I never cared for the Reynolds Club much, but that was before they destroyed it.

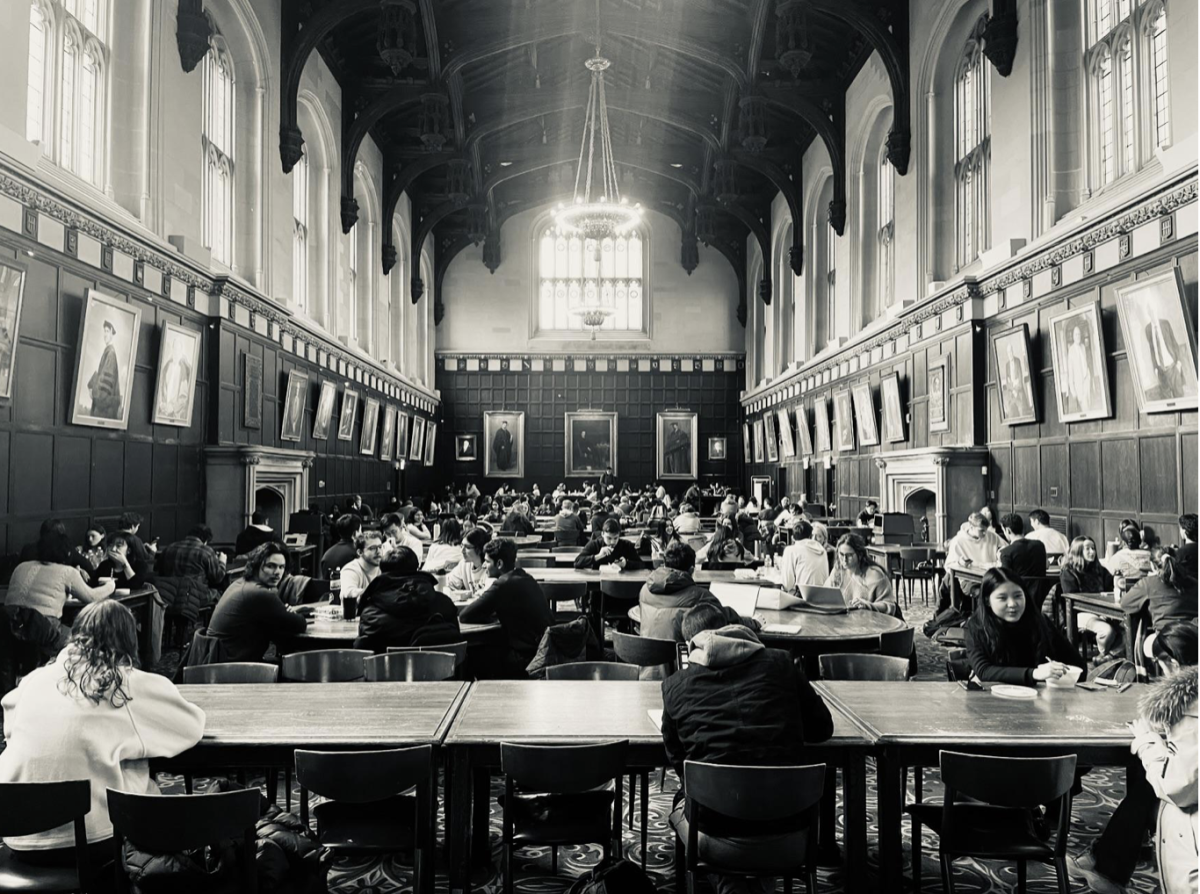

The building is truly Hogwartsian. A pale-brown tower down to the steeple, it is one of the first locations students become acquainted with upon arriving at the University of Chicago in September, bright-eyed and clad in North Face or Carhartt. The building holds a variety of attractions for incomers: a sleek ATM; a student-run café, Hallowed Grounds, frequented by the kinds of well-dressed 20-year-olds who will one day, apologetically, move to Brooklyn; a Pret a Manger, one of two in Chicago (the founder’s son went here); various carpeted quiet-study rooms; and a large dining room, filled with regal portraits of past University presidents, connected to a food court.

This food court, Hutchinson Commons, is synonymous with the Reynolds Club more than any other locale. So much so that some never call it the Reynolds Club. Instead, they refer to it by its food court. They call it Hutch.

During my first year at the University of Chicago, I lived alone in a dorm, had cotton swabs rammed up my nose each week, and washed my snotty cloth masks out every evening in the bathroom sink. I also occasionally made the walk from my dorm to Hutch. Noodle soup, taco bowls; all the collegiate hits were on offer. There were also a few special deals. On Wednesdays, as is often noted in UChicago promotional paraphernalia, students flocked to the building for dollar milkshakes. On Saturday nights, Hutch made certain dishes free to anyone on campus with a meal plan.

My early trips to Hutch were never particularly memorable, although that may have just been the brain fog. In the age of the coronavirus, students weren’t allowed to eat indoors. Instead, we stood under the tepid lamplight of University Avenue, alongside dozens—on Saturday nights, hundreds—of other hungry souls. We filed in, ordered our food at one of the restaurants, and left to eat in circles outside, or else walked back to our dorms, our pad thai cradled snugly in cardboard to-go boxes. It was a dreamy, dreary time.

But that time passed; Biden won, the coronavirus fell out of the collective consciousness, and I moved off-campus and stopped paying $7,500 a year for a meal plan. I bought groceries and cooked, like a real adult, except when I got drunk with my friends. Then we’d order McDonald’s. Or Quesalupas. The Reynolds Club faded into the background of my life. This was how the University was able to undermine it.

Nothing about Hutch changed much over the years. I think the Indian place was swapped out for a different Indian place at some point, but that didn’t cause too much of a stir. But a few weeks into my final year at the college, a bit of poster board caught my eye. Outside the building, a bright-orange advertisement proclaimed the new partnership of Hutch with the food ordering platform Grubhub. Order From Your Phone!, it exclaimed happily.

I had seen the rise of mobile food delivery with my own eyes, particularly in New York City, where I grew up. New York, where cash was once king, became in the 2010s littered with businesses that didn’t accept it. Ads for Seamless, New York’s premier delivery service (and a company Grubhub purchased in 2013), beckoned to residents from subway-car interiors. “Mobile Pick-Up” stations quickly became a prerequisite for any new restaurant, café, or bakery.

I worked in one such bakery once. Two summers back, as a cashier. A large part of my job was checking the company iPads every two minutes for new mobile orders. If there was one, I’d pack the rugelach and olive sticks and babka and whatever else into a bag and staple it closed. A few minutes later, a guy wielding an electric bicycle tracking dirt onto the floor would come into the bakery and show me the name on his phone. It was usually something like “Hillary”. I’d give him the bag, and he’d leave. It was like magic.

This was in 2021, after the pandemic served to further sunder the ties between customer, food, and vendor, and the use of mobile food delivery services had grown exponentially. American restaurants have delivered to people’s homes since Warren Harding was in office—1922 is the first instance of the idea appearing in writing, after a Chinese restaurant, Kin-Chu Café in Los Angeles, cannily popped an advertisement in the Glendale News-Press pledging to “deliver hot dishes direct to you” until 1 a.m.—but post-coronavirus, the idea of food delivery has been taken to its logical, awful extreme. New York City is now forced to reckon with institutions like Gopuff, a consumer goods company worth $15 billion, which claims, on their website, to deliver “groceries, alcohol, home essentials & more” to your door in minutes. This bastion of social anxiety recently opened a storefront on Canal Street in Manhattan, near where I grew up. “We’ll deliver all you need in minutes. Or just come in!” reads the lettering on their window, in what one can only hope is some kind of unfunny satire on the part of a suicidal marketing director. Their membership program is called “The FAM,” which stands for “Fucking Awesome Membership;” their Twitter account posts things such as “Hope ya’ll are thirsty because there’s maaaaad hydration deals in the app this week.” In 2018, Gopuff was found to be recording user interactions on its app and sending the videos to a third-party mobile analytics company without consent. In early 2023, the company was fined $6.2 million by the Massachusetts Attorney General for listing its drivers as “independent contractors,” which allowed for fewer benefits and protections on the part of the employer. (Grubhub continues to claim its drivers are contractors.)

Visions of Gopuff flashed through my mind upon seeing the orange advertisement outside the Reynolds Club. Upon entering Hutch, things looked even worse. More Grubhub ads lined the walls, encircling eaters-to-be. A line of crowd-control stanchions divided the hall lengthwise. On one side of these stanchions, kitchen workers stood behind their counters—cutting onions, frying chicken, chilling poké—and students flitted through the other, picking up their food and leaving without breaking stride. If you were one of the sorry few who didn’t have the Grubhub app on your phone, not to worry. You could place your order from one of four large tablets—“Ultimate Kiosks,” the company calls them—which stood opposite the kitchens. Crossing through the stanchions like water bugs were the kitchen supervisors, whose main job was to hand students their boxed food after it had been placed on a wire rack by the kitchen staff and yell at impatient students who were trying to grab it themselves.

Fuck, I thought.

Hutch was never perfect. The food was expensive, and the portions small. Still, you used to be able to at least acknowledge the service worker toasting your quesadilla. This new structure was intensely, almost comically dystopian; it literally segregated students from workers. Don’t acknowledge the commoners, the space seemed to say. Pick your food up and leave. I ordered from the tablet, waited outside, and picked up my food without a word. The worst part was just how easy it was.

“A lot of it is driven by, I guess, this ever-present drive for convenience.” Emelyn Rude, a food writer and author of Tastes Like Chicken: A History of America’s Favorite Bird, told me over the phone. “My friend is a high school teacher, and she says that basically all of her kids order Starbucks to be delivered at the end of class. Which is highly annoying for the security guards.”

Rude condemned the large cut—sometimes as much as 20 per cent—which intermediaries such as Grubhub take from restaurants. This severely screws up any given restaurant’s day-to-day. “In restaurants the margins are, even if you’re doing good, like 10 per cent,” she said. “You’re killing it as a restaurant if you’re [making] a 10 per cent profit.” This means when an order goes out for delivery, that little off the top going to Gruhhub can be the difference between a place thriving and falling apart. But what are you going to do—not offer delivery? The sea of cyclists is already in motion; you’d be remiss not to join.

The food historian agreed that online food delivery “does create more distance in an already distant system.” She also said that partnering with Grubhub likely “made financial sense for the university.” Food providers are expensive. We ended the call.

Grubhub at Hutch, of course, works a bit differently than Grubhub at a restaurant. It’s mobile pick-up, not mobile delivery, so you still have the massive burden of having to go get the food yourself. Nevertheless, Grubhub co-opting the food court in order to expand their customer base among students makes sense. There’s more than a dash of nepotism in the partnership: the company is Chicago-based, and its cofounder, a man named Matt Maloney, holds a 2010 Masters of Business Administration from UChicago. Grubhub was the winner of the Edward L. Kaplan New Venture Challenge at the UChicago Booth School of Business in 2006. Currently, Maloney is listed as an “advisory board member” for the Booth School.

So Grubhub, after growing out of the university, has slowly stuck its fingers back in as one might stick a finger into a molten vat of cheese fondue. And the university is all too willing to be penetrated like this, because it looks great for them too. A business-school graduate begets a start-up, secures eighty million dollars in venture capital funding, sells it in 2021 to a Dutch company, Just Eat Takeaway, for $7.3 billion, while remaining CEO; and now brings his behemoth back home to roost, all too happy to help modernize the food court he ate at as a zitty 20-something. UChicago earns more prestige, more money. The checks clear.

Now Grubhub is hungry, hungry beyond its volition. It is running itself into the ground in an everlasting desire for more; no longer its own, nor mine, nor yours.

And yet: the reason Grubhub’s acquisition of Hutch is so interesting is because, at the same time, the company kind of needs this. Grubhub laid off 15 per cent of its full-time staff in June 2023, which included around 130 workers in the heart of the Windy City. Their most recent financials, released in January 2024, show a 13 per cent decline in orders and a 15 per cent decline in transaction value from the same period last year. Hell, the company’s been up for sale since 2022!

“We’ve made some difficult decisions,” Just Eat Takeaway’s CEO Jitse Groen (who can be found under the profile URL “pizza” on LinkedIn—how irreverent, how charming!) recently said of Grubhub in an earnings call. “We’re cutting costs over there to make sure that our cash burn in the U.S. goes to zero as rapidly as possible.” And so the company’s takeover of Hutchinson Commons is not simply a partnership to make them a little extra dough. It’s a microcosm of a larger organizational plan that shareholders hope will see Goliath regain his footing. They’ll woo the next generation of consumers in Gen Z. It shouldn’t be too complicated: they love their screens and their convenience, those kids. And after the pandemic, they’re traumatized—they don’t want to talk to anyone. So we install mobile pay-and-go systems at their universities. And we’ll save them time—time that could be spent studying, or TikToking, or whatever it is they like to do.

While it’s difficult to determine when the process of Grubhub-izing the college experience truly began, the strategy has worked well for the company. The company stated in April 2023 that they have set up shop at over 300 different colleges nationwide. Such expansion has bred technological innovation. In 2021, Grubhub trialed the use of campus delivery robots after agreeing a partnership with the Russian company Yandex. They ended this partnership after Russia invaded Ukraine, but have since sent out a second fleet of the little guys in partnership with the Estonian company Starship Technologies, currently in use at colleges such as the University of Kentucky, Southern Methodist University, and Fairfield University. Soon, you won’t even need those pesky independent contractors to deliver your food—it’ll be a cute metal box with blinking lights and wheels.

More recently, Grubhub struck a deal with Amazon for the use of Just Walk Out, an artificial-intelligence powered checkout system wherein shoppers can take what they need from convenience stores and groceries and—get this—just walk out, no pimply cashier required. (just security guards to stop all those lovable rogues from Just Walking Out with $300 of unpaid-for groceries in their arms.) The partnership was trialed at Loyola University Maryland, where one of their campus convenience stores was retrofitted with the tech. “The services and products we provide for our campus partners are designed to enhance and improve the dining experience, and we’re excited to offer this innovative and frictionless technology to our campus partners,” Grubhub’s COO Mike Evans said in a statement. No doubt more universities are mulling over plans to implement such a high-tech pay-and-go system at their overpriced kitchens and convenience stores. It sounds great in a brochure.

You get it by now. In Grubhub’s ideal world, no one orders food by talking to another human. Because, well, why should you? Do you enjoy standing there, in front of someone else, attempting to make small talk or else blinking in musky silence, as this other scoops your couscous or blackens your chicken, both parties all too aware of the class disparities between themselves? So awkward! Why not, then, simply Get Food Now! on your phone? With a tap of a screen, your meal becomes entirely removed from the context surrounding it. A salad, a pizza, becomes a stable, sterile entity, appearing when and where you want it, in full. To view your food as something assembled from base ingredients, by another beating heart—a heart which could use a cigarette, or at least a few minutes in a yellowing break room, a heart which might be thinking about their lover, or about killing themselves, as they dress your bowl, as they add your side order of bread—all this should feel a strange concept.

Look. I am a professional and did not want to vilify Grubhub and the University of Chicago without doing my journalistic diligence. Maybe I was wrong about Hutch. Maybe it was better this way. And besides, even if I couldn’t help feeling appalled when I first laid eyes upon the new Hutch, one man alone can do nothing, except maybe complain. It was only right to take the temperature of the student body, and, more vitally, the workers who cooked their food.

The students were easy. “Yeah, interview me for your article, man. That would be cool. Yeah. Hutch is weird now.” Then a rip from a green apple vape. I liked listening to them speak; their comments were colorful and came from a genuine place of care for the Reynolds Club. A large populus of students, like myself, were saddened by how corporate the place had become, that future generations of students wouldn’t get to talk to the guys at the Middle Eastern place. (I remember those guys. I used to try to be really nice with them, like weirdly polite, so they’d throw me an extra falafel. It worked once or twice.) These gaggles of students encouraged my article, although, in typically jaded fashion, they weren’t hopeful about it inspiring any change.

On the other hand, some students didn’t mind the changes made to Hutch; they liked that they could order everything ahead of time, and that there were fewer lines. Fair points both. This crowd was somewhat self-selecting; first-years visit Hutch more than anyone, and these broken youth didn’t know Hutch without Grubhub. They liked the screens. They were surprised to hear that wasn’t how it had always been.

Next, I tried to speak to the staff. I expected some hesitation on this front. Lord knows an air of enmity exists around workers paid to hang around privileged kids all day, who have to clean their trash and make sure no homeless people enter their sacred learning spaces or whatever. Still, I wasn’t prepared for just how onerous it would be to get the workers to speak about, you know, their workplace. In previous reporting projects, I had spoken to food truck owners, sports coaches, and campus ROTC managers about their jobs. Sometimes people took persuading, but I was always able to convince them I meant no harm. That just wasn’t the case at Hutch.

Let no one say I didn’t try. For weeks on end, I strolled into the Reynolds Club, sometimes tapping a few buttons on an Ultimate Kiosk so as to not look as conspicuous, really just so I could linger around the space (not exactly encouraged these days) for as long as possible and try to finagle an interview. Hi, sorry. I’m trying to write an article. For the student newspaper, about how Hutch has changed in the last six months. Would you be interested in speaking about your experiences working here? Boom. I attacked the supervisors first. They were more accessible, as they flitted around directly across from me on the other side of the stanchions. They were also extremely against the whole interview idea. They told me, flatly and later threateningly, that they wouldn’t speak to reporters. It was in their contracts, or they would have to inform their manager first, or something. No, I wasn’t allowed to ask their manager. I emailed Campus Dining to try to get to a higher-up, but they wouldn’t speak to me in-person. They answered some PR-type questions in writing. Q: Are there any plans to expand the Grubhub partnership to other vendors on campus? A: After holding conversations with students and stakeholders, we will consider expansion to other UChicago Dining Cafés that might benefit from mobile ordering.

These rejections just made me more determined to speak to some semblance of staffer. I began leaning over stanchions while supervisors floated around on the other end of the hall, like a middle-schooler passing notes, trying to convince kitchen-workers to meet me on their breaks, or after their shifts, for an interview. They too were apprehensive. Some refused with a curt shake of a hand; some echoed the same “we’re not meant to speak to reporters” line. And some accepted—which somewhat undercut the idea that they weren’t allowed to speak to me—before failing to show up the day of, or else telling me they had changed their minds later.

I was hurt—maybe I shouldn’t have been, but I was. Did they not like the look on my face, the clothes I was wearing? Did they think I was a privileged dick (and only one of those things is true)? Some supervisors had gotten truly angry. One of them told a friend of mine to tell me to stop coming, that I was making their jobs harder. I understood, but I was sad it had come to this. I wanted to grab an Ultimate Kiosk by its glass sides and stare into its vacuous monitor. Look. I would say. Look what I’ve done because of you.

Mikhail Bulgakov burned his first draft of Master and Margarita after a manic episode. When it was finally published, Russia’s government censured it until long after his death. Herman Melville had to borrow money from friends to set the type of Moby-Dick after his publisher refused an advance. This was the one bright side I could see: like all great stories, a problem had broken out in mine’s telling.

It was a Wednesday night, and I was washing down my sorrows with cider. I was with a friend, Brenda; we were sitting in a booth in UChicago’s oaken campus pub. The place is a real vestige of the past. Weird paintings on the walls. Foosball table. You almost expect to see Philip Roth or Bernie or some other famous alum here, sipping an Old Style and trying to sidle up to a nearby redhead.

I told Brenda, as I had told many others in the past week, about my difficulties interviewing the staff at Hutch. My friend works there, she replied. You could speak to them?

This was news to me. I didn’t realize undergraduates were even allowed to be employed at the food court. Even before the changes, the gap between us and them felt too drastic for such intermingling to ever happen. But I wasn’t one to question fate. This was an in.

This friend of a friend we’ll call Rae. They were a year younger than I was, though they looked older. They had worked in the food court for about 18 months. This quarter, they were there for a few hours during the week, as well as on Saturday nights, covering the influx of patrons. Previous quarters, they said, they had worked much more, but right now they just didn’t have the time.

Rae told me the Grubhub point of sale system was implemented in August. The staff were corralled and told how the orders would now reach them; how instead of a customer verbally asking them for food, text boxes would float to them, quickly and gently, screen to screen. The new system was okay, they said. They liked that they didn’t have to deal with particular kinds of customers anymore. “There are certain people who take forever to order, and they don’t know what’s on the menu, and then they try to convince us to add things,” they told me. But the new technology wasn’t perfect. During one lunch rush, the screens in the kitchens shut off; the workers couldn’t see the orders streaming in. They were still there, of course, piling up on each other in the cloud, whimpering out to be made. But without any tablets, they may as well have not been. During another busy period, the sticky slips that printed out with the customer’s name and which the staff attached to the containers as a kind of receipt ran out. Workers no longer knew which order went where. But now, it seemed they’d worked out all the kinks. The modish system worked well.

I asked Rae if they mourned the loss of interaction between worker and student. “Even though it’s nice to not have to deal with annoying people, it’s also…” They trailed off. “I don’t know if dehumanizing is the word, but we’re so separated. They don’t even let anybody approach us anymore.”

Rae introduced me to a man who worked in the kitchen, who told me he’d rather go unnamed. Well, he told Rae, who was translating from Spanish to English for me. The man was short and stout; the assembler of untold stews and platters. He told Rae the new system crashed sometimes, which slowed things down for the staff. There were also more complex dishes at his station which wouldn’t get ordered as much anymore, because the students weren’t able to look at the food in the real world or ask the server if it was any good. The ingredients, in a sense, didn’t exist anymore. The food was a picture on a phone screen, or it was there, in your hands—no in-between. It was a Magritte painting, or maybe it was a pipe. Me gustaba hablar con los estudiantes que hablaban español. He had made friends with a few regulars. He assumed the change was done to keep up with the technological advances of the world. If I were the owner of Hutch, he said, I would change it back.

I jotted it all down and thanked Rae. I should be happy, I told myself afterwards. I’d gotten words from those whose words I’d wanted most. But I still felt like I was going nowhere fast. What were all these words for? What was I doing here?

Maybe I was being dramatic. At the bakery I worked at, I never minded doing the mobile orders. I didn’t have to add up the cost on the register. I drew Hillary’s name in cursive on her bags when it was slow, just to be nice, and convinced myself she’d appreciate it. There was something sweet, fresh-feeling, about the simplicity and the solitude of it all.

But then, isn’t that exactly what they wanted? To privatize everything, make every step of the process asocial? The promotional tape was full of pretty, blank screens, each one staring upwards, looking for something in your eyes. It sure felt like we were being trained to forget each other. “We are all alone, born alone, die alone,” Hunter S. Thompson mourned. And with every order we drift, a plastic raft, towards that platitude.

A couple months later, another Reynolds Club worker agreed to speak with me. She worked at Pret, it should be said, not Hutch, but I would take what I could get at this point. It was a more spontaneous interview than I had previously attempted. Usually, I asked what day the worker would like to speak, tried to be amenable to their schedules. This time I just ordered a coffee and, tapping my card against the reader, asked if she was interested in speaking about working in the Reynolds Club. “Yeah,” she said. “Now?” Maybe that was why it worked out.

Diana—that’s what I’ll call her— had worked at Pret for three years. A few times a day she wandered over to the food court to talk to her friends, to the mild irritation of her supervisors. But she’d also help out at Hutch when it was busy: jockeying traffic, restocking drinks, and the like. “I’ve enjoyed my three years,” she said. “Coming here, seeing y’all. Helping y’all and just getting to know y’all.”

I asked Diana if she thought students were in favor of the new system. She said no, at least not at first. “They’re used to telling them… how to assemble their food. So when they food is made already, and they just come and grab, they weren’t really into that. They weren’t feeling that at all. Just how we like to interact with the kids, they like to interact with the cooks as well.” I followed up: do the cooks at Hutch like the system? “It’s really like 50/50. Some of them like it, some of them don’t. Some of them want to talk to them, some of them just want their food. It’s 50/50. But it’s all coming along.”

I looked at my phone, where I had pecked out some questions, and I thought about how it really was all coming along. There were no real controversies, no protests. Six months into the Grubhub takeover, and it already felt like it had been there for years.

“Okay,” I said. “Well. Which workers like to talk to the kids?”

“Like Kabob-it,” Diana said, referring to one of the restaurants, “[My coworker], she likes to ask the kids how they doing with they day, how the classes going. Some of them right now be needing somebody to ask them, are they okay. ‘Do you need to talk?’ They be looking for that. Some of the kids be looking for that. It keeps their day going.”

I have to admit something, and it is this: working at the New York City bakery was the most deranged time of my life. My then-girlfriend and I were breaking up that August. She was going back to college in Boston; I would remain in New York until UChicago started up in late September. We couldn’t do long-distance. We had tried before (we would try again), but it had always turned out pretty awful. So, we were breaking up.

Before her lovely exodus, I tried to see her as much as I could. And it was terrible: I’d wake up, a cough slipping down my throat, at five in the morning for the early shift. Watch the rats skitter across the subway tracks, hot and wet with summer. I’d work until two—nice to have half the day left, but I was always exhausted and dizzy and sad, no matter how brightly the sun shone or how much pastry I’d swallowed.

Talking to the customers in the bakery granted me some reprieve. I got to know regulars, ask people how they were holding up, because Lord knows I wasn’t. The variety of faces I saw each day was astonishing—you don’t know just how many noses exist in the world until you’ve worked service. I’d play morality games with them, sometimes—give them the bigger cookie if they were polite, the runt of the litter if they didn’t tip, that sort of thing. Did that make me a bad person? Maybe. But I was depressed, and one of the only good things about being that way is that you have an excuse to do things like that.

I worked until mid-September, torturing myself with lack of sleep, with the humid subway system, with thinking about her. What was she up to these days? She had a septum piercing now—I saw it in a photo she posted. I cried on the closing shift a few times, usually at around 9 o’clock, when I’d go outside and Windex the metallic dining tables. I wasn’t happy; for all the kindness of my co-workers, and all the allure of strangers, my mental health was bad, and I was relieved to return to Chicago.

I was privileged too; I could afford to leave, to busy myself with school. My fellow cashiers—How’s it going, guys?—Tino, Nikkol, and Sanjid, each worked part-time while they took classes. Others were working as much as they could as they saved up to go do other things. One of the managers, Martin, was trying to go into theater; he’s in L.A. now, still trying. Justin moved to a different bakery. Rocco quit. There was a Japanese guy whose name was Gane. I got it wrong about four separate times before I figured out it was pronounced “gain.” One morning, I saw him in the back, putting the finishing touches on a rack of croissants. He proudly told me he’d worked the first-ever overnight shift in the bakery’s history. I couldn’t even imagine. “Coffee,” he explained happily.

Every service worker must deal with their 9-to-5 or 6-to-2 or (God forbid) 10 p.m.-to-6 a.m. while the world spins awfully and forcefully around them. There’s no free time, save the weekends; you end up calling in sick quite a bit, skirting around the real issue. Things are less than ideal.

The only thing that can save us is human interaction, and it is human interaction that Grubhub yearns to do away with. With more isolated convenience we consume more efficiently. It’s far easier to turn the lonely into data points. I’m not saying striking up a rapport with every kebab guy you meet isn’t also transactional. There will always be a worker and a consumer; to feel more virtuous than those who only use Walmart self-checkout just because you know Ahmed or Tony or Esteban’s name behind the counter at the local bodega isn’t the point. But a bit of understanding between warm bodies might make us all feel a bit better.

I’m not sure where Rae or the man she introduced me to has gone; I haven’t seen them around the university for a long time. I never got to speak with Diana’s coworker, either. But I will occasionally run into Diana when I stroll into the Reynolds Club. On those occasions, I think back to the time she made time for me, when she told her co-worker to cover and led me into a table inside Hutchinson Commons and spoke to me about her life. I was paranoid, at the time, sitting in the familiar brown dining room spackled with portraits of past University presidents. I hoped no one would overhear us. It wasn’t a rational fear, I know, but the supervisors had been so angry with me—they surely wouldn’t like the look of this covert interview. The wrath of it all hung over me like a chandelier.

We were just talking, I realize now.

Editor’s note: Grey City, the Maroon’s longform, features section publishes a mix of personal opinion and reported writing. The views expressed in this piece are those of the authors and are not reflective of the Maroon or Grey City. Names of University employees have been changed in the piece to respect the sources’ requests for anonymity.

henry / May 17, 2024 at 8:24 pm

Fun fact, the giant tablets are literally just running android. You can open a new tab and browse wikipedia or whatever.

Will Hartnett / May 15, 2024 at 5:53 pm

Brilliant piece. Thoughtful, compelling, so well written. Congratulations

Random Dog / May 14, 2024 at 9:54 pm

BARK! BARK!