arrest

At 11 a.m. on May 4, 1972, Avruch stood in “the Place” on her first day facilitating Jane-performed abortions. After a full morning of performing abortions, Avruch heard heavy knocking on the front door that rattled the apartment.

“Suddenly, we heard this huge noise. We realized it must be the police, so we locked the door,” Avruch said. “We then took the [abortion] instruments, looked to make sure nobody was beneath the high rise, and threw them out the window.”

The women, including seven Janes, waited in the bedroom for the police to burst in.

“Eventually the police kicked [the door] in. They were very surprised to see all women in the apartment, but they picked out who [were] the people involved with the Janes and who were the people there for the service,” Avruch said.

The Janes were all arrested and subsequently each charged with 11 counts of abortion and conspiracy to commit abortion, which carried a 10-year sentence per count. As the charges were filed, each Jane had their mugshots taken. Avruch garnered a reputation because of it.

“I apparently had the worst, most smirk-looking smile,” she said. “It was because I kept smiling at the person taking my picture because it’s instinctive to smile in the picture. They really didn’t want me to smile. And they were yelling at me, so I was getting bad. They got to me.”

The Janes spent a long night at the police station and women’s prison. The next morning, they were released on bail and began planning their defense. They decided to find one lawyer to defend all of them, keeping their case together.

“We very much wanted a lawyer who wasn’t interested in breaking political borders. We didn’t necessarily want an attorney who was so excited with the idea that he might be able to argue a case before the Supreme Court that he might lose, and then we [would] go to jail for a long time. This was not our interest. We were very interested in having the case go away,” Avruch said.

They decided on Jo-Anne Wolfson, who had successfully defended some of the Black Panthers in the past. Their saving grace was Roe v. Wade, which was then sitting before the Supreme Court. Wolfson decided that it would be in the Janes’ best interest to wait to see how the Supreme Court ruled.

Wolfson’s strategy was to continuously file standard motions that the prosecution would have to address. “The prosecution never seemed to get around to addressing these motions,” Avruch said. “Everybody was sort of playing this waiting game.”

Eventually, the Supreme Court ruled to legalize abortion on the basis of privacy, resolving the Janes’ case. The prosecution agreed to not charge them with practicing medicine without a license so long as the Janes did not ask for their medical instruments back and begin practicing again.

Between Avruch’s arrest and the decision, she graduated and moved to California, returning to Chicago whenever subpoenaed. “It was a little strange, because after the arrest, I still had papers to write,” Avruch laughed.

After the seven members’ arrests and the ruling of Roe v. Wade, the Janes ultimately disbanded. “Since legal abortion clinics were opening in Chicago at the time, there was no reason to get the instruments back. Jane fulfilled its function and went away,” Avruch recalls. “I think that all of us felt that, ‘okay, well, women now have a right to abortion, so we will go on to other things.’”

1973: The Next Chapter

The Janes fully believed Roe v. Wade marked the end of the organization, and in a way it did; per their agreement with the State Attorney, the Janes stopped organizing and performing abortions. Some Jane-affiliates, such as Diamond, went on to pursue careers related to their work from this era. Diamond works as a clinical psychologist with a focus on fertility counseling.

Diamond’s experience at Jane also influenced her as a mother. “The whole experience of having gone through an illegal abortion and trying to do some good through Jane has been very impactful, especially because I raised two daughters,” she said. “It was one of the most important things for me in being a parent that I raised them in ways that they understood their sexuality and were protected and could enjoy it.”

Given the secretive work of the Janes, many of the members, especially those from the Class of 1972, have remained close to each other. During Alumni Weekend, May 19–22, 2022, the Janes in that graduating class hosted a panel on women’s rights, focusing on the past, present, and future of abortions.

Many of the women continued to support abortion rights after the disbandment of the Janes, donating to organizations like Planned Parenthood and attending pro-choice rallies. However, they acknowledge that their work is far from done.

“I think, very soon, women could have fewer rights than they did in 1971,” Avruch said one month before the 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling.

“This is the most intimate decision of a person’s life, when or whether or with whom we have a child. It’s a fundamental freedom,” Booth said. “Right now, our freedoms are under attack, our reproductive freedom, but also the freedom to vote, the freedom to thrive and prosper for many people. And so we’re really at a knife’s edge in society, between the struggle for freedom and those who want to deny that freedom and create an authoritarian rule.”

A common sentiment shared by the Janes and feminists interviewed by The Maroon was that although the burden now rests on the younger generations, they are not alone.

“I’d like to hear from the younger members of the group, what they think they can be doing at this juncture,” Levine said. “I just want to remind them that local action is what’s going to get things started and effective. There’s no antipathy among collegiate age women now.”

West noted that though the Janes are no longer operational, their work can be resumed.

“I think that it’s potentially something that can be done going forward,” she said.

The work of the Janes not only championed women’s rights in a time when it wasn’t easy or legal but also illuminated the ways that everyday people, regardless of age, can create a lasting impact.

“One of the things that the Janes taught me is that a group of committed people working together can accomplish quite a bit,” Avruch said. “It’s valuable to organize and find like-minded people and join together and be engaged in trying to make the country better.”

Booth echoed this sentiment. “We have to come together. We have to educate, we have to raise the funds, we have to talk to others, we have to recruit people to be involved. We have to show up. To raise our voices, we need to organize. And if we organize with love at the center, we will change this world,” she said. “This will not stand.”

RE Morrow / Apr 25, 2023 at 10:09 am

Great article, but “Our Bodies, Ourselves” is decidedly *not* a “full-length (or any other kind of) novel.” It is a fairly comprehensive manual, guide, resource, and testimonial which provides extensive information on pretty much all things related to women’s bodies, health, and well being.